Taking the plunge

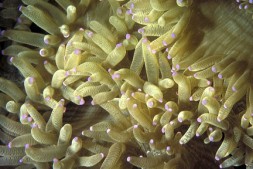

Organisms are best understood by observing them directly in their habitat. For marine organisms, however, their very habitat—water—often makes this challenging. Scuba diving has changed that. For example, coral was initially believed to be a plant. Eighteenth-century scientists used microscopes to determine that coral is an animal, but it was not until scuba was developed that researchers were able to study coral in its natural habitat for long periods of time. This lead to a much clearer understanding of coral and its communities and ecosystems.

Allowing people to stay under water for long periods of time has made scuba equipment an invaluable tool for the study of marine and freshwater environments. Since its development in 1943, scuba (originally an acronym for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus) has enabled researchers to dive longer and deeper and closely study millions of underwater species and their vibrant ecosystems.

To mark scuba’s important role in underwater science, the Smithsonian Institution is convening dozens of scientists on May 24 – 25 at the National Museum of Natural History for a special symposium: “Research and Discoveries: The Revolution of Science through Scuba.” Open to the public, those who wish to attend must register online at http://www.si.edu/sds/index.htm

“Without scuba our dive times would be restricted to the few minutes we could hold our breath, clearly not long or deep enough to make scientific observations or collect samples needed for our work,” says Michael Lang, director of the Smithsonian’s Marine Science Network and the Smithsonian’s Science Diving Program. “With thorough entry-level training, scientific scuba is a simple enough tool to enable its effective and safe use at many remote research sites.”

From left, Sherry Reed, Smithsonian dive safety officer; Michael Lang, director of SI Scientific Diving Program; Sam Benson, SI diving technician; Edgardo Ochoa, SI diving program specialist; Laurie Penland, assistant Scientific Diving Program specialist.

Scuba is not a finished product, however. As technological advancements are made, scuba will continue to grow and be an even greater resource to science and discovery. “As our knowledge of decompression sickness increases and engineering solutions for scuba regulators and dive computers evolve, the envelope of our working window in the underwater world will likely expand, opening up new depths and habitats for research and exploration,” Lang says.

Posted: 20 May 2010

- Categories: