The Natural History Museum celebrates 100 years

(This is an edited version of a story first written by Tom Harney in celebration of the Natural History Museum’s 75th anniversary. Don’t miss the slideshow of historic pictures at the end.)

The new building across from the Smithsonian Castle was huge and impressive—two blocks long, covering nearly four acres. Among Washington, D.C. structures in 1910, it was second in size only to the great-domed U.S. Capitol.

Construction had been delayed again and again by slow shipments of granite from quarries in Vermont, Massachusetts and North Carolina. And when the new museum finally and officially opened on March 17, 1910, its cement floors and plaster walls were barely dry.

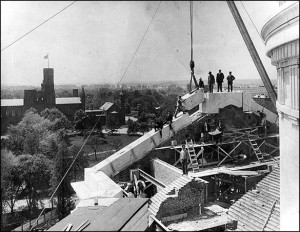

On May 11, 1909, workers set the final stone on the National Museum of Natural History building. Construction of the museum began in 1904, and the granite structure was completed in 1911. The background of this photo shows the first Smithsonian Institution building, known as "the Castle."

The laborious work of installing science exhibits in the Smithsonian’s new Natural History Building had just begun. Only some Indian artifacts and other ethnological exhibits were ready when some 1,600 curious guests made their way through its bronze doors. The star attraction was the Smithsonian’s art collection, installed in one of the building’s central galleries where it was to remain for almost 60 years.

Not a bad opening-day crowd for 1910. But it was just the beginning. Since that day, some 290 million people have visited the building, and the National Museum of Natural History has become one of the world’s most popular museums.

The Paleontology Hall (or Dinosaur Hall) in the National Museum of Natural History, ca. 1932. At the time of this picture the exhibit was called the "Hall of Extinct Monsters."

Years before the Natural History Museum opened in 1910, the Smithsonian had been appealing for funds to house its scientific collections. The Smithsonian’s first U.S. National Museum Building (now the Arts and Industries Building) simply could not accommodate the influx of new artifacts.

A great shell

In 1903, Congress appropriated $3,500,000 for the new building. A design was rapidly developed incorporating the latest advances in museum construction in Europe and America. Samuel Pierpont Langley, third secretary of the Smithsonian, turned the first spadeful of earth in June 1904, and mule-drawn steam shovels began excavating an immense foundation hole on the north side of what was to become the National Mall.

To accommodate exhibitions, the building was planned as a great shell. Three-story-high halls, roofed with enormous skylights and flanked by a series of lower-ceilinged exhibition halls, radiated from the central four-story-high rotunda. On the building’s upper floors were laboratories, offices and large attics—soon to be crammed from floor to ceiling with study collections. The building had two large interior courtyards, designed to provide sunlight and ventilation at a time when electric lights were dim and fans were the only weapon against the suffocating summer heat.

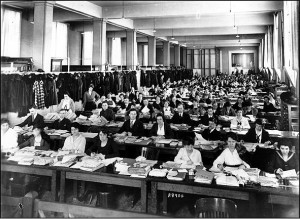

World War I closed the National Museum of Natural History in 1918. Space was needed for 3,000 clerks from the Bureau of War Risk Insurance. The museum reopened in less than a year.

Moving the collections into the building and then creating exhibits were massive tasks consuming years. Archaeologist Neil Judd later recalled working to fill 216 cases with Indian artifacts—some of which had been in storage since they came to the Smithsonian in 1876. He was told to hurry and had no time to mark and describe the individual specimens or even dust them.

The museum quickly became popular with the public, drawing some 50,000 visitors in its first nine months. The following year, the Smithsonian opened the museum for half a day on Sunday; in that era of the six-day workweek, this experiment gave men and women in the nation’s capital their first opportunity to spend a leisurely afternoon at a museum.

A research center

From the very beginning, the museum was research oriented. In 1910-1911, the Smithsonian reported that the Natural History Museum had men and women in the field investigating the antiquity of man in South America, collecting mollusks and other marine invertebrates in the Gulf of California, conducting a biological survey of the Panama Canal Zone, studying the geology of the Petrified Forest of Arizona and surveying bird life in the Aleutian Islands.

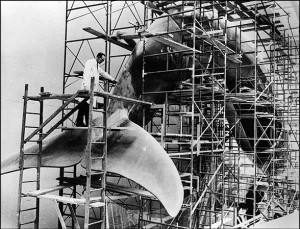

Taxidermist/modeller John Widener works on the cast model of the giant whale featured in the Life in the Sea exhibit in the National Museum of Natural History, ca. 1950's.

Working closely with the museum, scientists from other U.S. government agencies—the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce and Interior—added plants, insects, fish, mammals, amphibians and reptiles and rocks and fossils to the collections, contributing to the museum’s strength as a research center.

Collections that poured into the museum also provided dramatic new exhibits to fill the huge exhibition halls. In 1923, paleontological curator Charles W. Gilmore led a field party to Utah to excavate the gigantic bones of a Diplodocus dinosaur. Thirty-four boxes of bones weighing 25 tons were hauled by horse and wagon 150 miles to a railroad depot and shipped back to the museum. Preparing, assembling and mounting the 72-foot-long, 12-foot-high beast took five men seven years.

Remington Kellog, a leading authority on whale evolution, directed the museum from 1948 to 1962, a period when it was modernizing its exhibits for the first time (replacing old mahogany-and-glass cabinets that had stood for more than 40 years) and instituting other major changes. It was in the 1960s that the Smithsonian established separate new museums to house its American history and art collections. New east and west wings were constructed for the Museum of Natural History in the same decade, vastly enlarging collection storage and laboratory space. At the same time, the museum was air-conditioned, an event old-timers considered the greatest single advance since 1910.

The collections kept growing and growing. Today the museum is the steward of the world’s largest assemblage of natural history items, with more than 126 million objects and specimens in its collections. The Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center in Suitland, Md., officially opened in May 1983, provides state-of-the-art conditions for storage and conservation of many of the Natural History Museum’s collections, as well as a library and advanced research facilities.

Today the Natural History Museum has an annual budget of approximately $67 million, and 450 full-time employees, including scientists; collaborating research associates and fellows; and a professional team of educators, exhibition developers, designers, information specialists, building managers, administrators, security personnel and support staff. Its scentific staff is organized in seven departments: anthropology, botany, entomology, mineral sciences, invertebrate zoology, paleobiology and vertebrate zoology. These programs address topics of current importance to society, such as biological diversity, global climate change, molecular systematics for enhancing the understanding of the relationship between living things, ecosystem modeling, and the documentation and preservation of human cultural heritages.

Last year, some 7 million curious visitors came to the museum to see the Sant Ocean Hall, the Hope Diamond, the Insect Zoo, the dinosaurs, plus other exhibitions in the museum’s dozens of exhibit halls. As visitors continue to flood the halls, behind-the-scenes—in laboratories from basement to attic and out in the field on several continents—museum scientists work to advance knowledge of the natural world and of man’s development.

This slide show features images from the National Museum of Natural History beginning in 1904. (Images courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives.)

Posted: 16 March 2010

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature