“Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello will present “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty,” an exhibition of artifacts from the Smithsonian’s collections and from excavations at Jefferson’s Virginia plantation. The exhibition will be on view in the NMAAHC Gallery in the National Museum of American History from Jan. 27, 2012 through Oct. 14, 2012.

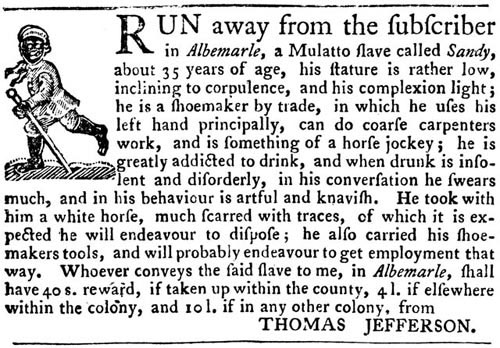

Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence and called slavery an “abominable crime,” yet he was a lifelong slaveholder. An age inspired by a revolution for freedom and independence was also a time of slavery. Twenty-eight percent of the American population was enslaved in 1790.

The exhibition will provide a rare and detailed look at the lives of six slave families living at Monticello—the Hemings, the Gillettes, the Herns, the Fossetts, the Grangers and the Hubbard brothers. Visitors will come to know these families through personal belongings and working tools, including scythes to cut wheat, axes, wheel jacks used to replace a wagon wheel, stoneware jars and carpentry tools as well as tableware, children’s toys and accessories such as shoe buckles. In addition to the physical objects, the research gives a record of the families’ connections to one another, their religious faith and their efforts to pursue literacy and freedom.

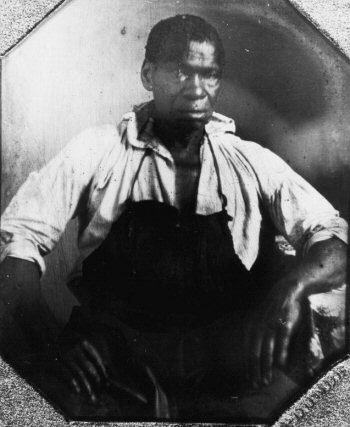

Isaac Jefferson, also likely known as Isaac Granger (1775 – ca. 1850) was a valued, enslaved artisan of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson; he crafted and repaired products as a tinsmith, blacksmith and nailer at Monticello. Although Thomas Jefferson gave Isaac and his family to his daughter Maria and her husband John Wayles Eppes in 1797 as a wedding gift, Isaac Jefferson/Granger appeared to gain his freedom by 1822, according to his memoir. In the 1840 census he was recorded as Isaac Granger, a free man working in Petersburg, Virginia.

“Understanding the details of the lives of enslaved people adds to our understanding of history and our understanding of race relations today,” said Lonnie Bunch, director of the museum. “We cannot have a clear view of Jefferson, or the founding of our nation, if we leave slavery out of the story.”

“As a result of Jefferson’s assiduous record-keeping, augmented by 50 years of modern scholarly research, Monticello is the best-documented, best-preserved and best-studied plantation in North America,” said Leslie Greene Bowman, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. “Through our partnership, Monticello and the Smithsonian have a unique opportunity to discuss slavery as the unresolved issue of the American Revolution and to offer Jefferson and Monticello as a window into the unfulfilled promise of ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’”

A focal point of the exhibition will be archeological artifacts that belonged to enslaved families at Monticello. Among the objects will be:

- Jefferson’s portable desk, made by Benjamin Randolph, Philadelphia, 1776, on which he wrote a “rough draught” of the Declaration of Independence (from the National Museum of American History collection)

- Ceramic tableware and wine bottles from Shadwell, the tobacco plantation of Jefferson’s parents, later named Monticello by Jefferson

- The headstone of Priscilla Hemmings (Sally’s sister-in-law and nursemaid to Jefferson’s grandchildren, ca. 1776–1830)

- Bill of sale for a “negro girl slave named Clary,” for 50 pounds (from the NMAAHC collection)

- Cast-iron cooking pot and kitchen utensils from Mulberry Row (the road encircling the Monticello house). Jefferson provided each family with weekly rations of cornmeal, pork or pickled beef and four salted fish, which had to be supplemented with the food that the enslaved families grew

- Personal items from slaves such as toothbrushes made with bone handles, combs, metal buttons and shoe and clothing buckles and jewelry

- A mahogany chair (ca. 1817), a copy of the French chairs in the Monticello house and a hanging cupboard (ca. 1820) probably made by John Hemmings

“Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty” is presented NMAAHC in partnership with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. The exhibition is co-curated by Rex Ellis, associate director for curatorial affairs at NMAAHC, and Elizabeth Chew, curator at Monticello. Objects in the exhibition come from Monticello and two Smithsonian museums—African American History and Culture and American History.

Thomas Jefferson Foundation was incorporated in 1923 to preserve Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson in Charlottesville, Va. Monticello is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a United Nations World Heritage Site.

Ed. Note: The Hemings family members spelled their name with one or two “m”s. The Smithsonian and Monticello use the spelling that the individuals used. If there is no record, the single “m” is used.

Posted: 15 November 2011