From the Secretary: The Jefferson Bible: Sharing a National Treasure

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is performing a specialized conservation treatment to ensure the long-term preservation of Thomas Jefferson’s Bible, a small handmade book that provides an intimate view of Jefferson’s private religious and moral philosophy acquired by the Smithsonian in 1895. (Photo by Hugh Talman)

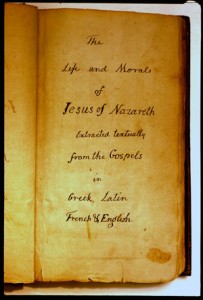

Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” As a leader in the call for universal elementary education, he devoted himself to creating new forms of learning in support of a new form of government. Although he could not get this passed into law in Virginia, his efforts laid the foundation for its ultimate acceptance. He was the founder of the University of Virginia, a non-secular, publicly supported institution that emphasized general education, including science, taught by scientists—unusual in its day. Once he left public office, he again focused on an intensely personal project and created what he entitled the “Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth Extracted Textually from the Gospels in Greek, Latin, French and English,” a document that came to be known as the Jefferson Bible. Jefferson sought to put into one document what he believed to be the seminal moral lessons from the New Testament gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It was completed in 1820 when Jefferson was 77 and just one year after the opening of the University of Virginia.

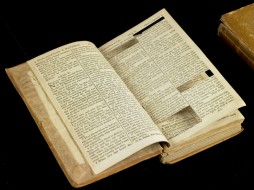

This source Bible shows how precisely Jefferson cut passages to paste in his compendium. (Photo by Hugh Talman)

Jefferson created the text for his bible by precisely cutting passages from six editions of the New Testament and pasting them onto pages that were ultimately bound to form a book. This was not the first time he had attempted to create such a document. During the last term of his presidency, he created an earlier version, but he felt it was inferior, so he created a second. He knew the idea of cutting out parts from the Bible would be controversial to many, so he never published it and chose only to share the news of its existence with a few close friends. Correspondence between Jefferson and his friends suggests that he regularly read from his volume before going to bed.

Conservation and Exhibition

Thanks to the research and efforts of Dr. Cyrus Alder, Librarian of the Smithsonian Institution from 1892 to 1905, the Smithsonian purchased the Jefferson Bible from Jefferson’s great granddaughter in 1895. This November, the National Museum of American History will open an exhibition on this extraordinary document and its history, curated by Harry Rubenstein and Barbara Clark Smith. It is based on two years of painstaking work by staff at the American History Museum, with the help of SI Libraries, SI Archives, the Museum Conservation Institute, Smithsonian Books, Smithsonian Channel, and Smithsonian Media.

Recreation of Jefferson creating his bible from the Smithsonian Channel documentary. (Photo by Rob Lyall)

For more than 40 years, I have owned, and often referred to, a copy of the Jefferson Bible. When I received an invitation to visit the conservation lab at NMAH for a personal look at the conservation work on the original document, I jumped at the opportunity. Janice Stagnitto Ellis, paper conservator at NMAH, showed me loose folios with pasted cutouts from the Bible that that had stiffened over time and were peeling at the edges. Remarkably, Jefferson had from time to time actually edited the Bible, removing a single word for grammatical clarity—for example, cutting out “as” in “For as in the days of the flood” (Matt. 24.38). Because Jefferson did the cutting work himself, it was revealing to see the precision of each excerpt he had extracted. I realized this was as close as I could ever be to the man himself, and I felt lucky to be there that day.

Conserving the Jefferson Bible

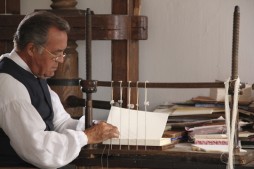

Janice, Harry and their team have established the history behind the book itself. Once the work was completed in 1820, Jefferson sent his pages to Frederick August Mayo, a Richmond bookbinder. He had complained to Mayo that American bookbindings were too “spongy”, so Mayo stitched Jefferson’s pages together in a special form of French-style binding, which has a stiff spine. Over time, many of the pages cracked and tore.

Recreation of a Colonial bookbinder from the Smithsonian Channel documentary. (Photo by Korin Anderson)

After careful analysis, Janice and Postgraduate Fellows Emily Rainwater and Laura Bedford, and intern Sarah Emerson, decided that in order to conserve the document, it would be necessary to temporarily remove the pages from the binding. Because this was a significant step, Janice consulted with Michael Suarez, S.J., director of the Rare Book School at the University of Virginia, who concurred in the decision. Smithsonian Libraries scanned each page, and Janice and her team documented the volume’s current condition, created a glossary of terms for future generations to consult, and carefully performed and recorded each repair.

The Museum Conservation Institute analyzed 12 different kinds of paper in the Jefferson bible and quantified the vulnerabilities of each material. Because there were so many materials, one solution often complicated a separate problem, so the team ruled out some treatment options.

Unveiling our National Treasure

The Jefferson’s Bible exhibition at NMAH’s Albert H. Small Documents Gallery will be open from November 11, 2011 to May 28, 2012. Visitors will see the newly conserved volume, along with two of the source books Jefferson used, and an original copy of the 1904 printing that Congress requested with an introduction by Dr. Adler. This printing began a tradition of providing new members of Congress with a copy of the Jefferson Bible that was followed for nearly 50 years.

If you would like to read the Jefferson Bible in its entirety, Smithsonian Books will release a first-ever, full-color facsimile in November. Smithsonian Books worked closely with Marie Koller, pre-press manager for Smithsonian Media, and NMAH to make this book project a success.

Next year, the Smithsonian Channel will air a documentary covering the behind-the-scenes conservation treatment, and how and why the Jefferson Bible was created. Filmed at NMAH, Jefferson’s home Monticello, the University of Virginia he founded in 1819, and a bookbinding shop in Williamsburg, the documentary captures Jefferson’s personality, and explores many of the challenging questions occupying his mind. For airdate information, visit smithsonianchannel.com.

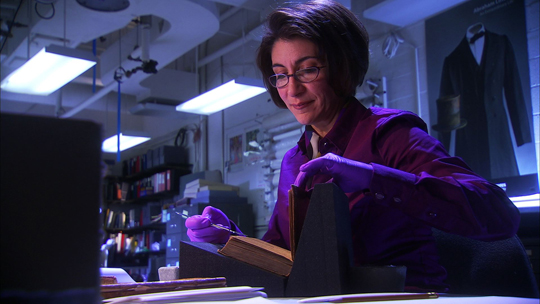

Janice Stagnitto Ellis, paper conservator at the American History Museum, carefully analyzes the Jefferson bible in the Smithsonian Channel documentary. (Photo by Rob Lyall)

As author of the Declaration of American Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, Thomas Jefferson is one of our most well-known Founding Fathers. Yet, few of Jefferson’s contemporaries were privy to a project he found intensely personal and important. The Jefferson Bible is an insight into one of the greatest minds our nation has created, and I am delighted we are sharing this one-of-a-kind book with Americans and the world.

Posted: 16 August 2011

- Categories: