NSFW: 50 Shades of…Squid

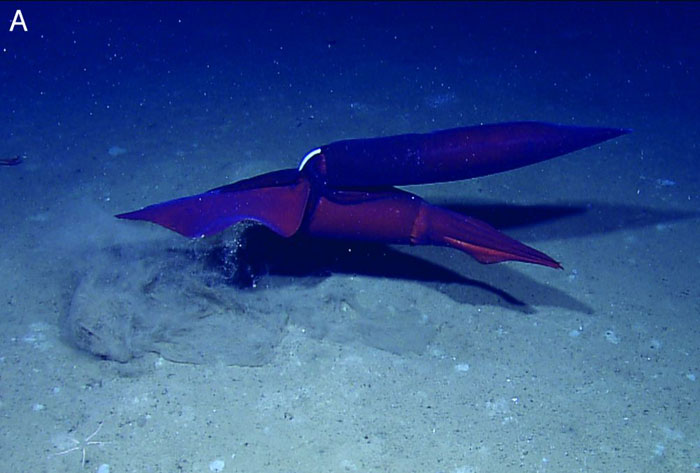

Undaunted by the bright lights of the remote controlled sub filming their activity some 1,400 meters down in the Gulf of Mexico, the two deep-sea squid (Pholidoteuthis adami) maintained their unusual but intimate position. The male was upside down on top of the hovering female, gripping her firmly; their bodies parallel but pointing in opposite directions.

Clearly visible connecting the dark-purple cephalopods is the white “terminal organ” or penis of the male, extending out through the male’s funnel. (A jet-propelled squid forcibly squirts water through its funnel, causing its body to shoot forward tail first.)

Recorded in April 2012, this first detailed observation of the mating behavior of a deep-sea squid species has answered many long-standing questions generated by study of the sexual organs of these creatures in museum specimens. A brief earlier video of the same species recorded in 2006 also contributed to the findings.

“People have guessed how the terminal organ was used, but in some ways they guessed wrong,” explains Michael Vecchione, a research zoologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and co-author of a new paper with H.J.T. Hoving of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, on this behavior in The Biological Bulletin. “We knew the terminal organ was located in the mantle of the male but we didn’t know that it projected through the funnel. The male was upside down, that also was surprising.”

Many squid species use a modified arm, called a hectocotylus, to transfer spermatophores to the female. Others, mainly deep-sea species such as the P. adamisquid in the video and giant squid, have no hectocotylus but use the penis or terminal organ of the male reproductive tract. “Penis is probably a less appropriate name for the organ because it is not homologous with a mammalian penis,” Vecchione says, “but it is used in basically the same way.”

A male squid’s organ emits spermatophores, complex structures containing millions of sperm that turn inside out and attach sperm packages to the female’s body. The sperm then apparently burrow into the female’s tissue.

This image from a video shows a male Pholidoteuthis adami squid above the female, upside down and headed in the opposite direction. The terminal organ is the white elongated structure at center and is seen extending through the male’s funnel. The male has a firm grip on the female with at least three pairs of his arms. Image courtesy NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program.

One thing that surprised pretty much all of the cephalopod people was how long the mating process lasted,” Vecchione adds. “In this species the spermatophores inject sperm deep into the muscle of the female’s dorsal mantle. Because of this we guessed their mating was a really quick process in which the male darts in, shoots the female and then leaves. The video reveals it is a long process where the male is basically hanging on motionless for a long time. They were in that position when we first saw them in the video and they were still in that position when they swam away.”

How sperm implanted in the female’s muscle tissue and skin move to a location in the female’s body where they can fertilize her eggs “is one of the big mysteries of squid life history,” Vecchione says. In the species P. adami the sperm are implanted just outside and above where the eggs come out of the female’s oviduct. “Probably what happens is that the sperm actually burrow through the rest of the dorsal muscle and into the female’s interior mantle to fertilize the eggs as they are coming out. But that’s a guess. We really don’t know.”

Possible reasons for the odd mating positions observed in this squid species, the researchers write, include preventing the female from grabbing and perhaps eating the male, as well as improving mobility of the terminal organ, which would be restricted if the male was not upside down.

The article “Mating Behavior of a Deep-Sea Squid Revealed by in situ Videography and the Study of Archived Specimens,” in the December 2012 issue of The Biological Bulletin was authored by H.J.T. Hoving of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and M. Vecchione of the NMFS National Systematics Laboratory and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Video: This pair of mating Pholidoteuthis adami squid was observed by ROV Little Hercules on April 13 2012 at a depth of 1400 meters during an expedition by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer in the northern Gulf of Mexico. The male is upside down, and backwards on top of the female and the terminal organ is extending from his funnel, presumably releasing spermatophores, from which spermatangia burrow into the dorsal mantle tissue of the female. Video courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program.

Posted: 11 January 2013

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature