Sackler Gallery premieres “Masters of Mercy: Buddha’s Amazing Disciples”

In early 1854, just as American Commodore Matthew Perry’s ships steamed into Edo Bay to persuade Japan to open its ports to the world, the esteemed painter Kano Kazunobu (1816-63) received a commission from a highly respected Buddhist temple located in the heart of Edo, now modern-day Tokyo. His mission was to create 100 paintings on a wildly popular theme of the day—the lives and deeds of the Buddha’s 500 disciples, known in Japan as rakan.

For the first time in the U.S., Kazunobu’s graphic and flamboyantly imagined depictions of the daily lives and wondrous deeds of the Buddha’s legendary disciples are on view in “Masters of Mercy: Buddha’s Amazing Disciples” at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, March 10 through July 8.

Kano Kazunobu (1816–63) Japan, Edo Period, ca. 1854–63 Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk Collection, Zōjōji, Tokyo

Right: According to the Lotus Sutra, humans may escape the seven misfortunes of fire, wind, floods, wars, punishments, demons, and thieves by reciting the name of Kannon, goddess of mercy. Here, it is the rakan who are brought to the fore, shown making various gestures of compassion while the diminished bodhisattva virtually recedes into the inky background.

Below, people scramble out from under collapsed buildings and fallen trees, as spear-like flames threaten to engulf them. The debris of destroyed lives is detailed with compelling realism.

The Great Ansei Earthquake of November 11, 1855, devastated the city of Edo shortly after Kazunobu began working on the set. Firsthand experience of the catastrophe no doubt informed Kazunobu’s painting, as did the numerous prints and book illustrations produced in the aftermath.

At the time of the commission, Kazunobu was a mature and important painter working in one of the richest artistic environments of any era in Japan, among several generations of artists of remarkable sophistication and accomplishment. For his larger-than-life subjects, he created huge paintings measuring 4 feet by 10 feet fully mounted. Designed in pairs, each pair features 10 disciples—500 in all—captured in a sensational and daring “tabloid” style.

The exhibition features 56 paintings from Kazunobu’s epic series, created between 1854 and 1863 for the Pure Land Buddhist temple of Zōjōji. Little-known and never before displayed outside Japan, the series was on view for the first time to the modern general public in a widely hailed exhibition held at the Edo-Tokyo Museum in the spring of 2011.

The Sackler exhibition will also include 19 rare and important paintings of the same subject matter from the Freer collection—all prototypes for and known by the artist as he developed his own masterwork. Woodblock prints, books and other documents created by Kazunobu’s contemporaries, including Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), will provide the viewer with a sense of Edo period ambiance and influences on Kazunobu’s unconventional presentations.

“Kazunobu jumped on the bandwagon of the most popular cult of the Edo period—the cult of therakan or disciples of the Buddha,” said James Ulak, senior curator of Japanese art. “From the late 1700s on, many temples commissioned paintings and sculpture on the subject, often creating outdoor dioramas to accommodate the tremendous public interest in these remarkable characters. In short, Kazunobu’s series is simply the best of them all.”

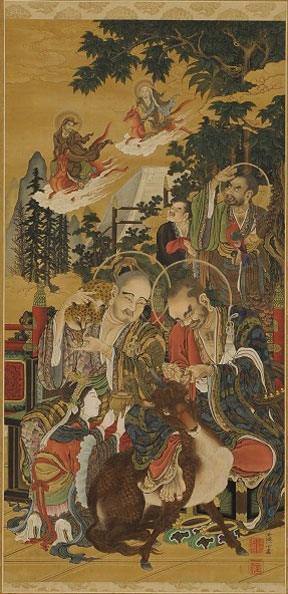

Kano Kazunobu (1816–63) Japan, Edo Period, ca. 1854–63 Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk Collection, Zōjōji, Tokyo

Right: Animals are regarded in Buddhist thought as sentient beings, with capacity for suffering and potential for enlightenment. This section of ten paintings show the rakan engaged with a variety of animals, both real and mythical. In the right scroll, a rakan gently cleans the ear of an animal that appears to be a hybrid of unicorn and deer. Above, two rakan gleefully take a ride on flying red foxes.

The disciples he depicted, according to Buddhist scripture, were followers of the historical Buddha’s teachings, enlightened in mass and traditionally represented by the number 500. “Their charm and broad popular appeal derived from their dual personalities,” said Ulak. “The disciples were much like ordinary mortals, yet they possessed supernatural powers, revealed in times of need and exercised for the good of humanity, not unlike today’s modern superheroes.”

Kazunobu presents the disciples engaged in fantastic acts of compassion: traversing the cosmos to rescue the suffering from the calamities of earthquake, flood and fire, juxtaposed with humbler, human moments revealed in intimate detail—bathing, shaving, burying the dead and caring for animals. His flamboyant style reflects Edo Japan’s broader interest in theatrical presentation, including a popular taste for the high drama of kabuki theater. Depictions of catastrophe and miraculous rescues seem fantastic but also document the times in which he worked—the ensemble was created during a decade of marked political upheaval coinciding with an unusual number of natural disasters.

“Masters of Mercy” is a highlight of “Japan Spring on the National Mall,” a celebration of three major exhibitions of masterworks by distinguished Edo-period artists hosted by the Freer and Sackler galleries and the National Gallery of Art in honor of the Cherry Blossom Centennial.

Also on view this spring is “Hokusai: 36 Views of Mount Fuji,” March 24–June 17 at the Sackler and “Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800),” at the National Gallery of Art.

Each exhibition features not only a retrospective of a distinctive and important painter and designer of the 18th and 19th centuries, but also specific thematic ensembles of works, many never seen outside Japan, created by Kazunobu, Hokusai and Jakuchū over periods as long as a decade. All three exhibitions are free of charge and accessible on the National Mall between 12th and Seventh streets.

Posted: 20 March 2012

- Categories: