From the Secretary: Uniquely American stories, uniquely American storytellers

There is one painting in film director Steven Spielberg’s home that always attracted his children’s friends. “Nobody was stopped by the Monet, but [the Rockwell]…arrests everyone’s attention,” he explains. The painting, “Happy Birthday Miss Jones,” appeared on the March 17, 1956 cover of The Saturday Evening Post. The viewer looks over the shoulders of young students sitting properly at their desks—except one boy with an eraser on his head. Perhaps it was he who wrote “Happy Birthday Jonesy” on the blackboard before Miss Jones arrived, delighted to find her students’ surprise. (Because of copyright restrictions, we cannot reproduce the painting, but click here for a slideshow that includes “Happy Birthday Miss Jones.”)

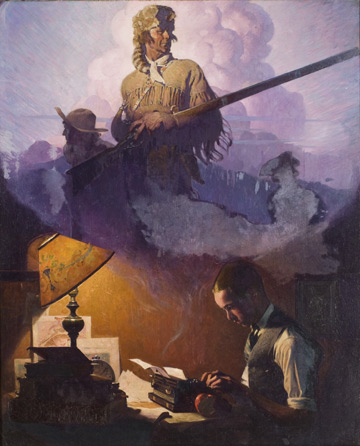

"And Daniel Boone Comes to Life on the Underwood Portable" Underwood typewriter advertisement, 1923, oil on canvas, 36 x 28 in. Collection of Steven Spielberg

Both Spielberg and his fellow filmmaker George Lucas admire Norman Rockwell and his innate ability to frame a story in a painting. Perhaps it is no surprise that Lucas owns a preliminary, large-scale pencil drawing of “Happy Birthday Miss Jones.” For the first time, the public can see the painting and drawing side-by-side, along with 55 other Norman Rockwell artworks in the exhibition “Telling Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg” at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum through January 2, 2011.

As filmmakers, both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg recognized a kindred spirit in Rockwell and each has acquired a significant collection of the artist’s work. “Telling Stories” is the first major exhibition to examine in depth the connections between Rockwell’s evocative images and the movies. Parallel themes in Rockwell’s paintings and Lucas’ and Spielberg’s films are explored, including love of family and country, small-town values, children growing up, the glamour of Hollywood, unlikely heroes and mythmaking.

The exhibition actually highlights four of our nation’s beloved storytellers: Rockwell, Lucas, Spielberg—and the Smithsonian, the nation’s storyteller. The exhibition and its catalog is based on significant original research by curator Virginia Mecklenburg, and breaks new ground in probing Rockwell’s fascination with Hollywood.

"Boy Reading Adventure Story" The Saturday Evening Post, Nov. 10, 1923, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 in. Collection of George Lucas. Lucas commented, "It's a painting celebrating literature, the magic that happens when you read a story, and the story comes alive for you." When working on Star Wars, he said, I realized that you could still sit and dream about exotic lands and strange creatures."

Rockwell once said, “If I hadn’t become a painter, I would have liked to have been a movie director.” He deliberately used cinematic devices such as staging his pictures, coaching his models, using costumes and props and hinting at prior actions. In “Miss Jones” we know the children came to school early to write on the blackboard because chalk spilled on the floor before Miss Jones arrives, her hat and coat still in hand. As George Lucas explains, “To convey a lot of information without spending a lot of time at it—Rockwell was a master at that.”

Most importantly, Rockwell creates an emotional connection between the viewer and the scene—in this case, we see what the children see: a smiling Miss Jones. It is this emotional connection, established by the artist with his audience, which Lucas says is common to both his and Spielberg’s movies.

We connect to art through personal experiences. For a boy growing up in rural South Georgia, there were no art museums. But the Saturday Evening Post was found in dentists’ and doctors’ offices and in homes like my own. That is how I experienced Rockwell’s art. The 323 illustrations that graced the cover of this popular magazine for more than 50 years influenced entire generations. Rockwell’s paintings evoked a life we lived in simpler times and the aspirations we held for our country.

Rockwell’s art captured our hopes and reflected our insecurity about whether we would measure up or be able to leave home for the wider world, a theme Lucas captured so unforgettably in his 1971 film, American Graffiti. Like Spielberg’s films, Rockwell’s art reflects times of pride and love of country, along with the changes that slowly came to our nation during the civil rights struggles as social justice was hard won.

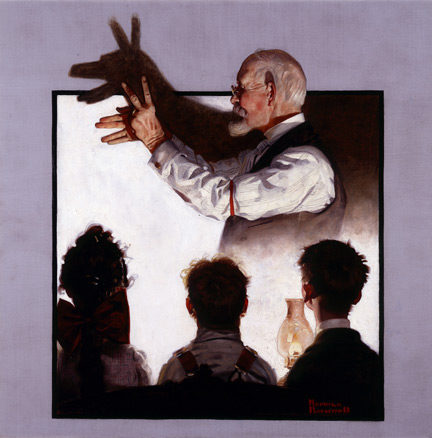

"Shadow Artist" The Country Gentleman, Feb. 7, 1920, oil on canvas, 25 x 25 in. Collection of George Lucas. The scene is presented from the point of view of the children who watch the shadow maker in awe. George Lucas noted, "Just by the tilt of the heads, just by their body language, you can tell they are completely fascinated by what they're watching, and you can see the pride…on the part of the shadow maker."

Years after I first saw Rockwell’s cover illustrations, I watched the rise of these two other American artists who transcended their times and even sometimes worked together to make fabulously successful movies such as the Indiana Jones series. Their films, like Rockwell’s paintings, helped define our country’s popular culture. Now, thanks to these two visual storytellers, hundreds of thousands of visitors can learn about Norman Rockwell by visiting the museum. Millions more will visit the website to experience the exhibition virtually. We are proud to host this storytelling bonanza!

Posted: 1 August 2010

- Categories: