On the road in Haiti: The Secretary’s travel journal

The Return Visit: June 21- 22, 2011

It has been over a year since we established the Cultural Recovery Center in Port au Prince, Haiti, to help recover and restore that nation’s rich artistic and cultural heritage after the devastating earthquakes of early 2010. Richard Kurin, our Undersecretary of History, Art, and Culture, was our team leader–using all of his skills from a career of field research in anthropology to pull together an international team of organizations and dedicated, determined individuals willing meet the demands of this challenging effort. In June 2010 I made my first visit to Haiti to see how our initial efforts were taking hold. What I saw encouraged me but I was overwhelmed by the scope of the work required and the massive level of destruction in this small country.

One year later, this visit gives me a chance to see first-hand the progress made by our cultural recovery effort as well as overall restoration efforts for the country. The trip was organized by Richard and his staff. My fellow travelers include:

- Rachel Goslins – Executive Director, President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities;

- Johnnetta Cole – Director, National Museum of African Art;

- Cori Wegener – President, U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield;

- Eryl Wentworth – Executive Director, American Institution for Conservation;

- Stephanie Hornbeck – Chief Conservator, Haiti Cultural Recovery Project; and

- Rosa Lowinger – Conservator, Haiti Cultural Recovery Project and specialist for recovery of the murals in the Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral.

Port- au-Prince

Port-au-Prince and its Toussaint L’ouverture International Airport welcome us with hot and humid weather and the cheerful rhythms of a Haitian Kompa band. We are greeted by Olsen Jean Julien, Managing Director of the Haiti Cultural Recovery Center. Olsen is the indispensable man, a cultural expert, an engaging personality, knowledgeable about the workings of the Haitian government, and a guy who gets things done, even if it means reasoning with a gendarme at a barricade who has a gun. He sees to it that we are whisked through customs and are on our way in short order.

Lunch is the first order of business at the delightful and slightly funky Hotel Oloffson. Sitting on a hill off a shaded street, the hotel has seen better days, but it has grown old with charm and dignity and is surrounded by a gracious canopy of shade trees. We take lunch on the wraparound porch and renew acquaintances while enjoying sandwiches.

While a number of us were here a year ago, this is Johnnetta’s first visit to Haiti in more than 20 years. Although unable to join us on last year’s trip, she was directly involved with the Smithsonian effort to help Haiti and raise awareness of the country’s plight. The African Art Museum mounted a special exhibition of Haitian children’s art created with the impressions of the earthquake fresh in their minds. She is bringing with her letters written by American children who were moved by viewing the Haitian children’s art. The letters will be given to Philippe Dodard, an artist who, with then-First Lady of Haiti Elizabeth Preval, organized a makeshift school for Haitian children. Philippe will then share the letters with the students.

Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral

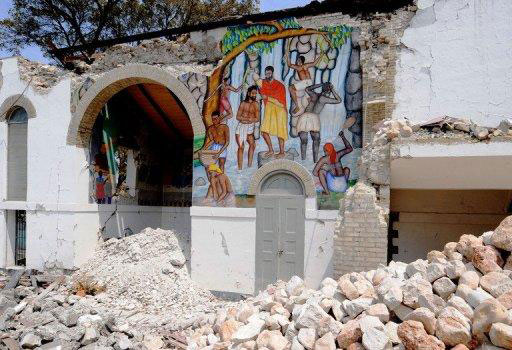

Our tour for the day begins with a trip to the Holy Trinity Episcopal Cathedral that I look forward to with high anticipation. When I last saw the Cathedral, it was in ruins, its roof collapsed inwards and the walls standing forlornly in various stages of disrepair. Lost or lying on the ground in myriad pieces were portions of the 14 great murals painted on the walls by Haitian masters, including Prefete Duffaut, Castera Brazile and Philomene Obin. By luck, three of the murals, or portions of them, remained in place on the wall remnants. This posed one of the challenges to the cultural recovery effort: Could the murals be removed and saved, or were they yet another sad loss to Haitian culture?

Interior view of the Episcopal Cathedral Sainte-Trinite in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, destroyed in the January 12, 2010 earthquake. (Photo courtesy France 24)

As we stood in the remains of the Cathedral on my first visit and pondered the fate of the murals, we were surprised as the sounds of music filled the air. Behind the collapsed nave walls and under what remained of covered space was a children’s orchestra and nearby, a children’s choir.

The very idea of these youthful victims of the earthquake making music reinforced a sense of humanity for those of us who wondered if hope was lost in this distraught land. Richard Kurin later made arrangements for the choir to perform at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of National History during a U.S. tour. Their performance captured the imagination of all who heard them.

Saving the remaining murals has been an exciting and challenging special Recovery Center project over the past year. There were perhaps more reasons to expect disappointment than success. The walls might collapse before any recovery efforts could be mounted. And even if the masonry walls remained precariously in place, could the murals be removed from them? The Recovery Project engaged a team to tackle this challenge consisting of specialists Viviana Dominguez, Rosa Lowinger and four Haitian artists.

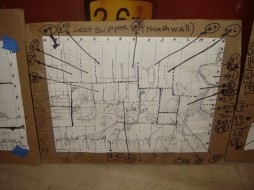

As we stood before the Cathedral walls on this trip, Rosa described the riveting story of the removal of the murals. The team had detached the murals inch by inch, using cracks created by the earthquake itself and selected cuts made with saws. Each piece was carefully mapped so it could be precisely replaced. The pieces were carefully packed and taken the Cultural Recovery Center for preservation and documentation.

The blank walls of the Cathedral after the surviving murals have been removed are are precariously supported and could collapse at any time. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

Before we leave we hear a presentation from representatives of the Cathedral about plans for its restoration. The Cathedral itself will not be restored, but instead its remnants will become a memorial and be surrounded by a complex including a new cathedral, museum, classrooms for youth education and buildings for community services. It is a bold plan with sound reasoning, but a challenge for fundraising. The remaining murals will be returned and remounted so visitors can view them within the memorial site.

Centre d’Art

We depart the Cathedral for the Centre d’Art. Travel along the crowded, narrow roads of Port-au-Prince is always exciting, but I can see that progress has been made since last year. Although many buildings still lie in ruins and over a million people still live in tent cities, much of the building rubble that blocked the streets is gone. Although not prevalent, there are clear signs of rebuilding and repair of damaged walls and buildings.

Before the earthquake, the Centre d’Art was a vibrant artists’ cooperative where artists were provided with supplies and studio space. The earthquake destroyed the building, but spared thousands of works of art that at the time of our first visit were at risk due to inadequate storage conditions. There is much to be thankful for on our return visit. After carefully crafting agreements for how the art works would be handled, they were transferred to our Recovery Center where each has been cleaned, digitized and documented in a manifest. They are now secure and ready to be transferred back to the Centre when it is able to receive them.

The crumbling remains of the original building at the Centre reminds us that progress in rebuilding Haiti is painfully slow. Surviving wall remnants tower above a chaotic pile of brick, wood and rubble, waiting patiently for gravity and time to bring them tumbling down. We are joined at the site by Aixelle Liataud, who is the director of the Centre. She is a gracious presence throughout our visit and expresses gratitude for the work of the Recovery Project since it allows the Centre access to its collection as the Centre works to rebuild itself.

From left, Stephanie Hornbeck, Richard Kurin, Cory Wegener, Eryl Wentworth, Rachel Goslins, Aixelle Liataud, Wayne Clough, Rosa Lowinger, Olsen Jean Julian, Johnnetta Cole.

Cultural Recovery Center

The final stop of this day is the Cultural Recovery Center itself. Located behind the walls of a compound owned by a Haitian businessman, its working space occupies one three-story building and several temporary structures. Storage for art is provided by a number of metal containers and in spaces inside the building. Stephanie Hornbeck has presided over the recovery work and Olsen has dealt with the myriad administrative issues required to keep the work on track. We were fortunate to draft Stephanie into service because she had retired as conservator for the Museum of African Art before the earthquake occurred. Her dedication, skill and hard work is one of the main reasons for the success of the project.

Stephanie and Olsen take us on a tour that focuses on different aspects of cultural recovery. In various rooms, Haitians are working in teams on projects of the moment involving paintings, sculpture and historical documents. They are using equipment that was brought here piece by piece by each member of the team who originally came to Haiti. Over time, the equipment pool has reached an adequate level; the spirit and commitment of the team more than compensates for any lack of sophistication in resources.

A visitor to the compound is struck by the incongruity of the work of the Haitian businessman and that of the Recovery Center. The genial businessman leases porta-johns and sells tires to the construction companies active in Port-au-Prince, enterprises that take up the front of the compound. In the rear, fine art and great murals are being restored by our dedicated team. Somehow, it all works!

Some of the works of art being treated are considered masterpieces and will be returned to prominent sites such as the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH) or the Presidential Palace, while others are notable works that are part of the national patrimony. Most of the efforts of the Center are about stabilizing art, not restoring it. Although a surprising number of artworks were not damaged during the earthquake, some of the masterpieces were. These special works are being restored using accepted processes established by the conservation profession. Stephanie takes us to a room where two Haitian artists are restoring a painting by Mario Benjamin that hung in the Presidential Palace and survived the earthquake, although seriously damaged. The restoration process is painstaking and is documented within the painting itself so that future scholars can see what was done during restoration vs. the original work.

Storing the thousands of paintings and sculptures that are being stabilized is a challenge, but also an opportunity. Each work is digitized and added to a manifest so that its place is established and memorialized to identify its location in storage. For the first time, the collections are documented and accessible to those seeking to use them. In portable facilities outside the Recovery Center building, the team working on the Episcopal Cathedral murals are carefully taking off adhesive coverings used to give the murals stability during removal and transport. Each piece of a mural is assiduously assigned a place in a map that establishes how the pieces will be placed to recreate the masterpiece in the future.

My strongest impression of the visit to the Recovery Center is of the Haitian artists and recovery team. They clearly are moved by the work they are doing and understand what it will mean to the country in the future. Many of them are accomplished artists in their own right and several jointly created a mural on a plywood wall outside the Center. It is made from the rubble of buildings collapsed in the earthquake and uplifts with its vibrancy and whimsy. To me this mural reflects the spirit of Haiti, bruised but still creative and resilient.

Our convoy of vehicles whisks us through the busy streets of Port-au- Prince from the Cultural Recover Center to the Karibe Hotel, our accommodation for the evening. It also provides the location for our evening celebration where all of those involved in the Cultural Recovery Project will gather for dinner and a press conference. This event is hosted by Olsen; Patrick Delatour, the Minister of Tourism and head of the National Reconstruction Commission; Daniel Elie, director general of ISPAN standing in for the Minister of Culture and Communication; and Francoise Thybulle, director general of the National Library of Haiti. It is an occasion to celebrate the success of the project. Our Haitian friends are gracious in their remarks and make it clear the results of our efforts are significant and lasting. Speaking from our perspective, I express our gratitude for the friendship and partnership we have found with our Haitian friends in this unique initiative.

Lehmann Collection

The next morning we are greeted by a day of delightful Haitian sunshine and cool morning air. Following a breakfast with my fellow travelers, our agenda calls for a series of short visits including the Lehmann Collection, the Nader Gallery and the MUPANAH. The Lehmann Collection provides a fascinating look into the work of folk and religious artists who created art reflecting the traditions of Haiti.

Artistic representation of religion in Haiti includes influences from European religions, African spiritualism and voodoo. In several rooms dozens of voodoo-based figures made of leather with mirrors for eyes lie in wait for visitors. In voodoo ceremonies they were used to peer into the souls of penitents. Looking at these figures gives me a sense of foreboding and I am glad to move on to another part of the collection! Presiding over this menagerie is Madam Lehmann, a wonderfully wise and elegant 80-year-old. Over time, the collection crowded her out of her house, and she moved across the street so the collection could continue to grow. There is hope to build a museum for the collection and we discuss the possibilities, the most promising of which seems to be a site which was unfortunately transected by the fault from the recent earthquake. I put on my earthquake engineering hat and we discuss what might be done to make the site suitable for a museum. There are not that many good answers, although it could be done if money is no object. Unfortunately, it almost always is.

Stephanie and her colleagues have assisted Madam Lehmann in cleaning and documenting some of her vast collection. Much remains to be done but progress is being made in preserving this important part of Haitian history and culture that is still vibrant today.

Mold damage can be seen on these paintings saved from the collapse of the Nader Museum in 2010. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

Nader Gallery

Next up is the Nader Gallery where we are greeted by Georges Nader. I last saw Georges on my first visit to Haiti. We met at the site of his family’s Haitian art museum which was flattened by the earthquake; sheer good fortune allowed his sleeping parents to escape injury. The Recovery Project has provided Georges with advice on stabilization and restoration of his collection of Haitian art, which is one the very best in the world. The new gallery is welcoming with open spaces flooded with natural light. he walls and spaces are filled with works that are vibrant with the bright colors typical of Haitian art. Georges take us on a tour of the Gallery and on the third floor shows us the space he created for art recovery.

Thousands of paintings from the Nader Museum have been restored and are providing a source of income for the artists who depend on his sales. As we are about to leave, Johnnetta Cole purchases a painting of the earthquake-damaged National Cathedral. It shows the Cathedral with its roof collapsed but with magnificent stained-glass windows intact in the remaining walls. The painting is a poignant reminder that those very windows were stolen and sold on eBay before our Recovery Project could save them.

Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien

Our final stop is at MUPAHAH, the national art museum, which largely survived the earthquake, in contrast to its neighbor, the Presidential Palace. MUPAHAH is mostly housed underground. Being underground helps buildings manage the motions of an earthquake by moving with them, not in opposition to them as occurs for above-ground structures. The Recovery Project has assisted tMUPAHAH in restoring its air conditioning and humidity control systems, much needed to protect the art and historical documents housed within. It is encouraging to see crowds of people in the museum and dozens of school children participating in field trips. Surrounded by tent cities and the collapsed Presidential Palace, the museum stands as a beacon for Haiti, and a symbol of hope.

Our convoy takes us from the MUPAHAH to the airport for our trip back to the United States, only a short plane ride a way but a world apart from Haiti. Haiti has a new president and its people new hopes for the future. We can only wish them well and urge our country to continue to find ways to help Haiti. As early as November, the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project will come to an end, at least as far as our efforts are concerned. I am optimistic that the Haitians who have learned about recovery and restoration will continue the work of the Project. There is still much to do.

Posted: 8 July 2011

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Feature Stories , From the Secretary , History and Culture

I applaud this wonderful effort being put forth by the Smithsonian Institution. I look forward to the future plans for Haiti and the rich history it has.