In memoriam: Theodore Reed

Theodore H. Reed

Theodore Reed, the keeper of the celebrity pandas Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, the playful Komodo dragon Kraken, Smokey Bear himself and thousands of other creatures while he was the director of the National Zoo in Washington from 1958 to 1983, died July 2, 2013 in Milford, Del. He was 90.

The cause was complications of Alzheimer’s disease, said his son, Mark Reed.

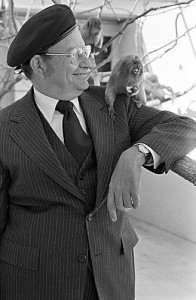

Theodore Reed in 1978 with a golden marmoset at the National Zoo, which he directed from 1958 to 1983.

Dr. Reed, a veterinarian and zoologist, was considered an innovative administrator. He modernized the zoo’s buildings, expanded its role in research and breeding, and employed a ringmaster’s command of spectacle to raise the profile of the nation’s official menagerie.

He was also known for his personal touch. At his suburban home, he helped raise the first white tiger born in captivity, a couple of leopard pups and a half-dozen bear cubs. He leapt into the zoo’s wolf enclosure to save a pup from drowning during a hurricane in 1972. And when the two pandas failed year after year to produce offspring, Dr. Reed adopted the fretting voice of the archetypal in-law in his interviews with reporters.

Looking for someone to blame, he turned to Hsing-Hsing, the male, critiquing his posture and his foreplay technique. “Do you realize what he is doing to the male ego?” he said to a reporter in 1982.

Dr. Reed was an early conservationist among zoo executives. He envisioned zoos as sanctuaries for species threatened by the accelerating development of their natural habitats. But his modestly endowed zoo — the full name of which is the National Zoological Park of the Smithsonian Institution — lacked the financial support for that kind of mission, until the giant panda couple arrived in 1972.

Zoos around the country had competed intensely for rights to the pandas, gifts from China in recognition of President Richard M. Nixon’s visit that year. Despite a tradition of housing animal gifts from foreign countries at the National Zoo, officials at zoos in Chicago, San Diego and other cities argued that they were better equipped to protect and breed the pandas, of which there were fewer than 1,000 worldwide.

But Dr. Reed lobbied hard and won the case for Washington, where negotiating budgets for his publicly financed zoo over the past 14 years had made him an adept navigator of the political terrain.

The pandas, and their subsequent efforts to produce offspring, increased zoo attendance to about two million a year from fewer than a million, made Dr. Reed’s budget negotiations easier and helped him acquire many of the zoo’s less famous but equally endangered animals, including the Komodo dragon, which, in one keeper’s words, proved “as playful as a dog.” Smokey Bear, rescued as a cub from a forest fire in 1950 and acquired after the “Only you can prevent forest fires” public service campaign was in full swing, was designated as the official living version of the campaign’s animated spokesman. He received bags of mail.

The pandas Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing in 1974. The zoo’s attendance grew sharply after the pandas arrived from China in 1972, with their efforts to reproduce drawing widespread attention. (Photo by Charles Tasnadi/Associated Press)

The zoo’s higher profile also helped Dr. Reed argue successfully in 1975 for the use of 3,200 acres of federal land in Virginia to create a new arm, the Conservation and Research Center, which has become one of the premier centers in the country for animal research and for breeding members of endangered species. (It is now called the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute.) Among the representatives of vanishing species there were Mongolian wild horses, scimitar-horned oryxes, maned wolves, red-crowned and white-naped cranes, Bali mynas, black-footed ferrets, clouded leopards, Eld’s deer and cheetahs.

Dr. Reed’s son, who is the executive director of the Sedgwick County Zoo in Wichita, Kan., said the pandas were probably his father’s greatest achievement, as well as his greatest headache. The annual panda mating watch — female pandas are in heat only once a year — became the Groundhog Day of his life, he said.

In 1982, after six or seven years of trying to breed Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, Dr. Reed told a reporter, “I have come to the conclusion that unlike humans, most animals will not breed if they don’t like each other.” The pandas eventually grew friendlier, and Ling-Ling became pregnant five times, though none of the cubs she bore survived for more than a few days.

Theodore Harold Reed was born on July 25, 1922, in Washington, the son of Ollie and Mildred Reed. His father, a lieutenant colonel in the Army, and his older brother, Ollie Jr., were killed in action within two weeks of each other in 1944.

Dr. Reed received degrees in veterinary medicine and zoology at Kansas State College (now Kansas State University) and served as the veterinarian at the Portland Zoo in Oregon for several years before joining the National Zoo as a staff veterinarian in 1955. He was named associate director a year later, and director in 1958.

Besides his son, he is survived by his wife, Sandra Foote; a daughter, Maryalyce Jenkins; three grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

This post by Paul Vitello was originally published by the New York Times on July 7, 2013.

Posted: 19 July 2013

- Categories: