With friends like these, who needs anemones?

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo has become the first in the zoo and aquarium community to successfully use coral larvae settling techniques to grow two species of anemones—an accomplishment that will provide the Zoo a unique opportunity to learn how anemones grow.

“We have many questions about how to care for these animals as they grow from larvae to adults,” explained Mike Henley, an animal keeper at the Zoo’s Invertebrate Exhibit who applied the technique to the anemones after they had spawned. “The oceans are not an infinite resource and so anything that we can learn about the captive management of coral and anemones will go far in our ability to conserve them.”

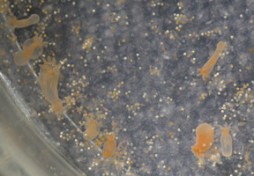

The anemones—both of which are commonly called Tealia red anemones under the species of Urticina—spawned in late April and early May, just days apart. Hours after they spawned, Henley collected the eggs and sperm from the more than 2,000-gallon tank and put them together in smaller tanks to increase the chances of fertilization. After fertilization, the larvae settled and metamorphosed into a polyp. Henley put some of the developing larvae in a circular tank—called a kreisel—that automatically stirs the water to prevent the larvae from binding to one another, which would kill the animals. The kreisel is the same tank Henley and others use in the field in Puerto Rico to hold coral larvae. Other free-swimming larvae went into a regular tank with aeration and rocks to settle on. Now the Zoo has hundreds of thriving anemones behind the scenes, all smaller than the tip of a pencil.

“Sometimes we take the lessons we learn with animals in captivity and apply that to conserving them in the wild,” said Alan Peters, curator of the Zoo’s Invertebrate Exhibit. “But here we were able to apply what we’ve learned both in the field and from ex situ work and it is yielding some exciting results.”

While anemones and coral are both in the Anthozoa class of animals, they differ in a few notable ways. Anemones metamorphose into a single polyp, while coral will divide into a second polyp and a third and so on, to form a colony. In addition, anemones have a muscular foot they use to attach to rock, while stony corals make their own calcium carbonate rock that they live on. But both can sting and are carnivorous, feeding on crabs, shrimp, fish and zooplankton. More than 1,000 sea anemone species inhabit the world’s oceans at various depths, from the sandy seashore up to the surface. Visitors to the Zoo can see six different species of anemones, including cold and warm water anemones. Although anemones are not endangered, ocean habitats around the world are in decline as the result of pollution, runoff and sedimentation, climate change, acidification and poor fishing practices.

Henley will continue to observe the anemones to learn about their growth rate and the conditions that are necessary to rear these species in captivity, including the food, light and water temperature they require.

“In the past if the anemones spawned in the tank, it’d be a big headache,” said Henley. “You’d have to do frequent water changes because when the gametes—or reproductive cells—get too concentrated and deteriorate, it causes the water quality to crash. That’s the common experience among many of our zoo and aquarium colleagues. But this was different—so far it’s amounted to young anemones that we will continue to learn from for months, even years, to come.”

Mike Henley is a little worn out after the third aneone spawning in less than a month. (Photo by Mehgan Murphy)

Posted: 1 September 2010