From the Secretary: The Smithsonian’s shining moment: The Haiti Cultural Recovery Project

“If you want to destroy a country, destroy its memory,” Czech Novelist Milan Kundera once said. That almost came true for Haiti after the devastating January 2010 earthquake, when Haiti’s art and historical documents lay in the rubble of collapsed museums and public buildings. Relying on Under Secretary for History, Art and Culture Richard Kurin’s contacts in Haiti and with other cultural organizations, the Smithsonian early on resolved to help, and assumed a leadership role in creating the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project.

Haiti's Presidential Palace, destroyed by the 2010 earthquake, remains in ruins. (Photo by Ken Solomon)

In June of 2010 I visited Haiti to view first-hand the efforts to establish the Project. (Here is my account of that trip.) One year later I returned with Richard and Johnnetta Cole, director of our National Museum of African Art, to see what had been accomplished and to thank the team. Other colleagues on this trip included Rachael Goslins, executive director of the President’s Committee on Arts and Humanities, and Eryl Wentworth, director of the American Institute for Conservation, both of whom have supported the Recovery Project. (Read the follow-up travel journal here.)

My visits to Haiti have convinced me of three things. First, the people of Haiti are remarkably resilient in the face of great challenges and possess a rich cultural tradition. Second, the recovery of the country at large from the 2010 earthquake is heartbreakingly slow, with over 1 million of the 9.7 million people in Haiti still living in tent cities. Third, the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project will leave a lasting legacy. It is succeeding because it is based on the right motivations and brings together a team of people who possess exceptional skills and a commitment that will not be deterred, even in the face of great odds.

The SI-PCAH delegation visits the devastated Centre d'Art site in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on June 21, 2011. From left, Stephanie Hornbeck (Chief Conservator, Haiti Cultural Recovery Project); Dr. Richard Kurin (Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture; Corine Wegener (President, U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield); Eryl Wentworth (ExecutiveDirector, American Institute for Conservation); Rachel Goslins (Executive Director, President's Committee on the Arts and Humanities); Axelle Liautaud (member Centre d'Art board), Dr. Wayne Clough (Secretary); Rosa Lowinger (Conservator, St. Trinity murals project); Olsen Jean Julien (Project Manager, Haiti Cultural Recovery Project); Dr. Johnnetta Cole (Director, National Museum of African Art). (Photo by Erickson Pierre-Louis)

Cultural Recovery Progress

The Project to help recover cultural artifacts in Haiti has produced remarkable results. So far, more than 26,000 works of art, paintings, sculptures, 3-D objects, books and historical documents have been rescued and stabilized. Dozens of conservators from the Smithsonian joined with others who volunteered from museums around the United States to aid in the effort. Just as important, 85 Haitian artists and museum specialists have also been engaged in the project and trained to carry out the recovery work. They have learned how to inventory, stabilize, surface-clean and safely store artworks and will continue to do so when our initiative concludes in November.

The progress of the Project comes from an outstanding partnership. Early on, the Smithsonian worked with the State Department, the President’s Committee for Arts and Humanities, the Broadway League, the Blue Shield, the American Institute for Conservation, UNESCO/ICCROM, and Haiti’s Presidential Commission for Reconstruction, its Ministries of Culture and Tourism, and La Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (The Knowledge and Freedom Foundation). All participated with a single goal: to rescue Haiti’s cultural patrimony.

As Rachel Goslins, executive director of the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities, said, “So often the reality of these kind of projects, which are complicated, tricky and conceived of in moments of great need, fall short of the visions and good intentions that created them. But, the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project is one that has, if anything, even exceeded our expectations. I was particularly moved by the words of the head of The National Library of Haiti, who said, ‘After the disaster, there were many who promised to help. But, you are the only ones who actually came, and did what you said you would do.’”

Then and Now

During my first trip to Haiti nearly a year ago, we were just beginning our recovery efforts, focusing on relationship-building and establishing a base for operations. Outreach efforts to museums and artist cooperatives produced many artworks that needed to be stabilized and treated, so we outfitted our studios with equipment and materials. In time the project took off and gained the trust of Haitian cultural leaders.

On my recent trip to Port-au-Prince in June, I found a country still struggling with its recovery. While most of the rubble is now off the streets and some rebuilding is occurring, much remains to be done, and most public buildings are still in ruins, including Haiti’s Presidential Palace.

Part of a mural carefully removed from the crumbling walls of the Episcopal Cathedral. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

The first stop on my trip was to the site of the Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, which collapsed during the earthquake. Fourteen larger-than-life-size murals depicting New Testament scenes once adorned its walls, and only three—painted by Haitian masters Préfète Duffaut, Castera Bazile and Philomène Obin—remained after the earthquake. I had seen the site on my first visit, and we discussed then if it would even be possible to save the remaining murals. Specialists Viviana Dominguez and Rosa Lowinger were brought in to work with a team of four Haitian artists to tackle the complex task of removing the murals. The murals had been successfully removed and are now being stabilized at the Cultural Recovery Center. Given that the Cathedral walls could have collapsed in the intervening time, and the magnitude of the technical difficulty of removing the delicate murals, this outcome is a small miracle.

A drawing by a Haitian child featured in the exhibition "The Healing Power of Art."(Image courtesy of the Government of Haiti)

Saving Treasures and Memories

From June 2010 to February 27, 2011, the National Museum of African Art presented the exhibition, The Healing Power of Art: Artworks By Haitian Children After the Earthquake. Upon seeing this exhibition, over 5,000 children from more than 40 states and more than 30 countries, including China, South Africa and Pakistan, drew pictures and wrote well wishes for the Haitian children. On this trip to Haiti, Johnnetta delivered a stack of drawings and notes that we recently received from a group of elementary school children in New York who had seen the exhibition. As Johnnetta said, “The Smithsonian and other colleagues are performing one miracle after another as they rescue, recover and restore Haitian artwork, artifacts, documents and architectural treasures.”

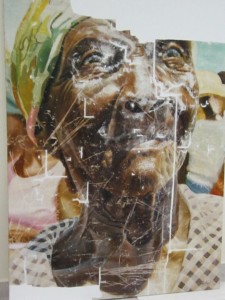

This detail from a painting by Mario Benjamin shows the damage it suffered in the earthquake. (Photo by Jean-Menard Derenoncourt)

The major effort of the recovery work has focused on saving artwork through stabilizing, surface-cleaning and storing. In special cases, artwork of particular cultural significance has been restored. When I visited our painting studio with Stephanie Hornbeck, the chief conservator who joined the project after she retired from the African Art Museum in January 2010, we observed two prominent Haitian artists restoring a painting by Mario Benjamin, which had once hung in the Presidential Palace. After the earthquake, this painting was crumpled, torn into two large pieces, and suffered 58 additional tears. Using an ultraviolet light to detect damage and illuminate areas where restoration has taken place, Stephanie showed me the meticulous work that had been done on this important work of art. To date, about 95 works of art have received more involved treatment, requiring aesthetic re-integration.

Teamwork

Stephanie Hornbeck has been the leader of the Smithsonian’s conservation effort in Haiti. Olsen Jean Julien, a former Minister of Culture in Haiti and a program coordinator for the Folklife Festival in 2004, has been the project manager and “go-to guy” from the beginning. He served as an important player in the partnership with the Haitian Government.

Jean-Menard Derenoncourt and Franck Louissaint treat the Palais National's Mario Benjamin painting. (Photo by Stephanie Hornbeck)

The leadership of Richard Kurin was essential in forming and maintaining our partnerships and keeping the logistics working. It was through his good offices that the Les Petits Chanteurs, the children’s choir of the Episcopal Cathedral, were able to perform at the American History Museum in Flag Hall last September. On my first visit to Haiti, Richard and I had been moved when we heard them sing as they practiced in a covered space behind the collapsed Cathedral. Reflecting on their performance at our American History Museum, Richard said, “The Haiti Cultural Recovery Project has always been about the voices of the Haitian people. Its aim has been to save those voices of the past, which speak to us through art, artifacts, books and archives, so they may provide inspiration to Haiti’s children who will speak and sing and create Haiti’s future.”

Corine Wegener, president of the U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield, brought her extensive experience in cultural recovery work to help organize the overall project. We owe her a great debt. The American Institute for Conservation also helped supply nearly three dozen volunteer conservators who joined many employees from the Smithsonian who took time from their normal work to travel to Haiti and help in the recovery project.

Detail of the Mario Benjamin painting during inpainting and restoration. (Photo by Jean-Menard Derenoncourt)

I am proud to be associated with the remarkable people who gave their time and talents to make this project a success. At the June meeting of our Board of Regents I gave a briefing about the recovery effort. Sen. Patrick Leahy, one of our Regents, who has a long-standing interest in Haiti and its culture, commented that this represented a “shining moment” for the Smithsonian. I agree.

A Future Model for Cultural Diplomacy

We are continuing to work with other agencies, including the State Department and key institutions in the private sector, to improve communication and coordination to help make a difference in situations of international crises. I am proud of, and inspired by, our work in Haiti because I believe it is a successful model. Cultural recovery efforts demonstrate our respect and support for the people of another country ravaged by earthquake, flood, civil unrest or conflict. Our work in Haiti is just the beginning as we work to become an even greater resource to our nation—and to the world.

Posted: 12 July 2011

- Categories: