How hot was it during the Battle of Bull Run?

This post by Assistant Archivist Ellen Alers was originally published by the Smithsonian Institution Archives blog The Bigger Picture.

“What were weather conditions during the First Battle of Manassas/Bull Run? I Googled it and looked on your website, but wasn’t able to find this information. I just need the temperature, humidity and wind speed. Thanks.”

This is a typical example of requests that comes in to the Smithsonian Institution Archives about weather data for a specific event. And it’s not as simple a question to answer as you might think. Eyewitness accounts say the day of the battle was, “hot and sultry.” That hasn’t changed much for Julys in Northern Virginian since. But do more specific numbers exist?

Joseph Henry, First Secretary of the Smithsonian, April 1873, by Thomas W. Smillie, Carte de visite, Smithsonian Institution Archives, SIA2009-1254.

Today, 24/7 weather coverage and Doppler radar reports are available because sophisticated instruments gather and transmit data continuously. This, however, was not the case in the 1861, although things had gotten pretty darn close. Starting in 1847, Joseph Henry, first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, developed a network of hundreds of enthusiastic volunteer observers (crowdsourcing 19th century weather geeks) to take measurements for the Smithsonian Meteorological Project. They collected readings for temperature, barometric pressure, wind speed, humidity, cloud conditions, and precipitation. They also reported on “casual phenomena” – tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, auroras, and meteor strikes.

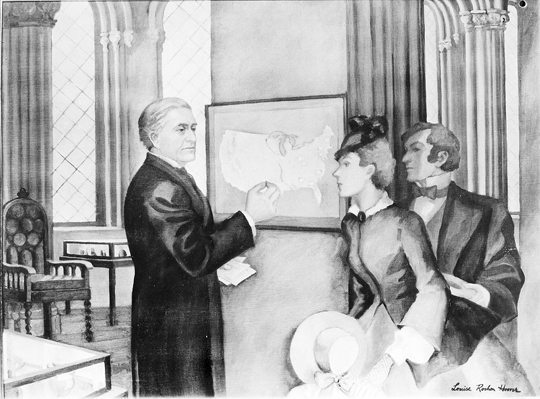

By 1859, a far-flung network of 600 observers, from Canada to the Caribbean, telegraphed data daily to the Smithsonian. The volume and speed of the reports enabled Henry to devise a color-coded map displaying current weather conditions throughout the nation. As conditions changed, so did the map, which became a popular attraction in the Smithsonian Castle. But you didn’t have to travel to the Castle to see which way the wind blew. Henry shared his data with the Washington Evening Star newspaper and, in May of 1857, it began publishing daily weather reports from as many as twenty US cities.

So there was lots of data; but do we have what the Civil War researcher needs? The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 damaged the meteorological project. The linchpin of its success, the telegraph, was flooded with dispatches from the front and other wartime business as observers took up arms on both sides. Needless to say, the flow of data was seriously curtailed. It appears unlikely that the weather was reported for the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. And if it was, where is that information now?

After considerable lobbying following the war, the national importance of Henry’s weather project was recognized by the US government. In 1873, the data from Smithsonian Meterological Project and responsibility for its network of observers was turned over the US Signal Corps. Records from the Smithsonian Meteorological Project, 1848-91 are now in the custody of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and can be found in two locations, subsectionRG 27.3 with related records are in subsection RG 27.5.7.

This image is of a painting by Louise Rochon Hoover, titled, "Professor Henry Posts Daily Weather Map in Smithsonian Institution Building, 1858." Joseph Henry, the first Smithsonian Secretary, is depicted showing visitors the weather map displayed in the Smithsonian Institution Building and updated every day. 1933. Smithsonian Instititution Archives, Image ID# 84-2074.

Now, whether there was an observer at Manassas Junction or in the vicinity who transmitted data during the first battle, I do not know. But I know where to look, so that’s where I pointed the researcher. I’ve never heard back as to whether anything has been found. But if the numbers weren’t there, diaries, reports, newspaper stories and eyewitness accounts would be every bit as valid when trying to understand the environmental conditions on the battlefield.

For more information on the Smithsonian Meteorological Project see, “Joseph Henry: Father of Weather Service” by Frank Rivers Millikan and “Joseph Henry’s Grand Meteorological Crusade” also by Frank Millikan,Weatherwise, October/November 1997 (PDF available on request osiaref@si.edu).

Posted: 21 July 2011

-

Categories:

Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture

Dear Mr. Talman:

Thanks for the link to the Science Service release. I’m always so pleased when others share what they’ve found.

Just an aside.

http://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/whytheweather/1932/19320125.pdf