On the Road in Alaska: The Secretary’s travel journal

(Click to read the first and second installments of the Secretary’s Alaska journal.)

May 24

Dynamic Grandeur–Kenai Peninsula

Surrounded by seas and studded with snow-covered mountains that plunge into the dark waters, the Kenai Peninsula is a place of awesome natural beauty. It seems to be an immutable force that is now as it has always been. Yet nature works as an invisible sculptor, shaping and re-shaping what might seem perfect to the human observer. In the course of time, the forces of nature create a dynamic landscape subject to sudden and spectacular change, but also one of inexorable processes that are only visible to the human eye when seen in the time shifts captured by photographs or measurements.

Surrounded by seas and studded with snow-covered mountains that plunge into the dark waters, the Kenai Peninsula is a place of awesome natural beauty. It seems to be an immutable force that is now as it has always been. Yet nature works as an invisible sculptor, shaping and re-shaping what might seem perfect to the human observer. In the course of time, the forces of nature create a dynamic landscape subject to sudden and spectacular change, but also one of inexorable processes that are only visible to the human eye when seen in the time shifts captured by photographs or measurements.

The Kenai Peninsula lies astride the subduction zone formed as the Pacific Plate plunges beneath the North American plate, conditions that birth large earthquakes. In the Kenai, this activity forms a “hinge line” where land north of the line subsides and that south of it rises. The land along the coast below the hinge line rose as much as 30 feet in the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake, while subsidence of up to seven feet occurred above the hinge line. Over thousands of years, some areas have risen and some subsided by hundreds of feet, changing coastal habitation patterns. Above the hinge point, leafless, gray “ghost forests” stand mute along the shoreline, evidence of the subsidence that lowered the trees into the saline waters of the sea along with ancient human settlements now submerged and lost to time.

The ample moisture provided by the oceans and the cold temperatures combine to create glaciers and ice sheets in the high country of Alaska, and these become sculpting forces of nature as they move slowly toward the sea following valleys and rivers. Steep mountain inclines at the coast have been shaped into magnificent fjords where glacial fronts cascade into the sea. The climate of this northern land also is subject to rapid change caused by perturbations of the earth’s heat engine. Multiple glacial retreats and advances have been documented over the past 15,000 years; the present phase is largely one of retreat—in some cases, dramatic retreat. In the Kenai, nothing stays the same for long except the grandeur of the scenery.

Marine life in the seas around the Kenai is among the most abundant in the world. The fast-running currents create 20- and 30-foot tides as they funnel into bays such as Cook Inlet. Runs of herring and salmon attract seals, sea lions and walrus while whales feed on krill colonies. Pods of orcas (killer whales) prowl the territory feeding on the wide spectrum of prey to be found, and, not to be left out, humans arrive in increasing numbers to enjoy the remarkable fishing.

Today’s itinerary calls for us to visit two areas of interest to the Smithsonian, both on the south side of the peninsula. The first lies within the boundaries of Kenai Fjords National Park where Aron Crowell and his colleagues have discovered a series of habitations by the Sugpiaq people, some dating back as far as 2,000 years and others much more recent, from as late as the 19th century. From here we will fly to the town of Seward to visit the Seward Sealife Center where we have collaborations, and take a boat out onto Resurrection Bay to see the rich marine life of this area.

Northwestern Fjord

From left, Bill Fitzhugh, Wayne Clough, Anne Clough and Aron Crowell prepare to depart for Northwestern Fjord.

Reaching Northwestern Fjord, our first destination on the coast, requires the services of a sea plane, which we acquire in Anchorage. Our pilot is Chuck, a veteran who fits the part—grizzled and a man of few words, but clearly in control of the situation. Our sea plane is a also a veteran, a 1957 De Haviland Beaver that seats five and a deep asymmetric idle that sounds a bit like a Harley Davidson. The Beaver lifts off the water in a businesslike manner, rising quickly over Anchorage and heading south for the mountains ahead that define the Kenai Peninsula. Although the mountains are only 4,000 to 5,000 feet high, the seas below feed moisture-laden winds that encounter frigid air and generate deep snowfalls in the highlands, forming the formidable Harding Ice Field. At 700 square miles, it is one of the largest ice fields in the United States. Below our wings are evanescent lakes that look like tourmaline jewels with waters clouded by the “rock flour” created by the grinding power of the glaciers.

Our flight takes us over the heart of the ice field at an elevation that allows for close observation of the sinuous flows of the glaciers feeding down the mountain valleys, carrying the marks of dark moraines at their edges, formed of crushed rock created as the glaciers grind against the rock surfaces. The frequent brown colorings on the surface contrasting with the white of the ice and snow are evidence of volcanic ash from recent eruptions in the area.

As we reach the far side of the ice field and begin to hone in on the Northwestern Fjord , the ground falls away toward the sea in steep slopes, carrying the glacier fronts with them, finally terminating in what appears to be a cascade of ice. The fjord looks the part, with its majestic snow-capped peaks surrounding a pristine bay. As the sea plane descends to land on the water, Chuck notes that we are truly fortunate to have a windless, partially sunny day as the region is much better known for wind and rain.

Chuck nestles the plane’s pontoons up against the beach so we can climb out into the shallow water and onto the beach. As soon as we turn around to take in the breathtaking scenery we find we are joined by a welcoming party of curious harbor seals, who poke their heads up out of the water to see who has come to their home on this day. Satisfied we are harmless, they go about their business with only a few of the clan watching from to time to time to insure that we keep our distance.

The presence of the seals in this enclosed bay is a reminder of why the Sugpiaq people would have settled in this location. It is rich with sea life that can be hunted from kayaks within the limited confines of the fjord.

Aron leads us around the spit of land that juts out from the rock wall of the fjord. He tells us that the spit is actually an end-moraine left by Northwestern Glacier, whose toe rested here only 100 years ago during the cold period known as the Little Ice Age, before beginning its seven-mile retreat during the warming temperatures of the 20th century. During the time that the glacier still rested here and when people occupied the site, harbor seals would have been especially abundant, raising their pups on the floating ice that calved from the glacier’s face. The moraine’s flat ground offers other sources of food, including plants that provide nutrients from their leaves and tuberous roots. Higher parts of the spit are forested with old-growth spruce and hemlock trees, which provided wood for building houses and gave protection from the Gulf of Alaska’s furious storms. Driftwood on the seashore was used as fuel for hearth fires and material for building kayaks and carving the implements of daily life. Even the ground in the wooded areas is a comfort, thickly covered with moss and grass that creates a soft, spongy surface that drains well and remains dry.

Early inhabitants would have found abundant food sources, both from the sea and the the plants and trees of the forests. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

Aron points out the outlines of several of the 30 dwellings at the ancient settlement, where excavations and radiocarbon dates demonstrate that Sugpiaq people lived from about A.D. 1225 to the early 1800s. Also evident are recent digging by bears who are waking up from hibernation about this time. Bill spots a beautiful, fleeting arctic fox sporting its white winter fur. It is clear this location provides is a rich habitat for both human and animal life.

This ancient site is one of hundreds Aron and his colleagues have found along the Kenai Peninsula and adjacent regions of the Gulf of Alaska. They dot the coast in places like this, where the action of water and ice has created protected bays that attracted diverse sea life and animals, and ultimately, the humans who sought them for food.

Here at this remote and pristine spot is also evidence of the ubiquitous presence of a recent invention of Homo sapiens: plastic. Plastic bottles, floats from fish nets and eclectic pieces of hat rims and other detritus are found all along the beach. Plastic is becoming a scourge of the modern world, accumulating at a disturbing rate and staying around— breaking into smaller pieces that find their way into the sea and onto our beaches, where they are injested by fish and other creatures and eventually, by us. The ancient people who honored their compact with the environment would be troubled that our kind does not concern itself with this plague.

We take a few more moments to savor the beauty of the fjord but are driven by the schedule to rejoin Chuck at the plane to lift off to our next destination, Seward and Resurrection Bay.

Seward and the Alaska Sealife Center

Our seaplane flies low across the rims of successive fjords towards the town of Seward. Chuck seems to know instinctively how close he can come to the jagged rocks of the fjord walls and this allows for a close-up look at their geology. We land on Resurrection Bay and venture into Seward on our way to the Sealife Center, a bustling facility that is located on the shore of Resurrection Bay. Seward is a picturesque small city that served Native groups and ultimately Russians as a safe harbor. Today it provides a harbor for the great cruise ships with their thousands of tourists that ply the Inner Passage. Seward is famous for having almost been wiped from the map by a 30-foot tidal wave that surged into Resurrection Bay after the 1964 earthquake. But the town survived and is continuing its comeback.

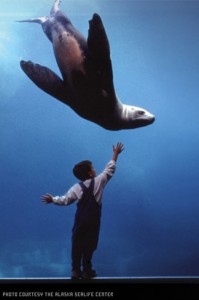

The Alaska Sealife Center provides education for visitors and locals alike about the Kenai Peninsula while conducting an ambitious research agenda that is focused on understanding the relationships between species and the ecosystem itself. Amy Haddow, the enthusiastic and outgoing head of development at the center, takes us on a tour. Representatives of marine birds and sea creatures are housed in the center so that visitors can see them up close. The most popular inhabitant is Woody, a 2,000 pound male Steller sea lion, who knows how to work the crowd when he chooses, but more often than not, prefers to snooze underwater.

“Wildlife cams” located around and beyond the Bay at bird and sea mammal rookeries allow scientists and visitors to remotely observe these animals in their natural habitat. The wildlife cams are effective tools for research as well as public education.

At lunch, the Sealife Center research staff, as well as collaborating faculty from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, review ongoing research projects. There are a number of issues of focus, such as the decline in populations of seals and sea lions. The decline may be partially a result of predation by orcas, stimulated by the 19th- and 20th-century commercial fishing of the right and humpback whales that were once were the orcas’ main prey. Warming water temperatures and encroachment by growing numbers of kayakers and cruise ships may also be part of the problem. Work is underway to educate recreational users of the park about these issues, and progress is being made.

Before we depart, Aron presents his work on the archaeology of Sugpiaq, Dena’ina and Tlingit settlements around the Gulf of Alaska, illustrating that humans have had a significant presence in this part of the world for a long time—more than 10,000 years. However, only recently has human impact on the environment been so significant and detrimental.

Our small party leaves the Sealife Center thankful for the opportunity to have visited and learned from center’s staff. They are dedicated and committed to helping preserve the natural beauty of the Kenai Peninsula and the ocean that laps its shores.

As our last activity of the day, the Sealife Center has arranged for us to take a tour of Resurrection Bay in one of their research boats with the stalwart Justin Jenniges as our captain. Justin makes sure that each of us leaves the center dressed in one of the all-encompassing orange Mustang survival suits that he says will keep us relatively dry as we cruise the bay in an open boat. His laconic delivery belies the fact that since we have been at the center, the wind has picked up, driving three- to four-foot waves down the bay. The flat-bottomed skiff that he is piloting was specially designed to capture and tag sea lions, with a bow that can drop down to welcome the unwilling creatures when they are lassoed and pulled aboard.

Fairly quickly after getting out of the harbor we realize why we have on the Mustang suits, as water sprays over the bow and the sides of our small vessel. It becomes an adventure, but after a while, even Justin concludes we are not going to get to the planned destination this afternoon. Instead, we steer over to the west side of the bay to gain some protection from the wind and the swells by running close to shore. Our spirits rise when we see the water ahead churning with sea lions who are feeding on herring and salmon.

As if on cue, these curious creatures gather near us in groups, at first, simply watching our approach and then frolicking in front of us. They seem to delight in individually diving underneath the boat and turning just before colliding with the group. After a particularly good run, the sea lions surface and bark excitedly, seeming to enjoy the opportunity to show off for us as much as we enjoy watching. There are many bustling groups of 10 or more noisy individuals.

With the day winding down we realize we have to return to the harbor. We are wet on the outside, but are buoyed by our experience, privileged to have seen up close some of nature’s most remarkable wonders and delightful creatures.

We bid Justin adieu at the airport where Chuck picks us up for the return flight home. The plane rises over the mountains of the Kenai Peninsula allowing a parting view of one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Posted: 28 June 2010

- Categories: