The wisdom of crowds

Unexpectedly and with breathtaking speed, more than 6 billion cell phones and millions of tablet devices have proliferated worldwide. People across the globe use these devices to pool their knowledge in a revolutionary way known as “crowdsourcing,” doing remarkable things far beyond the capacity of an individual alone. Perhaps the most well-known example of crowdsourcing is Wikipedia. People were initially skeptical of the value of an open-source encyclopedia, but today it provides access to thousands of experts who weigh in on any conceivable topic. The Archives of American Art and SI Archives have had a “Wikipedian in Residence” to help provide accurate information to Wikipedia, and the American Art Museum, AAA and SIA all host “edit-a-thons”—coordinated volunteer efforts to populate Wikipedia with rich Smithsonian content. New technology can fully draw on the wisdom of crowds—a fact that the first Secretary of the Smithsonian, Joseph Henry realized in 1849, making us a very early adopter of crowdsourcing.

Volunteers editing Wikipedia entries at an “edit-a-thon” at the Archives of American Art. (Photo by Effie Kapsalis)

Secretary Henry knew he could take advantage of the telegraph lines that followed the new railroad lines being constructed in our young nation. He enlisted 150 volunteer weather observers to observe storms and other weather occurrences across the nation, a network that would grow to more than 600 internationally. The telegraphed their observations to Washington, where Henry used the collected data to create a weather map. This precursor to the National Weather Service represented citizen science at its best. Enthusiasts would again add to the body of scientific knowledge with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Operation Moonwatch satellite-watching program in the 1950s. Teams of amateur astronomers throughout the country, and eventually the world, were enlisted to watch for artificial satellites during the height of the cold war. Moonwatch participants were the first to give visual confirmation of Sputnik in 1957 and were the ones who enabled Smithsonian scientists to ascertain where it would land. The Operation Moonwatch program ended in the 1970s, but people everywhere are still putting their collective wisdom to work for the Smithsonian in numerous ways, using technology that is exponentially more powerful than the computers that took Apollo 11 to the moon in 1969.

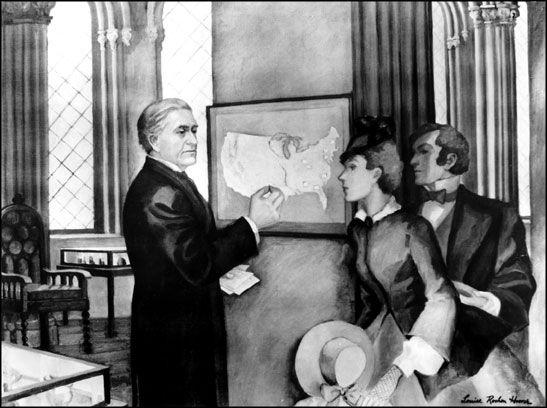

Louise Rochon Hoover’s painting, “Secretary Henry Posts Daily Weather Map in Smithsonian Building, 1858.” Commissioned for the Smithsonian exhibition at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition in 1933.

Social media like Yammer, Facebook and Twitter allow us to increase knowledge by making information a two-way street, whether we communicate with citizen scientists, experts from the Smithsonian, or with external collaborators. For example, Smithsonian staffers identified two pictures of an unknown African American woman from the 38th annual NAACP Conference in 1947 as opera star Carol Brice. Twitter followers recognized the unknown location of a 1937 Archives of American Gardens photo as Chapultepec Park in Mexico City. And external experts helped a team of ichthyologists sponsored by the Natural History Museum to quickly identify more than 5,000 fish specimens they collected in Guyana. To get an export permit, they needed to do this massive task in a short period of time, so they put out the call on Facebook to fellow ichthyologists throughout the world. In less than 24 hours, the collective responses identified approximately 90 percent of the posted specimens, including two that had been unknown.

Kids recording the biodiversity of a stream during a bioblitz in Rocky Mountain National Park. (Image courtesy of National Geographic)

The viral nature of social media empowers data aggregation like never before. Consider the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL), a global repository about life on Earth based at NMNH, which is building a Web page for each of the 1.9 million recognized species. This effort would be impossible without the ability to bring together data from all over the world with the click of a mouse. EOL invites crowds to upload pictures of species using Flickr, provides downloadable field guides to help citizen scientists identify species in their natural habitats, and puts together BioBlitzes—daylong species scavenger hunts for enthusiasts, families, students and teachers. The Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), the scientific literature cornerstone of EOL, is doing its part to use crowdsourcing as well. It has hosted “tagging parties” to train Smithsonian employees to label some of its more than 60,000 Flickr images with identifying metadata. Once tagged with the proper taxonomic information, the images will be much more readily accessible in both the BHL and EOL databases. And our free Leafsnap mobile app, created with the help of Consortium for Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet Director John Kress, is the first to identify tree species from photographs of their leaves. It also allows budding citizen scientists to help build a database of geo-coded species photographs, giving scientists the tools to map and monitor tree populations.

Smithsonian botanist John Kress uses the new mobile app LeafSnap to identify a katsura tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum).

The role of museums is changing and must change if we are to cultivate engaged audiences. When the American History Museum asked participants to vote online for the subject of Robert Weingarten’s next photographic portrait, they chose Celia Cruz—and flipped the relationship between artist and viewer on its head. When NMAH’s American Enterprise exhibit slated for 2015 unveils a new Web portal on March 19 as part of National Agriculture Day, it will invite visitors to upload their stories about farming innovations that fundamentally changed their lives—and will ask them to become virtual citizen curators, changing the dynamic of one of our most fundamental Institutional roles. The National Postal Museum’s ambitious goal is to populate the interactive Web portal Arago with 1,000 new objects each year. By building an online network of expert philatelists in all areas of stamp collection, including 160 volunteers, the museum recognizes what James Surowiecki wrote in The Wisdom of Crowds: “While trusting the collective judgment of the group may be difficult, it’s also smart.”

Recently I had the opportunity to moderate a panel of technology thinkers in collaboration with the University of Maryland and the Future of Information Alliance. The participants have creatively leveraged crowdsourcing to benefit people, from finding earthquake victims in Haiti to using social media and video to expose human rights abuses. As holders of the public trust, the Smithsonian has a sacred duty to use all the tools in our arsenal to allow learners of all ages to access our vast store of knowledge. But for all our historical treasures, brilliant researchers, and talented curators, we recognize that we have to enable people to be active participants in the conversation. Increasingly, the Smithsonian is becoming what author Nina Simon has called “the participatory museum”—a bridge between people who want to tell their stories and those who want to hear them. I encourage all of you to continue to think about ways in which the Smithsonian can use crowdsourcing to allow our visitors to become more engaged, more creative, and more invested in the Smithsonian experience and the issues facing the world today.

Posted: 28 February 2013