The Westinghouse letter: One young Civil War veteran at the crossroads

(Image: PRR D1 locomotive fitted with experimental Westinghouse air brake equipment during the 1869 trials on the Pennsylvania Railroad that led to the railroad’s adoption of the revolutionary air brake in 1870.)

Occasionally the routine of museum work is interrupted by the opening of a window to the past when one shares a long ago moment in someone’s life. One of those unexpected encounters occurred a few days ago as I worked in the electricity collections. I found myself aboard a warship in mid-1865, in the company of a young naval officer who would soon become one of America’s leading industrialists.

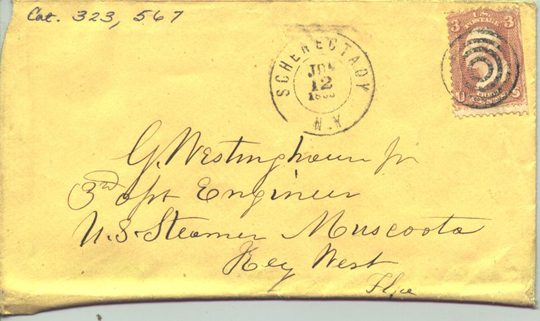

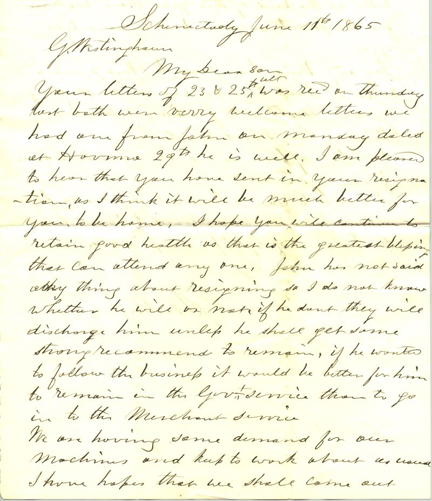

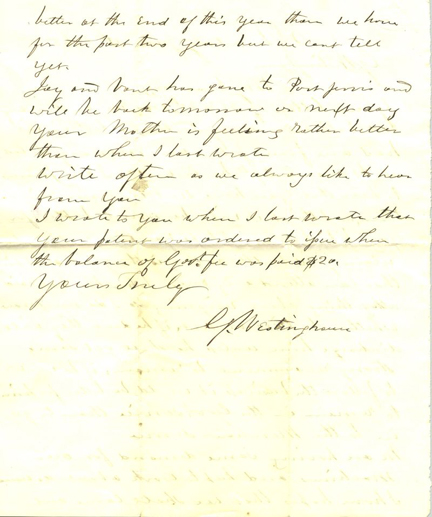

For several years we have been rehousing the objects in the electricity collections. We’ve replaced old storage racking with new cabinets, updated our database, and photographed objects. Most of the objects are three-dimensional but we do have some flat items. While working through a document box, I opened an old folder and came across an envelope addressed to George Westinghouse, Jr., postmarked 11 June 1865. That date caught my eye. One usually associates Westinghouse with the Gilded Age, not the Civil War. The letter had been donated by a grandson, Aubrey Westinghouse, in 1963.

As George Westinghouse, Sr., wrote this letter to his son, the Civil War was coming to an end. Robert E. Lee had surrendered his army to Ulysses S. Grant about two months before, although some fighting continued west of the Mississippi. The North still grieved for the assassinated Abraham Lincoln, gone only 8 weeks. The South wondered about the fate of Jefferson Davis, captured by Union forces one month before.

June of 1865 was a time of change and uncertainty for everyone in America, including a young George Westinghouse, Jr. Born in 1846, he enlisted in the Union Army in 1863, serving with a New York cavalry regiment. He transferred to the Navy in late 1864 following the death of his brother Albert, killed in battle. Another brother, John, already served in the Navy as an engineering officer. George too received a commission as an engineering officer and was assigned to a new steamship, U.S.S. Muscoota, that entered service in January 1865. In early May, the Muscoota was dispatched to Key West as the Navy sought to block Jefferson Davis’ escape from the country. By the time Westinghouse received this letter Davis was in custody and the ship awaited further orders.

As I read the letter, I felt the pace of activity in Westinghouse’s life. As the 18 year-old veteran waited for the Navy to accept his resignation, he thought about home and a return to civilian life. He had already filed for a patent on a rotary steam engine and doubtless was thrilled to learn of its impending issue. Having worked in his father’s machine shop before the war, he would have been pleased to hear that business prospects looked good. He would have been relieved to hear that John was well, and that his mother (I imagine still grieving over the death of Albert) was feeling better.

This letter gives a glimpse into George’s life at a crossroads moment. Both his teenage years and his military service were nearing an end and the future beckoned. He was considering college. Before the end of the year he enrolled in–and then dropped out of–Union College in Schenectady. With one patent pending, his thoughts surely turned to other inventions. Still single, he probably wondered about finding someone. He would not meet his wife, Marguerite Erskine Walker, for another two years.

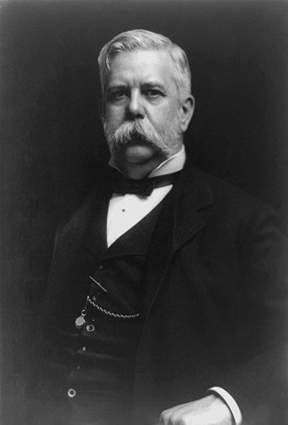

This letter prompted me to look closely at his personal history. When Westinghouse read this letter aboard the Muscoota, fame and fortune lay in his future. By the turn of the century he was wealthy and known nationwide as the inventor of a revolutionary railroad airbrake. As the promoter of an alternating current system for electrical power, Westinghouse and his company helped to electrify America. However as a young man in 1865 he was simply another Civil War veteran looking forward to going home.

This is an edited version of one post in a series commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War originally published by the National Museum of American History’s blog, O Say Can You See? Hal Wallace is the Associate Curator of Electricity Collections at American History.

Posted: 3 March 2011

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture