New research on killer bees generating some buzz

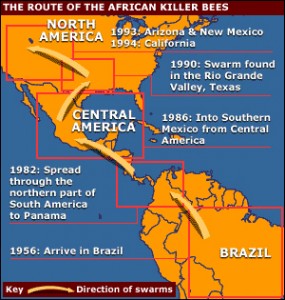

In 1957, a replacement beekeeper accidentally released 26 aggressive Tanzanian queen bees (A. m. scutellata) near Rio Claro, São Paulo State in the southeast of Brazil from hives operated by biologist Warwick Kerr, who had interbred honey bees from Europe and southern Africa. Kerr was attempting to breed a strain of bees that would be better adapted to tropical conditions than the European bees used in South America and southern North America.

Africanized honeybees, or so-called "killer bees," are more aggressive than species native to North and South America.

The African queen bees mated with native drones and the Africanized “killer bees” spread northward. Scientists feared that dangerous swarms of Africanized bees would compete with native bees, which play an important role as pollinators. David Roubik, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, took on the daunting task of sorting out the role of the invading pollinators in tropical forests. In 1988, he set up bee traps in Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve—a vast area of mature tropical rainforest in Quintana Roo state on the Mexican Yucatan—with Rogel Villanueva-Gutiérrez, professor at the Colegio de la Frontera del Sur in Mexico. Africanized bees arrived there in 1989. His 17-year study revealed that Africanized bees caused less damage to native bees than changes in the weather and may even have increased the availability of their food plants.

“Our long view of the invasion shows that bees maintain higher-order evolutionary relationships with plants despite ups and downs in bee species within families,” Roubik explains. “Evolutionary relationships between bees and flowers, along with their flowering schedules, may be the fundamental currency that maintains this community.”

Pollen from each plant species has a unique shape. Researchers compared pollen on bees in traps to pollen from flowers in the forest to determine which plants the bees were visiting.

Over the course of the nearly two-decade study, a severe drought and three hurricanes devastated native bees, but their populations rebounded each time. Africanized bees took over pollination of two plant families that had been important food sources for native bees: the cashew family and the spurge family. However, Pouteria, one of the plants native bees prefer, became more common. A few rare species of bees disappeared from traps later in the study.

Roubik cautions that native populations in less diverse areas might be less resilient to invasions. “Basically we’re seeing ‘scramble competition’ as bees replace a lost source of pollen with pollen from a related plant species that has a similar flowering peak—in less-biodiverse, unprotected areas, bees would not have the same range of options to turn to.”

Posted: 7 October 2009

-

Categories:

News & Announcements , Science and Nature , Tropical Research Institute