On the Road in Peru: The Secretary’s travel journal

October 4 – Machu Picchu. Weather: warm with clouds, hazy sunshine

Machu Picchu is a fabled Inka site conceived during the reign of Pachacutec, with construction beginning around 1450 and continuing even after the Spanish conquest. It is perched atop a sloping plane surrounded by high mountain peaks, the closest being Huayna Picchu to the north and Machu Picchu to the south. The Inka Road connected Machu Picchu to Cusco via a three- or four-day walk. A network of trails linked Machu Picchu with other cities and religious sites, many of which have only been uncovered in recent times.

Machu Picchu was abandoned in the mid 1500s when the Spanish completed their suppression of the rebellions by Manco Inka and his sons. There is debate as to whether the Spanish knew about Machu Picchu, but it is hard to imagine they did not. Over the centuries, local descendents of the Inka farmed the area and there are indications that one or more Europeans visited it. In 1911, 100 years before our visit, a Yale Professor, Hiram Bingham, undertook an expedition to find and document Inka sites, and in the course of his work, visited Machu Picchu based on advice from local sources. When Bingham found the site, its buildings and grounds were largely overrun by the surrounding jungle. He spent only a day there, but took photographs and explored the area. He recognized that this was an exceptional find and returned in a later expedition to formally document the site and collect artifacts. While it cannot be said that Bingham discovered Machu Picchu, his revelation of its existence created worldwide interest in it and the accomplishments of the Inka people.

Because most things of value had been removed by the Inka or looted over time, Bingham’s collections from Machu Picchu were mainly of pottery and ordinary items of everyday life. The collections were taken to Yale University and ultimately became the subject of a lawsuit about their return. An agreement was made to return the artifacts to a museum in Cuzco, which, ironically, would open on the day of our scheduled return to Lima.

Over time, large segments of Machu Picchu have been cleared so that today it can accommodate tourists who come from all over the world. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1983. Our visit begins with a train that leaves Cuzco early in the morning and takes us on a route that follows the Urubamba River.

Carefully engineered terraces allow agricultural use of the steep mountainsides. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

The train’s observation cars allow us to see the vistas afforded by the mountains and fertile valleys. Inka engineering is on full display all along the route in the form of walled terraces that climb successively higher up the valley walls, allowing for much expanded agriculture in the valley. It is not only the size and number of these terraces that are impressive but also their grace as they flow with the contours of the valley. Behind each of the rock walls lies a remarkable drainage system that collects water so that it flows to a designated outlet, thus preventing the water from eroding the foundation or building up behind the wall. Along the way, there are also places where the Inka built walls to channel the river so its water could be effectively used to irrigate the crops and to prevent the channel from shifting and undermining the walls.

The town of Aguas Calientes is the starting point for the trip to Machu Picchu. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

High above the valley floor we often catch sight of the Inka Road itself, which is located near the top of the mountains surrounding the valley. Today, hikers enjoy using the road, traversing it from Cuzco to Machu Picchu in a three-day trek.

After an enjoyable ride almost entirely downhill we arrive in the small a picturesque town of Aguas Calientes in the valley below Machu Picchu. The town is host to a number of small hotels and a veritable village of shops full of Inka toys, textiles and knick-knacks. A riotous creek runs through the northern side of the town creating a beautiful water feature.

We catch a bus to carry us up to Machu Picchu and the ride over bumpy winding dirt roads is not for the faint of heart. A well built welcome center with ample restaurant facilities provides our kick- off point for a short walk to Machu Picchu.

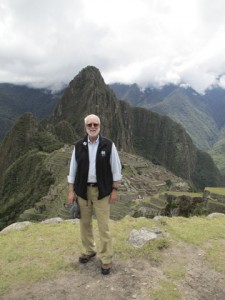

Much has been learned about Machu Picchu over the past hundred years and our guide, Roger Valencia, is well versed in all of the research. He has planned our visit so that in the morning we explore the outer sections of the site to avoid the congestion that can occur in the central areas. Reaching the upper ridge line overlooking the site, we take our time to enjoy the view. From here we explore one of the trails built to bring people from areas to the west of Machu Picchu. It is an engineer’s delight, hugging the side of a mountain, in some places seemingly glued to the rock face itself. The Inka mastered a technique in these circumstances to cut rock out from the face along joints, creating a ledge that supports the trail.

After we return to the main site, we partake of a welcome lunch at the visitor’s center. As Roger has predicted, after lunch, the majority of the tourists board buses to take them back down to Aguas Calientes, giving us an unhurried and uncrowded afternoon to spend in the central area of Machu Picchu. Roger walks us through the areas designed for food storage, living quarters, religious ceremonies and astronomical observations. It is remarkable that Machu Picchu is so intimately designed to link to all that the Inka honored and worshipped. Nothing is there as a matter of chance.

It is believed today that the site was chosen by Pachucutec Inca to serve as a retreat, but that it also contained religious and sacred facilities. As was the custom for Inka leaders, even after his death, Pachacutec Inka was revered by the presence of his mummy. Ever conscious of astronomy and the importance of connections, the site lies in a direct line between the peaks of Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu, forming a direct line back to the Sun Temple at Cuzco. There are other remarkable alignments between the temples at Machu Picchu and surrounding mountain peaks. Windows in the temples were located to capture the sun’s rays on the days of the summer and winter solstices. It is said that on such occasions, a gold statue of Pachacutec Inka standing in the temple chamber would be illuminated as the sun’s rays crept into the chamber with gold light reflecting out into the courtyard.

The Inka graced Machu Picchu with flowing terraces, and buildings and iconic features that draw strength from the surroundings and in some cases, incorporate large sculpted boulders into the structures themselves. What we see of it today is only a small portion of what it was, and we know more remains to be discovered. Every peak surrounding the site has steeply winding stone stairs ascending to religious shrines on the top to allow for sacrifice and offerings. Machu Picchu is an architectural monument, but also an engineering marvel. The terraces that cling to the steep slopes provide erosion protection during the heavy rainfall that occurs each year. Water channels are woven into the fabric of the walls and structures to control flow and provide water where needed. The designs of the structures are the work of master engineers who were advanced for their time. In recognition of this accomplishment, Machu Picchu was designated as an Engineering Heritage Site by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Machu Picchu is graced with flowing terraces, buildings and iconic features that draw strength from their surroundings and in some cases, incorporate large sculpted boulders into the structures themselves. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

There are many mysteries about Machu Picchu and one of them is how it was built in such a remote site on top of a mountain that requires a thousand-foot climb to reach it. No one knows for sure, but there is growing evidence it was accomplished relying on a well established approach to public service. This was known as the mit’a system, where Inka citizens were expected to provide a portion of their time each year in military service or in working on major public works projects. In the case of a site like Machu Picchu, citizens with needed skills would have been expected to work as a matter of their commitment to the state for some period of time after which they would return home. This was an ingenious way to create a labor pool and avoid the need to use permanent slave workers.

Today, only the walls remain of the structures of Machu Picchu. Researchers believe that In its days of glory the structures were covered by plaster and painted in bright colors such as those found in Cuzco and elsewhere.

We conclude our stay in Machu Picchu by taking the bus down to the train station and boarding a train for a trip that will conclude well short of Cuzco at the town of Ollantaytambo, an important city for the Inka leaders. For a time it served as a new capital for the Inka after the Spanish took over Cuzco from them. From Ollantaytambo, we take a van to an overnight accommodation which affords us a view of the Urabamba River. Little time is available for the view however as we arrive late and have to leave early the next morning. Our departure is made more festive by the arrival of several alpaca, smaller cousins of the llama. These fellows are about waist-high with beautiful brown eyes and pleasant personalities, making for a delightful sendoff.

October 5–The Sacred Valley. Weather: Cool and comfortable with abundant sunshine.

Today is devoted to travels though the Sacred Valley, a wide alluvial deposit formed by the deposition of soil from the high mountains that rise up on either side of the valley. The Urubamaba River meanders through the valley carrying meltwater derived from the glaciers of the Andes. The river sustains the ecosystem of the valley, and by flooding, nourishes the fertile soil that so readily grows crops for the people.

The name Sacred Valley comes from a concept held by the Andean people and refined by the Inka, about the cycle of water. Water originates in the mountains, flows down through the valley, giving life, and continues down to the lowlands and jungles before it emerges at the ocean, where it rises in the form of clouds that return as rain in the mountains. The valley is sacred because it is central to the water cycle and that is what sustains life. Climate change may be threatening the vitality of the cycle as the glaciers that normally feed Peru’s rivers melt more rapidly.

Our trip begins early and takes us along the main road in the valley, running through a string of small farming villages. It is a busy time as families are getting their children off to school with transportation provided by vans and an endless procession of rickshaw-like vehicles powered by small motorcycles. Women are dressed in very colorful clothes and often wearing what appear to be men’s hats. Roger informs us that what we see as “Inka style” is actually a hybrid of Inka and 19th-century Spanish styles. After the Inka rebellion, the Spanish overlords decided that Inka culture should be repressed. They outlawed Inka religious ceremonies, speaking Quechua and wearing Inka dress. As a result, the native people were required to adopt 19th-century Spanish clothing. As time passed, they transformed the European styles with the distinctive bright colors favored by the Inka.

Our first stop is Yucay, the home of Sayri Tupa, the son of Manco Inka, who led the failed rebellion against the Spanish and was assassinated for his efforts. Sayri Tupa was spared by the Spanish and lived peacefully as the leader of the Inka in Vilcabamba, the city founded by his father. In 1560, the Spanish viceroy persuaded Sayri to forgo his title as leader of an independent state and to leave Vilcabamba. In return, he was given the title of Prince of Yucay along with a great estate. His sudden death in 1561 led many to believe he was poisoned by the Spanish.

From Yucay we travel to Pisac, an attractive city surrounded by high mountains and the rich soil of the Sacred Valley. Pisac is home to a thriving market for products made by the native people and is attracting a growing number of tourists. It is also home to a new museum, the Museo Communitaro de Pisac, designed with the help of the Smithsonian and our two travelling companions, Ramiro Matos and Jose Barreiro. We are greeted enthusiastically by the staff of the museum, all of whom are clearly proud of this new facility. As we enter, the staff showers our heads with white rose petals, a sign of good luck.

Many of the artifacts in the museum are gifts from local people. The exhibits demonstrate the outstanding craftsmanship of local textile weavers and the nature of the region’s agriculture. A number of exhibits describe the civilizations that existed in ancient times, including the Inka.

The museum tour is followed by a time for refreshments made from local products, including cheese and corn. Each member of our party is given a gift in thanks for what the Smithsonian has done for the community. Mine was a wonderful hand-woven vest that was made by a local craftswoman. Short remarks are made thanking each person. The graciousness of our hosts is heartwarming and I do my best to thank them. Brenda Pipestem speaks with passion about the importance of the work being done to support the Quechuan culture and bring it back so future generations can see what has been lost to earlier generations.

From left, Secretary Wayne Clough, Washington Camacho, mayor of Pisac and Kevin Glover, director of the National Museum of the American Indian. (Photo by Ramiro Matos)

From the museum we are invited to join the Mayor of Pisac, Washington Camacho, in his office. He speaks eloquently about the positive impact the Smithsonian and NMAI have had on the town through our collaboration on the new museum. Kevin Gover and I are each presented with a handmade Inka staff of governance. The staff is made of wood and bound in several places with silver. I am looking forward to using mine at an upcoming Smithsonian meeting.

After a morning of remarkable hospitality we depart from Pisac and head up the mountains to Chawaytiri, a small community of Quechua families known for their fine weaving and colorful dyed textiles. The village is located at 12,500 feet on a plateau of rolling hills. Llamas graze the fields and potatoes are the primary agricultural crop. Historically, the people have had a long interdependence with the llama, with the llama serving both as a pack animal and a source of meat. Ramiro and Jose have worked with the people of Chawaytiri for many years, learning to appreciate their culture and ways, and helping them by bringing their woven products back to NMAI for sale with the proceeds returned to the people.

Our rendezvous point lies along a highway bounded on one side by a cultivated field and on the other by a gentle downward slope that levels out against a sharply rising rocky hill towering over the landscape. Greeting us there is a gathering of native people clad in brightly colored clothing. As we step out of the van the joyous sound of flutes and drums reach our ears and we are encouraged to follow the music makers down a well trodden path towards the valley floor. I am informed the path we are following is indeed the Inka Road, and the people who have met us call themselves the “People of the Llama,” a title showing the great respect that is held for the llama. These are descendents of the Inka people and we are on our way to a site considered sacred to them and their ancestors. We are walking through history, one that includes not only the Inka Road, but also the nearby remains of a way station once used by the fabled Inka runners who carried news across the empire. But the history of this place goes back thousands of years before the Inka, as we will see when we hike up the hillside.

As we reach a level area at the base of the hill we are greeted by male dancers wearing headdresses adorned by bright orange feathers that once belonged to macaws in the Amazon. Assembled with them and herded by a group of women are 20 or 30 llamas. We are treated to a series of dances before the head of the clan gives us a hearty welcome. I learn that my title in Quechuan is “Great Chief of the Smithsonian.”

After some time I am asked to come forward; the clan leader gives me his fluted wooden staff, sharpened on each end. Ahead of me is an arbor made of tree limbs with a beer bottle hanging in the middle of the arch. Ceremony requires that I break the bottle with the staff before we can proceed through the arbor. Fortunately, I am a bit of an old hand at this, having christened new shells for the Georgia Tech crew team. The key is striking a hard blow in the center of the bottle where it is the weakest. In boat christening it is bad luck to strike the bottle and not break it, and I assume this applies here, so I give it my best shot with resounding success, as the bottle breaks cleanly and I am cheered by the onlookers for a job well done. I am showered with rose petals several times for good luck and we step briskly through the arbor to follow a small path up the hill.

We are escorted by the dancers and others from the greeting party. It does not take too long for the lowlanders to feel the impact of the exertion at this high elevation and we stop from time to time to rest. Our destination is a spot well up on the hillside where a rock outcropping occurs. On the outcropping are ancient pictographs of llamas and other figures. I am told these date back at least 2,000 years and earlier, representing a holy place for the People of the Llama and one where they can commune with the memory of their distant ancestors.

Returning down the hill to the gathering of the llamas, more dancing ensues and no one is allowed to be a wallflower. Several young women grab me by the hand and do their best to coax out some rhythm from their poor student. Many of the llamas move up to the dance perimeter to see what is going on, probably wondering who these new people are.

When the time comes to move on, we line up in a procession so that as a group we follow in the tracks of the llamas, walking slowly and savoring the moment–one that may never come again. The procession takes us down to the community center, which serves as a gathering place and an open air market for the people to sell their woven textiles. A hearty lunch is prepared consisting of broiled chicken, potatoes and a local delicacy, guinea pig or cuy. Guinea pigs are both a food source and a pet for the homes of Quechuans. I enjoyed the lunch, although I have to admit I prefer guinea pigs as pets far more than as food.

Before we leave, many of us purchase textiles from the people in the market. Several weavers demonstrate how they dye the fabric with different colors made from native materials. It is an oddity that the brightest red comes from boiling died insects.

As we part, the clan leaders assemble the group and speak with emotion about their appreciation for the work of Ramiro and Jose and their admiration for the Smithsonian. Each member of our party is given a present, a work of the local weavers. Mine is a cloth with beautiful colors and symbols that represent sacred icons for the Quechuans, the sun and coca leaves. We all express our thanks for a memorable afternoon and regret having to leave. As we rise each person is hugged by every other person and more rose petals are showered on our heads as a way of saying goodbye. The musicians begin to play and we are invited to dance our way to the van. As the van pulls away we watch as our new friends wave until we are out of sight.

October 4 – Return to Cuzco.

The return to Cuzco requires a re-boot of the brain. We have left a world that resides in another time, and return to a cosmopolitan city that combines the modern and the ancient. After a brief rest, we convene for a collegial dinner with a group of Cuzco residents who are engaged in one way or another in the Inka Road project. Principal among them is Susana Baca, the Minister of Culture for Peru, who, in spite of having just returned from a tiring trip to Korea, makes time to join us. Minister Baca is in her own right a world renowned singer and performer, but has chosen to serve as Minister of Culture as a matter of public service. She is in Cuzco to celebrate the opening of an exhibition of artifacts collected by Hiram Bingham at Machu Picchu that have recently been returned to Peru by Yale University.

October 5 – Return to Lima. Weather: warm with sunshine.

Flying back to Lima signals our intention to return home, but first we have important diplomatic duties. We are privileged that the American Ambassador to Peru, Rose Likins, is hosting a lunch for us at the Embassy with key members of the Peruvian government and the Lima business community. A prolonged reception allows us to personally meet many of the guests. Ambassador Likins is an ideal host and provides me with time to speak to the guests about the Smithsonian and our goals for the Inka Road exhibition. Near the conclusion of the lunch, Minister Baca joins us. Ambassador Likins’ hospitality allows us to identify a number of contacts who we hope will help provide support for the Inka Road exhibition.

Secretary Clough and Minister of Culture Susan Baca with a signed Memorandum of Understanding between the Smithsonian Institution and the nation of Peru. (Photo by Ramiro Matos)

We proceed with Minister Baca to the National Museum of Peru, where we will sign a Memorandum of Understanding between the Ministry of Culture of Peru and the Smithsonian. The MOU expresses our intent to work collaboratively in a broad range of areas such as museology and collections and to use our joint efforts to bring the Inka Road exhibition to fruition. Minister Baca and Ambassador Likins join me in a press conference where we share our views on the value of our plans for collaboration and how this will benefit both Peru and the United States.

The signing concludes the activities expected for our visit and we head out to the airport for the late flight that will bring us overnight to Miami the next morning. The trip has had a full agenda, but it has been packed with memorable moments. My introduction to ancient culture of the Inkas and the warmth of their descendants leaves me looking forward to the Inka Road exhibition with great anticipation.

(Read Part 1 of One the Road in Peru here.)

Posted: 12 December 2011

Dear Mr. Secretary,

A brief request or suggestion would be that you have someone along, this Peru trip would have been ideal, to take .wav video clips to add to your articles.

Odds are very good that I will not be going to Inka sites. I learned much from your story, which I found well-written for non-engineers, in the vein of Stephen Jay Gould’s articles in Natural History Magazine years ago, scholarly while of generous spirit.

Anyhow, a couple of panoramics of those mountains would have been terrific.

Best,

Tony