Science for Empowerment: Bringing indigenous people into a global carbon market

(From left) Guna leader Evelio Jiménez, STRI fellow Javier Mateo, STRI research technician José Monteza and STRI associate scientist Catherine Potvin discuss a forest arbon measuring expedition in Diwarsicua, Panama.. The team estimated carbon stocks for comparison with a LiDAR carbon map made by STRI and the Carnegie Airborne Observatory in 2012. (Photo by Sean Mattson)

Evelio Jiménez pilots a canoe through the Guna territory of Madugandí in eastern Panama. The buzz of chainsaws fills the air and timber is stacked on the riverbank. Once the water rises with the rainy season, the lumber will be ferried out. It might appear like another all-too-common scene of deforestation in Panama’s Darién but Evelio says he’s not worried. Commercial loggers will no longer be allowed to operate in the 230,000-hectare territory by 2014, the Guna leader says. He has already moved past timber, anyway. Carbon is his concern.

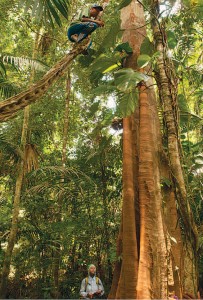

Guna technician Alexis Solis (top) uses a woody vine to reach the trunk of a tree above its buttress roots to measure its diameter. (Photo by Sean Mattson)

On this May expedition in the comarca, Evelio is leading a team of Smithsonian scientists and indigenous technicians who will measure the carbon stores across 30 hectares. The research will generate on-the-ground carbon estimates that will be compared with a carbon map created by Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Carnegie Airborne Observatory. Using Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology, the map is considered the most precise nation-level inventory of carbon stocks to date. But Evelio won’t trust the results until he and colleagues gather ground data and compare it.

“For (the Guna) to believe the results gathered from a plane is just like an act of faith that they are not necessarily ready to do,” explains STRI associate scientist and McGill University professor Catherine Potvin, who is an intermediary between high-end technology and the indigenous understanding of the forested landscape. Her lab, which researches the relationship between carbon stocks and biodiversity in Panama, melds study of the natural environment with the societies of the people who live there. Through two decades of working in Panama’s indigenous communities, the approach—which her students call “Science for Empowerment”—seems to be working. After initial guidance and training, locals maintain long-term conservation science projects.

“This is very important because if this territory wants to engage in a carbon market, for climate change, like payment for ecosystem services…they need to be able to measure carbon, estimate the carbon, monitor the carbon,” says Potvin. Jiménez agrees. If the indigenous leaders decide to enter a carbon market, they will be ready. The Gunas will “have knowledge of how many tons of carbon there are in Madugandí,” he says, proudly.

Posted: 17 June 2013

-

Categories:

Collaboration , History and Culture , Science and Nature , Tropical Research Institute