“I, too, have made a wee little book.”

(This article is an edited version of a post that originally appeared on the Smithsonian magazine blog, Around the Mall.)

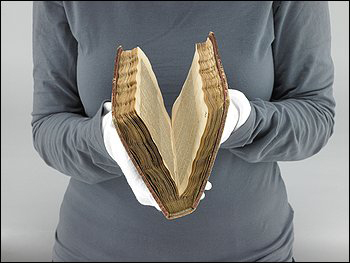

A 191-year-old national treasure, one that has resided at the Smithsonian Institution since 1895, is now in the care of conservators to undergo a specialized treatment for its long-term preservation. The stiff and torn pages of this document will be removed from their binding, stabilized, rebound and then the entire book will be stored in a custom-made protective enclosure. Additionally, each of the original pages will be carefully scanned to make high-resolution digital images of the document and a complete set of color photographs will be made, so that visitors and researchers will be able to access and read the precious document on-line later this year.

Conservator Janice Stagnitto Ellis demonstrates that the volume cannot be opened without damaging the pages. (Photo by Hugh Talman)

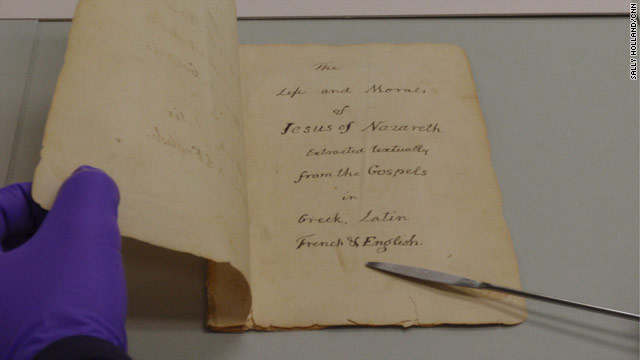

The artifact? It is an 86-leafscrapbook of sorts, measuring 8 and 1/4-inch by 4 and 15/16-inch. Bound in red morocco leather and ornamented with gilt tooling, it is entitled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. The little volume is best known as “Thomas Jefferson’s Bible. ” But it is not a Bible like any other.

Sometime during the winter and fall months of 1819 and 1820, the 77-year-old Jefferson created the book himself at his Monticello home. Using a knife, he cut passages out of six copies of the New Testament—two Greek and Latin, two French and two English—and rearranged his select passages into a chronological order. Jefferson’s Bible begins with Luke 2: 1-7, the account of Joseph and Mary’s journey to Bethlehem, and ends with Mathew 27: 60, the story of the stone rolled across the door of the sepulchre, after the body of Jesus is laid to rest. The passages all relate to the moral teachings of Jesus. There are two old world maps pasted behind the title page and Jefferson’s hand-written notes are scattered throughout.

But missing from the work are all mentions of miracles or life after death and the Old Testament.

“He’s trying to get to the essence of the teachings of Jesus Christ,” says curator Harry Rubenstein, chair of the American History Museum’s division of political history. “He removes those things that could not be proven by reason and thought.”

Rubenstein says that the document, one of the most significant of the museum’s Jefferson artifacts, reveals much about the third president. “Looking at it,” he says of the book as well as two of the original source books that Jefferson used to make his Bible, “you can almost see the thought processes of this elderly gentleman, Jefferson, going on as he assembled the book. . . .What is amazing to me, is he decides to save the source books, possibly to add something later, or if he has other thoughts.”

Jefferson had earlier made another version of his book and over many years corresponded with a number of close friends, including Benjamin Rush and John Adams, detailing his idea for creating the guide from “the very words only of Jesus.”

“I, too, have made a wee little book,” Jefferson wrote in 1816 of the earlier version, “from the same materials, which I call the Philosophy of Jesus; it is a paradigm of his doctrines, made by cutting the texts out of the book, and arranging them on the pages of a blank book, in a certain order of time or subject. A more beautiful or precious morsel of ethics I have never seen; it is a document in proof that I am a real Christian, this is to say, a disciple of the doctrines of Jesus.”

The Jefferson Bible, or the Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, was never meant to be published. Jefferson shared his thoughts on the topic with only a select group of friends and his family did not know of the book’s existence until after the nation’s third president had died. A Smithsonian librarian Cyrus Adler (1863-1940), who had learned of the Bible from one of Jefferson’s biographers, purchased it from his great-granddaughter Carolina Randolph for $400 in 1895.

In the museum’s paper conservation lab, the Jefferson Bible is now partially disassembled, a few of its pages are laid out on a table along with color photographs that document the book in its current condition. Two of the six source Bibles that Jefferson cut passages from are also on hand. Conservator Janice Stagnitto Ellis says that “time and age and oxygen and moisture have contributed to the pages of the book becoming less flexible, so that when it is opened, the pages crack and tear.” Conservators, she says, view the book as an assemblage of 12 different kinds of paper, six different types of printing ink, as well as the ink from the pen that Jefferson used to make notations in the margins. “The first thing we did was really look at it. That survey had 20,000 data points.” The analysis, she said, offered relatively good news. The Jefferson Bible was in a condition that Ellis described cautiously as “not bad.”

The treatment calls for the leaves to be removed from the binding, treated and resewn into the original binding in such a way that the pages can be turned without harm.

In 1902, Congress directed that 9,000 black and white lithographs of Thomas Jefferson’s bible be printed and distributed to new Congressional members as a gift when the lawmakers arrived in Washington, D.C. The act drew controversy when the Presbyterian Ministers’ Association of Philadelphia objected to the stripped down version of Jefferson’s Bible, saying that the book removed the deity of the doctrine of Jesus.

According to the museum’s press release, “Jefferson had no intention of publishing his work, rather intending it to be private reading material and not for a larger audience. He considered his and others’ religious beliefs a private matter that should not be subjected to public scrutiny or government regulation. He knew his beliefs could be viewed as unorthodox and would offend some religious authorities, and he knew that his views could be used against him by his political opponents.”

“The volume provides an exclusive insight to the religious and moral beliefs of the writer of the Declaration of Independence,” says Brent Glass, director of the museum, “as well as his position as an important thinker in the Age of Enlightenment.”

The newly conserved Jefferson Bible will once again go on view this November along with two of the source books Jefferson used, and an original copy of the 1904 printing in the museum’s Albert H. Small Documents Gallery. A lavish color reproduction offered by Smithsonian Books is due in bookstores later this fall. And the Smithsonian Channel is currently at work on an hour-long special on the Jefferson Bible.

(This post was written by Beth-Py Lieberman, an editor with Smithsonian magazine since 1986.)

Posted: 14 March 2011

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture