Nine deaths, two births

“Nine Deaths, Two Births: Xu Bing’s Phoenix Project”

Contemporary Chinese artist Xu Bing’s massive 12-ton phoenix sculptures arose not from ashes, but from the debris of construction sites in rapidly modernizing China. As the sculptor explains, his creations are “quite different from all phoenixes in history. They can only be produced in the context of globalization.” Xu was originally commissioned to create a piece for the lobby of a Beijing office building. While preparing and conducting research, he was struck by the contrast between the sleek, new buildings quickly going up in China and the harsh living conditions experienced by the construction workers responsible for the growth, many of them migrant workers. Xu’s phoenixes represent the interconnection between labor, rapid development, and wealth.

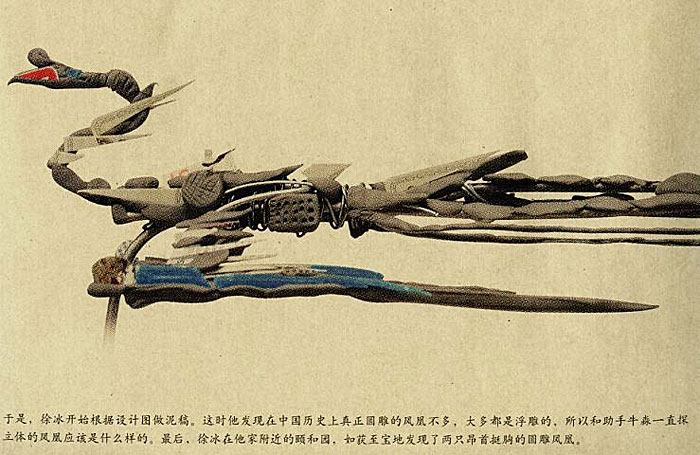

Xu paid multiple visits to a construction site in Beijing’s Central Business District and spent time with the workers, while conducting research on representations of the mythical phoenix in Chinese art. In the resulting sculptures, steel girders, beams, hard hats and other construction materials are recycled to transform a familiar image into a commentary on the dense urban and social contexts prevalent in contemporary China.

The female phoenix, Huang, is 100 feet long, and the male, Feng, is 90 feet long. While the sculptures themselves remain on display at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery exhibition, “Nine Deaths, Two Births: Xu Bing’s Phoenix Project” on view through September 2, documents the project’s development with drawings, technical diagrams, scale models, and a film. The exhibition’s title refers to the highs and lows of Xu’s project, which saw many setbacks (“nine deaths”) but also experienced the celebration of new life—two children born to his studio staff and the phoenixes themselves.

Expected to take four months to complete, the Phoenix Project stretched to two years. It was stalled by the three-month work stoppage ordered by the Chinese government for all construction prior to the before the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijng and the global economic crisis that dried up financial support. Backers in Taiwan eventually came through with funding to complete the project in 2012.

Though Xu notes that the Asian phoenix mythology in which the phoenix represents peace, prosperity and righteousness differs from its Western counterpart as a symbol of rebirth or renewal, the way the project developed shows that in this interconnected world, the global village can prove more powerful than governments or economic crises. Xu’s phoenix sculptures are a testament to the forces of globalization—made in China, financed in Taiwan, exhibited in Massachusetts, their story told at the Smithsonian—and they remind us that our world has never been smaller.

Posted: 14 May 2013

- Categories: