In the dark, it all matters

Like all galaxies, our Milky Way is home to a strange substance called dark matter. Dark matter is invisible, betraying its presence only through its gravitational pull. Without dark matter holding them together, our galaxy’s speedy stars would fly off in all directions. The nature of dark matter is a mystery—a mystery that a new study has only deepened.

“After completing this study, we know less about dark matter than we did before,” said Matt Walker, a Hubble Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and lead author of the paper accepted for publication by The Astrophysical Journal.

The standard cosmological model describes a universe dominated by dark energy and dark matter. Most astronomers assume that dark matter consists of “cold” (i.e., slow-moving) exotic particles that clump together gravitationally. Over time these dark matter clumps grow and attract normal matter, forming the galaxies we see today.

Cosmologists use powerful computers to simulate this process. Their simulations show that dark matter should be densely packed in the centers of galaxies. Instead, new measurements of two dwarf galaxies show that they contain a smooth distribution of dark matter. This suggests that the standard cosmological model may be wrong.

“Our measurements contradict a basic prediction about the structure of cold dark matter in dwarf galaxies. Unless or until theorists can modify that prediction, cold dark matter is inconsistent with our observational data,” Walker stated.

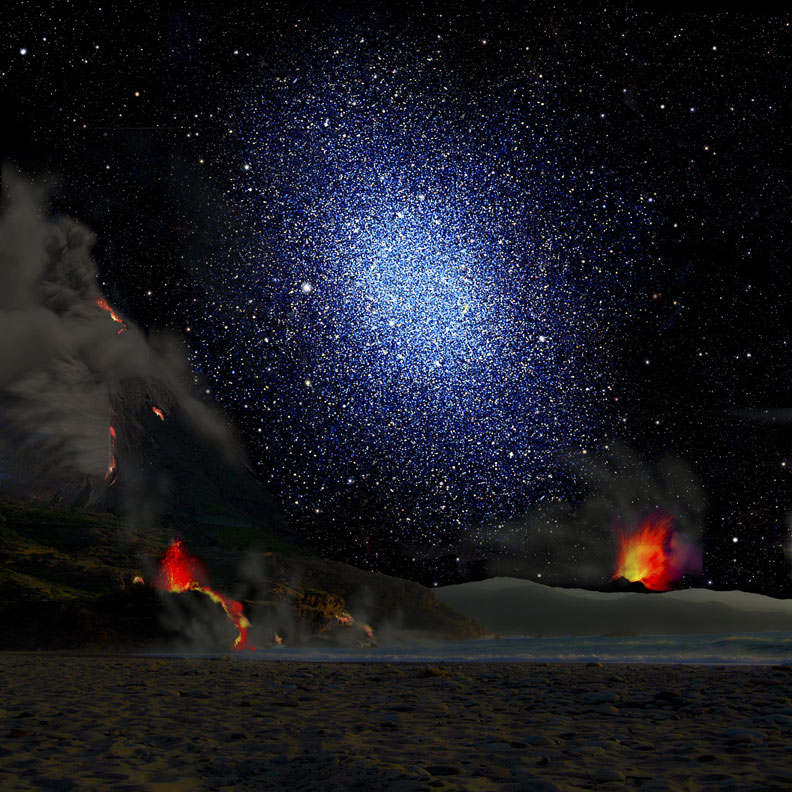

This artist's conception shows a dwarf galaxy seen from the surface of a hypothetical exoplanet. A new study finds that the dark matter in dwarf galaxies is distributed smoothly rather than being clumped at their centers. This contradicts simulations using the standard cosmological model known as lambda-CDM. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

Dwarf galaxies are composed of up to 99 percent dark matter and only one percent normal matter like stars. This disparity makes dwarf galaxies ideal targets for astronomers seeking to understand dark matter.

Walker and his co-author Jorge Penarrubia (University of Cambridge, UK) analyzed the dark matter distribution in two Milky Way neighbors: the Fornax and Sculptor dwarf galaxies. These galaxies hold one million to 10 million stars, compared to about 400 billion in our galaxy. The team measured the locations, speeds and basic chemical compositions of 1,500 to 2,500 stars.

“Stars in a dwarf galaxy swarm like bees in a beehive instead of moving in nice, circular orbits like a spiral galaxy,” explained Penarrubia. “That makes it much more challenging to determine the distribution of dark matter.”

Their data showed that in both cases, the dark matter is distributed uniformly over a relatively large region, several hundred light-years across. This contradicts the prediction that the density of dark matter should increase sharply toward the centers of these galaxies.

“If a dwarf galaxy were a peach, the standard cosmological model says we should find a dark matter ‘pit’ at the center. Instead, the first two dwarf galaxies we studied are like pitless peaches,” said Penarrubia.

Some have suggested that interactions between normal and dark matter could spread out the dark matter, but current simulations don’t indicate that this happens in dwarf galaxies. The new measurements imply that either normal matter affects dark matter more than expected, or dark matter isn’t “cold.”

The team hopes to determine which is true by studying more dwarf galaxies, particularly galaxies with an even higher percentage of dark matter.

(Editor’s note: The 2011 Nobel for Physics is shared by astronomers Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt and Adam Riess—the first to observe the increasing expansion of the universe over 20 years ago, when the light from distant supernova were weaker than expected.

After coming to the conclusion that this meant the universe was expanding faster, they have been in the forefront in the continued study of dark energy since then.

In presenting the Nobel Prize to the group, the Academy stated that their work has “helped to unveil a universe that to a large extent is unknown to science. And everything is possible again.”)

Posted: 19 October 2011

-

Categories:

Astrophysical Observatory , Feature Stories , Science and Nature