From the Secretary: The Running Fence: A personal encounter

In his book, Assembling California, John McPhee explains how, over the course of eons, the forces of plate tectonics created the land that would become the state of California. Tectonic forces continue to do their work in California, as the Pacific Plate steadily follows a north-by-northwest course, grinding against the more stable North American Plate. In northern California, the land ends abruptly along a coast formed by the plates’ boundaries where the cold Alaskan current surges against a rocky headland. During most of the year, powerful winds rise from the frigid ocean waters and surge inland to the warmer climes of the Great Valley.

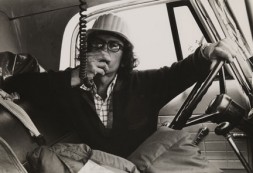

Christo on the intercom in cab of truck, mid-August, 1976. Christo and Jeanne-Claude Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California 1972-1976. ©Christo (Photo by WOlfgang Volz)

It is this dramatic and beautiful part of the world that artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude chose for their 1970’s “Running Fence Project.” This setting, like no other in the world, provided them with both grandeur and special challenges.

While attending graduate school at Berkeley and later, teaching at Stanford in the 1970s, I had come to love the northern California countryside and its picturesque wineries, dairy farms and cheese factories, framed by the hills that became wreathed in fog that rolled in from the ocean. I had heard of the proposed project, but, for my part, I could not imagine that anything like a “fence” could possibly improve or even complement the northern California landscape.

Christo "Running Fence (Project for Sonoma and Marin Counties, State of California)" Collage 1976 ©Christo (Photo by Wolfgang Volz)

I remember feeling both relief and deep respect when I actually saw the fence—in September 1976. Appearing almost out of nowhere, was a white, billowing 18-foot-high length of fabric running across the land—for more than 24 miles. Cloth panels hung from heavy cables, floating over the windblown hills and into the valleys between them—as far as the eye could see, eventually disappearing into the Pacific Ocean.

The white fence stood in contrast to the brown hills, and as the wind patterned and shaped the fabric, it flowed dramatically over the landscape in a sinuous pattern, forcing the mind to try to reconcile the unchanging hills’ three-dimensional curves with the ever-changing fence line. As the wind blew, the fabric panels moved and the fence seemed to be alive. Then, after only 14 days, the fence was removed, leaving only a memory. The purpose of their art, the artists have explained, is simply to create works of joy and beauty and to offer new ways of seeing familiar landscapes.

Hangers-unfurlers fight with the wind, Sept. 8-10, 1976. (Christo and Jeanne-Claude Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California 1972-1976.©Christo) (Photo by Wolfgang Volz)

Christo has explained why his vision requires such tremendous effort for an ephemeral work that exists only briefly: “I am an artist, and I have to have courage…Do you know that I don’t have any artworks that exist? They all go away when they’re finished. Only the preparatory drawings and collages are left, giving my works an almost legendary character. I think it takes much greater courage to create things to be gone than to create things that will remain.”

Fortunately for the Smithsonian, the American Art Museum’s current exhibition, “Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Remembering the Running Fence,” on view through Sept. 26, gives us all a chance to appreciate these artists’ remarkable accomplishment. The exhibition tells the fascinating story of the Running Fence project, including the 42 months of collaborative effort to obtain permits from 59 farmers and zoning variances from two counties and the coastal authority. Back then, I had no idea of the project’s complexity: 240,000 square yards of heavy woven white nylon fabric, 90 miles of steel cable, 2,050 steel poles, 350,000 hooks and 14,000 earth anchors.

Seeing the actual Running Fence during its brief existence in 1976 proved to be one of my most moving encounters with the power of art. The fence was large, dramatic and impossible to ignore. It was not on display in a museum but incorporated miles of one of America’s most beloved landscapes. The concept and scope of the project were audacious.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California 1972-1976, ©Christo (Photo by Jeanne-Claude, 1976)

I was doubly blessed to have the opportunity to meet Christo and Jeanne Claude in person, in 2008, when the American Art Museum first acquired the definitive record of “Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California, 1972-76.” Last month, I toured the exhibition with Christo and his project engineer—tragically, Jeanne Claude died last year. My two guides explained how they designed the nylon panels to withstand the powerful northern California winds and the engineering challenges of erecting steel posts and wire cables in that environment.

I love the exhibition, including the preliminary drawings that remind me of a much earlier day—before standardization—when building parts had to be individually designed, drawn and constructed. In the Running Fence drawings’ intricate details, you can see Christo’s mind at work, and begin to appreciate the enormity of his and Jeanne Claude’s vision, passion and achievement.

Posted: 1 May 2010

- Categories: