On the road in Antarctica: The Secretary’s travel journal

(Scroll down to read earlier entries.)

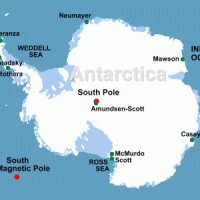

Jan. 20, 2010, The South Pole

Rising early at around 5 a.m., I get moving and go outside to walk off the sleep. Before me lies a different and beautiful world. It is crisp, the air tingles on the skin and the sun, which is not rising because it did not set, is low on the horizon, emanating a rose-tinted light that falls gently on a white landscape. Across McMurdo Sound the mountains rise mute and serene. Mount Erebus looms behind me with its white cloak of snow and ice disguising the seething magmatic heat that lies within. In this seemingly quiet and motionless setting, it is hard to believe that the earth and its covering of ice are on the move.

In this photo of a pressure ridge, the blue underside of a slab of sea ice protrudes up through the surrounding ice. Shifting annual sea ice, pushing against the permanent Ross Ice Shelf, creates pressure ridges of uplifted ice. (Photo by Steven Profaizer, National Science Foundation)

Slowly and almost imperceptibly, the sea ice moves in different directions depending on how close to shore it lies and which current is dominant. At this time of year, sea ice can be thin and often breaks into thousands of pieces that move along together like cattle on a drive. The great ice sheets lying on the continent are thicker and move at their own pace on a course dictated by topography and gravity. While this movement is imperceptible to us, it can be detected in the form of impressive pressure ridges that snake across the ice of the Sound where the plates have come together in a contest of wills. The forces between the ice sheets are enormous and result in buckling at the edges that form pressure ridges with ice piled tens of feet high. These ridges create openings in the ice that Stellars seals use to surface in order to sun themselves and rest from a day’s fishing. Dozens of these creatures can be seen in groups on the ice as I survey the scene. Humans are newcomers to this part of the world, and of the species who live here we are the least adapted and the least attuned to the ways of it.

After a hearty breakfast, I check e-mail to make sure yesterday’s journal, finished late last night, made it to the Castle. The answer—mostly. Seems I tried to send too many pictures at once and they did not get through. Panic! I have 15 minutes to rectify this before we leave to board the plane. I go to work on a computer that seems agonizingly slow. “Come on, come on, read the dadgum file!” (I actually said something a little more earthy.) Finally, the system absorbs the last picture and I rush to put on the final layer of the cold gear for the trip to the South Pole.

We are driven back to the Pegasus Airport and board a Hercules C130 that is even more spartan than the C17 we flew in on. The Hercules, the workhorse for the Air Force around the world, is a marvelous airplane that can land and take off on short runways in difficult conditions. Ours is outfitted with skis so it can slalom along on the ice to take off. I visit with the pilots in the cockpit after we are off the ground and they are reassuring by virtue of their confidence and professionalism. These are the men and women of the New York National Guard who have been at this job for many years. They understand how to navigate in a part of the world where latitude and longitude are almost meaningless because they all converge at the Pole. So they invent their own grid to help guide them assisted by GPS technology.

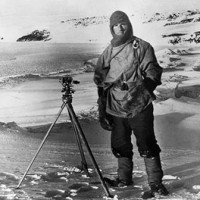

Flying at 25,000 feet we can see the massive ice sheets and glaciers below us as well as the upper reaches of mountains that are high enough to rise out of the thousands of feet of ice that are found here. We are following largely a north-by-northwest route from McMurdo to the Pole, roughly paralleling the route that Scott used on his ill-fated run to the Pole. Scott, the hardnosed British soldier, had his team pull their own sleds without the help of dogs, foot by agonizing foot over crevasses and pressure ridges on the glaciers. I am amazed as I look down on the Beardmore Glacier—the largest in the world—and its infinite crevasse field. When one considers that Scott was also determined to take along scientific collections, including rocks, it is impressive that Scott got as far as he did. Unfortunately for Scott, however, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen reached the Pole before him using skills he had learned from native people in the Arctic.

One is struck by the fact that the world’s largest glaciers exist in a land where there is so little precipitation. The glaciers have been created over eons, growing little by little each year because that “little by little” never melts. Finally, they grow so massive that gravity eases the weight of the ice downhill through valleys that the glaciers carve wider by bulldozing rock and scraping and gouging it from the mountains. The detritus of the rock grinding is seen at the edges of the glaciers as dark bands.

Our Hercules lands us at the South Pole Station around 11:30 a.m. At the Pole the horizon is flat and the sun simply orbits in a circle around a line drawn straight up from the Pole. Fortunately for us, the weather is good. Although it is 25 below it is not unpleasant because of the lack of wind. We walk to the headquarters facility and in doing so have to walk up three flights of stairs. Remember the warning we were given about the altitude? Although I took the altitude sickness pills we were issued in Christchurch, climbing the stairs I can feel the muscles pull deeply and the air seems too thin.

The facilities at the station are relatively new and built to serve the science and the people who conduct it. About 250 people are here in the summer, which ends three weeks from now in Antarctica. Only a skeleton crew will remain through the long, dark winter to maintain the scientific equipment and facilities infrastructure. In the main conference room of the large headquarters building we are given an overview of the science at the station and its support systems. A few questions elicit some interesting answers. For example, the buildings at the Pole rest on a huge ice sheet that is moving at an estimated speed of 30 feet per year. Each year the buildings travel along for the ride and shift to new locations. The water we are drinking tastes wonderful and we learn that is melt water from ice far below the ground that was formed perhaps 2,500 years ago.

Our plan is to take a tour of most of the many impressive facilities at the Pole. But as we step outside it is all too apparent the weather has turned with a hard wind blowing and ice crystals falling from low clouds. Finally it seems cold enough to make you feel like you are really at the South Pole. I am told that with the wind chill, it feels like 35 degrees below zero—now that’s more like it! It also is exciting to see what is termed a “sun dog”—a beam of light that partially or fully rings the faint sun obscured by the clouds. Our sun dog is a complete halo around the sun and adds an element of beauty to an otherwise gray sky. The turning weather speeds up our tour since it seems the winds and blowing ice dictate that the last plane which was to have flown up from McMurdo is unlikely to make it and we will return on one that has recently arrived.

Our first stop is a telescope that records evidence of the “big bang” and may provide clues as to the cause of it. The team working on this new device is from the University of Chicago under the direction of Dr. John Carlson who explains why the telescope is located at the Pole—conditions are the driest on earth and the telescope can look straight up at the sky with no curvature of the earth involved. Smithsonian scientists are involved with a number of other astronomical devices in the area and I ran into one of our colleagues from the Harvard/Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Harvard Professor John Kovac. We turn to a project called “Ice Cube,” whose principal investigator is Dr. Francis Halzen of the University of Wisconsin. Holes are being drilled a mile and a half into the ice sheet to house instruments that will detect the signature of neutrinos that stray from space into our atmosphere and onto the earth’s surface, particularly in the Antarctic where they strike ice and give off a ghostly glow. These tiny messengers from millions of miles away carry information about the formation of the universe. There are to be 80 vertical strings of some 4,800 detection modules, with most of these already complete. We watch as the last instruments of the season are lowered into the deep hole in the ice and are given the opportunity to autograph a detector’s protective shield. Dr. Halzen informs us these detectors may be in the ice for hundreds of years!

It is impressive not only to see the science of the South Pole but also to meet the people who work here and are rightfully proud of their contributions. Nothing is easy at the Pole, and everything has to be flown in. Equipment and buildings must be assembled and operated in incredibly cold conditions. It is about as difficult as it gets.

Our last stop of the day is at the South Pole itself, which is located near the headquarters building. Flags fly and there are plaques dedicated to Amundsen and Scott and their teams. We take some pictures but it has gotten even colder so no time is lost before we board the return flight to McMurdo and are on our way to base camp. Receding behind us is one of the most unique places in the world and I am glad to have lived to visit it.

Kristina Johnson and Wayne Clough hoist the Smithsonian flag atop Observation Point. Mount Erebus can be seen in the background.

Upon our return at about 6:30 p.m. we have some free time. The temperature is milder at McMurdo and the bright sun energizes me to climb to the top of Observation Point looking out over McMurdo Sound and the station. Members of Scott’s expedition team who remained at base camp would look for his return from the Pole from this point and it is capped by a wooden cross to commemorate Scott and the others who never returned. Kristina Johnson and I climb to the top for the panoramic view that is stunning at this time of day. To commemorate our climb, I have brought along a Smithsonian flag which we fly briefly at the summit. A fitting end for a wonderful day.

________________________________

Jan.19, 2010, McMurdo Station, Antarctica

At 8:30 a.m. we board a large Air Force C-17 cargo plane with about 60 other people bound for the Antarctic and find ourselves in a cavernous aircraft designed for utility rather than creature comfort. Much of the space in the plane is given over to a mountain of equipment and gear with the passengers fitting around it.

Preparing to depart from New Zealand, from left, Tom Peterson, National Science Foundation; Steve Koonin, Department of Energy; Kristina Johnson, DOE; Wayne Clough; Ardent Bement, NSF; and Karl Erb, NSF.

We take off promptly at 9 a.m. for the five-hour flight and we are hopeful of landing at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. There’s always a chance of a “boomerang” flight, where we are forced to return to New Zealand because of poor visibility at McMurdo, but for now we are optimistic.

The Smithsonian and the Antarctic have a surprisingly intertwined history. The first confirmed sightings of the planet’s fifth-largest continent didn’t occur until 1820. In 1828, Congress voted to authorize the United States Exploring Expedition, conducted by the U.S. Navy under the command of then-Lt. Charles Wilkes. From 1838 to 1842, the “Wilkes Expedition” undertook the mapping of uncharted waters and territories of interest to the United States and collected natural specimens. The route of the expedition would take it to the Antarctic where it would attempt to map the outline of the land mass. The expedition was successful and was the first to show that Antarctica is a continent.

Portrait of Captain Charles Wilkes circa 1843 by Thomas Sully. (Courtesy of the U.S. Naval Academy Museum)

The Wilkes Expedition played a major role in development of 19th-century science, particularly in the growth of the U.S. scientific establishment. Many of the species and other items found by the expedition helped form the basis of collections at the brand-new Smithsonian Institution in 1846. A staggering number of specimens was collected during the expedition, including more than 60,000 plants, birds and sea creatures. Scientists still use these collections and now are able to explore new dimensions of them using DNA technology. This past fall, a visiting scientist at the Smithsonian indentified a new species of king crab from the collection, a finding that speaks to the value of collections, and of holding them.Since the Wilkes Expedition, the Smithsonian has supported and benefitted from many more Antarctic expeditions, such as the Ronne expedition supported by Secretary Wetmore.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the Smithsonian continues to have a presence in the Antarctic. Our astronomers are involved in the astrophysical work that takes place at South Pole Telescope, and the Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope and Remote Observatory was operated by the Smithsonian for some 15 years. The National Museum of Natural History houses the U.S. Antarctic Program Invertebrate Collections, which currently number 19 million specimens. Natural History is also home to the U.S. Antarctic Meteorite Program with a collection of more than 12,000 meteorite specimens from the Antarctic. We also manage the U.S. Antarctic Diving Program from the Office of the Under Secretary of Science in collaboration with the National Science Foundation. (I was offered a chance to dive under the ice on this trip, but I declined since I would have had to shave my beard. It’s been with me since 1977 and I’m rather attached to it.)

Fast forward to the 21st century and the Smithsonian continues to have a presence in the Antarctic. Our astronomers are involved in the astrophysical work that takes place at South Pole Telescope, and the Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope and Remote Observatory was operated by the Smithsonian for some 15 years. The National Museum of Natural History houses the U.S. Antarctic Program Invertebrate Collections, which currently number 19 million specimens. Natural History is also home to the U.S. Antarctic Meteorite Program with a collection of more than 12,000 meteorite specimens from the Antarctic. We also manage the U.S. Antarctic Diving Program from the Office of the Under Secretary of Science in collaboration with the National Science Foundation. (I was offered a chance to dive under the ice on this trip, but I declined since I would have had to shave my beard. It’s been with me since 1977 and I’m rather attached to it.)

In addition to the science of the Antarctic, the Smithsonian is engaged in the work of renegotiating the historic Antarctic Treaty. As noted earlier, this important international effort, which involves both scientists and diplomats, began with a symposium at the Smithsonian last fall.

Our flight to McMurdo turns out to be without problem. In fact, the weather is clear and sunny on arrival and the views are spectacular. General Gary North, the commander of the Pacific theater for the Air Force, is on our flight and he graciously invites me to sit in the cockpit with the pilots during the approach to landing at Pegasus airport, which serves McMurdo Station and Scott Station, the New Zealand Antarctic base. The pilot notes that a sunny day here is unusual and that this is one of the most beautiful he has seen. Below lies the jigsaw puzzle of broken sea ice and glistening icebergs sailing in splendid isolation in the dark waters of McMurdo Sound. The horizon is everywhere—a white landscape rising to majestic mountain ridges. In the distance is Mount Erebus, an active volcano whose 12,000-foot peak is set off with drifting plumes of smoke rising from the molten magma that lies inside the crater. As we approach Pegasus airport we see an icebreaker working below to clear a pathway through the sea ice that blocks the way to the port. This activity is critical since the once-a-year arrival of the supply ship is only a few days away.

The C-17 smoothly loses elevation as we target the Pegasus runway—a cleared area on the continental ice sheet near McMurdo Station. A large party meets the plane to remove the supplies and greet us, while another group of warmly clad passengers awaits to board the plane for the return flight to Christchurch. The air is crisp, the sun is bright and the temperature is about 30 F. On our ride from the airport to McMurdo Station we see four Emperor Penguins standing together near the ice road as if they are waiting for someone to drop by and pick them up. As we approach them for a better look we are told that when they are molting, the penguins often just stop and wait for the process to occur.

Capt. Robert Falcon Scott, R.N., prepares to make a scientific measurement on his 1911-1912 Antarctic expedition. (Corbis photo)

We arrive at McMurdo Station, having passed Scott Station on our way, at about 3 p.m. Our accommodations are not opulent by any means, but are welcome. From our location we can see the peak of Observation Point where lookouts were placed to watch for the return of Robert Scott and his four-man team from their race to the South Pole in 1912. Scott and his team never did return, but perished from a combination of exhaustion, hunger and extreme cold.

McMurdo Station itself, now home to some 250 people and supporting many more at the South Pole and Palmer Station and in other areas of the Antarctic, is not designed to esthetically impress, but rather to make the work of the science teams successful. There is an urgency to this effort since the time for research is short given the onset of winter.

Dinner is taken at the commissary with the many and varied constituencies who work at the station. Later an elegant reception is held for the new arrivals. NSF is kind enough to recognize the Smithsonian with a beautiful medal showing Antarctica on one side and an inscription on the other, “The Antarctic is the only continent where science serves as the principal expression of national policy and interest,” a quote issued by the White House in 1970.

As I leave the reception and begin the walk to our residence, I am reminded I am in the Antarctic, not only by the stunning setting, but also by the sun, which at 9 p.m. is still high in the sky and will not set at all tonight. Tomorrow we will don our full cold gear for an early flight to the South Pole where it is estimated the temperature will be around 30 below. We have a full round of activities slated for us and will only arrive back in McMurdo at 8 p.m. unless we are detained by weather—always a threat in this dynamic climate. I look forward with anticipation to another memorable day.

_________________________

Jan. 15- Jan. 18, 2010, Christchurch, New Zealand

It is not often in life you get a second chance. We’ve all turned down opportunities at some time in our lives, only to find that they are never offered again. One of my own regrets has been once missing out on a chance to take a trip to the Antarctic because of other commitments. So last fall, when I was offered a second chance to go to the Antarctic with a small group of scientists and engineers, I jumped at the opportunity! And this time I have even more justification because of the Smithsonian’s long and distinguished history of involvement with the science of the Antarctic.

Getting to this majestic continent today is a lot easier than it was for the great British sea explorer, Captain James Cook, who in 1773 became one of the first explorers to cross the Antarctic circle, opening the way for the many who would follow. His voyage took three years, and it still takes a bit of an effort to get to the Antarctic today. I left Washington, D.C., on Friday, Jan.15, and didn’t arrive in Christchurch, New Zealand until more than 24 hours later.

Christchurch is the home of the United States/New Zealand polar logistics center and is the jumping-off point for the flight to Antarctica. Flying to New Zealand, you pass over the International Dateline, and in the blink of an eye, lose a day of your life. So, we arrived in Christchurch on Sunday, having lost Saturday altogether. The good news is that you get a day back on the return trip. I don’t think I’ll get back that particular Saturday, but it’s still comforting to know I’ll wind up even-steven.

Christchurch is the home of the United States/New Zealand polar logistics center and is the jumping-off point for the flight to Antarctica. Flying to New Zealand, you pass over the International Dateline, and in the blink of an eye, lose a day of your life. So, we arrived in Christchurch on Sunday, having lost Saturday altogether. The good news is that you get a day back on the return trip. I don’t think I’ll get back that particular Saturday, but it’s still comforting to know I’ll wind up even-steven.

Our group of travelers includes our host, Dr. Arden Bement, director of the National Science Foundation; Dr. Tom Peterson, assistant director for engineering, NSF; Dr. Karl Erb, director of the Office of Polar Programs, NSF; Dr. Kristina Johnson, Under Secretary of Energy, Department of Energy; and Dr. Steve Koonin, Under Secretary for Science, DOE. The NSF is responsible for funding and managing U.S. research activities in Antarctica. Its role is essential as an “honest broker” in funding a large number of peer-reviewed programs each year and coordinating the Antarctic research of other entities, including the Smithsonian. I am fortunate to serve as a member of the National Science Board, the governing board for NSF.

Other U.S. government agencies are involved in the Antarctic as well. The Defense Department provides logistics for this challenging area of the world, including all flights to and from the continent and the single annual visit made to McMurdo Station by a supply ship. The Department of Transportation is responsible for providing ice breakers to lead in the supply ship and to assist other research vessels as needed. Finally, the State Department formulates U.S. foreign policy for all of the programs in the Antarctic. This policy conforms to the remarkable Antarctic Treaty, which has been signed by 43 nations, agreeing to avoid militarization or commercialization of the Antarctic. The treaty, first ratified by 12 nations in December 1959, was to be in effect for 50 years and then reconsidered. The reconsideration process was kicked off by a meeting at the Smithsonian last fall where I was privileged to introduce Prince Albert of Monaco, who has developed a strong personal interest in preserving the Antarctic for future generations.

After arriving in Christchurch on Sunday, I spend most of the day resting and reading up on the Antarctic. The Smithsonian has a geographic connection to the Antarctic through the Wetmore Glacier, named after SI’s sixth Secretary Alexander Wetmore, who served from 1944 to 1952. Although Secretary Wetmore himself never visited the Antarctic, he supported and facilitated expeditions there, including one by polar explorer Finne Ronne conducted in 1947 and 1948. During the expedition, Ronne discovered a new glacier and named it for his friend, Secretary Wetmore. I feel very privileged to be the first Secretary to visit the continent and look forward to the continuation of my journey.

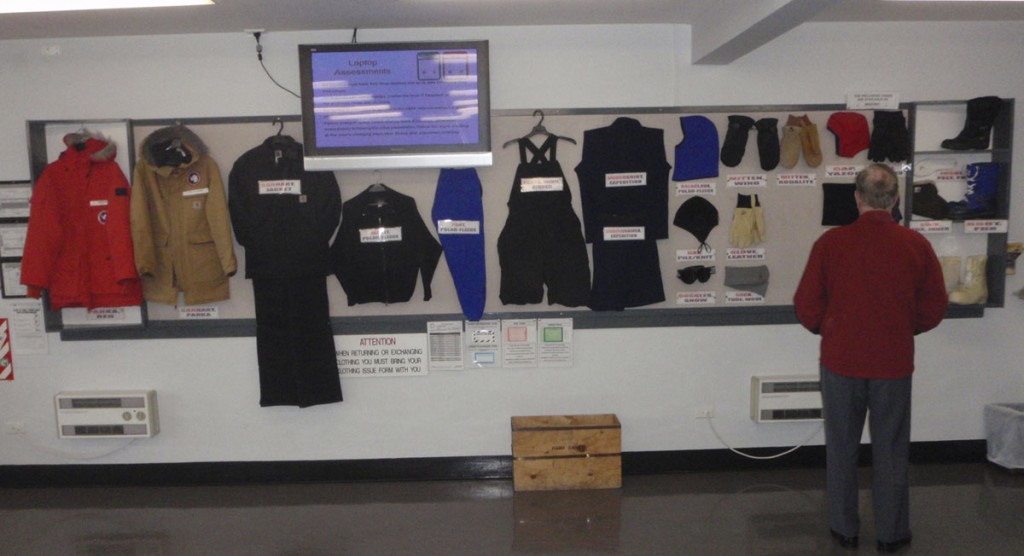

Our second day in Christchurch requires us to spend time at the International Antarctic Centre near the airport. Here, we are outfitted with cold-weather gear and given instructions about safety. For example, it is important to be careful when using a camera in extreme cold because your fingers can freeze to the metal parts of the camera. Just the thought of that happening is certainly an attention-getter. We are advised to take altitude sickness pills because, although the South Pole is only about 7,000 feet in elevation, it will feel like as if we’re at 10,000 feet. The cold-weather gear the Centre outfits us with is an entirely different level of protection than one would normally think about for skiing or other winter activities. There are long johns and then there are extreme long johns. By the time you’re bundled up in all the layers and a big jacket, it’s hard work just to see your feet. This is all serious business and I listen carefully. These folks know what they are talking about and I have no experience with anything as cold as I will experience on this trip.

We are given two large orange duffle bags for our gear and any clothes we will take with us. Since this is Antarctica’s summer, the temperature at McMurdo Station will be only a bit below freezing, and when in camp, we can wear our regular clothes with some precautions.

Wayne Clough (left) and some friends from the education center at the International Antarctic Centre in Christchurch.

After we are outfitted, we take some time to visit the museum and education center at Centre. This is a popular venue for school children where they can learn about the Antarctic from excellent exhibitions and live displays of penguins. The place is packed with children and their families. There is even a cold room where visitors can don special clothes and get a feel for conditions at a place like McMurdo, including blowing snow. The children love this and it is truly educational.

The remainder of the day is spent reviewing materials for the trip and packing our duffels. Rise and shine around 5:30 a.m. for the five-hour flight tomorrow morning. Exciting!

Here are a few facts about the unique place I will be seeing tomorrow for the first time:

• The Antarctic is the coldest, windiest and driest place on the face of the earth. Temperatures average 70 F below zero and have plunged as low as -129 F. Less than two inches of precipitation falls on the Antarctic and in the Dry Valleys, no rain has fallen for 2 million years.

• The continent is the fifth largest of the seven continents of the world and is larger than the United States and Mexico combined.

• All but 2.4 percent of the continent of Antarctica is covered by an ice sheet that averages more than a mile in thickness and in some places reaches three miles thick. The ice sheets contain up to 70 percent of the world’s fresh water.

• If the ice sheets were to melt, sea level would rise more than 200 feet around the globe and Antarctica itself be elevated more than 500 feet because of the relief from the weight of the ice.

• There are no trees in Antarctica and the largest terrestrial animal is the wingless midge (Belgica antarctica), a tiny fly less than one-half of an inch long.

• The Antarctic continent itself was not sighted until 1821 and the first man to reach the South Pole was Roald Admundsen, a Norwegian explorer, in 1911.

• Here’s a good one. The Antarctic was not always cold. Some 200 million years ago, the land masses that were to become South America, Africa and the Antarctic were linked as Gondwanaland, a southern supercontinent that eventually split up. The part of Gondwanaland that was to become part of Antarctica was warm and tropical plants and animals flourished. Assembling the Antarctic into a separate continent was the work of millions of years of plate tectonics and plate movements. The eastern part of the present continent is much older than the western part, with the two separated by the Transantarctic Mountains.

• The Antarctic as we know it today is about 20 million years old at which time it became completely surrounded by the sea. The Antarctic, a continent surrounded by water, differs from the northern Arctic, which is floating ice surrounded by land.

• And, I saved the best for last: According to the International Antarctic Centre, hair grows at twice the rate in the Antarctic as it does elsewhere on the planet.

Posted: 20 January 2010

- Categories:

This was very interesting, I was amazed to find so much that the Smithsonian has accomplished. To read about this was very exciting and I was very interested to see the many places around the world that the Smithsonian has. I would love to someday have the opertunity to visit the Smithsonian in another country. My hat is off to Mr. Clough and his many accomplishments

Wonderful article – I was interested because we just returned from a trip to Chile and was offered the chance to go to the Antarctic – the amount of clothing they said was required discouraged me and I did not go – after reading your article, I am sorry, and as you said, I am sure there will not be a second chance.

AM