Remembering Gettysburg

After its unveiling in Philadelphia in December 1870, Rothermel’s Battle of Gettysburg: Pickett’s Charge was hailed by many as a masterpiece and a testimony to the horrors of war. Others criticized the painting for its depiction of death and violence, and for opening old wounds between the North and South. Courtesy Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, The State Museum of Pennsylvania/Photo by Christy White

The Smithsonian has been commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War with exhibits, programming, blog posts, television programs and a forthcoming book showcasing the National Museum of American History’s most compelling objects related to the war between the states. Project Assistant Ryan Lintelman reflects on the anniversary of one of its most important but devastating battles in this post originally published by NMAH’s blog, O Say Can You See?.

One of the most noteworthy milestones in this multi-year sesquicentennial of the Civil War is the anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1-3, 1863. The culmination of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of the northern United States, over 160,000 Union and Confederate soldiers met on the field at Gettysburg in a massive battle which changed the course of the war. General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac repulsed the Confederate invasion, shattering the invincible reputation of Lee’s army while inflicting higher casualties, forcing a retreat back in to Virginia, and dashing Southern hopes that European powers might provide military aid.

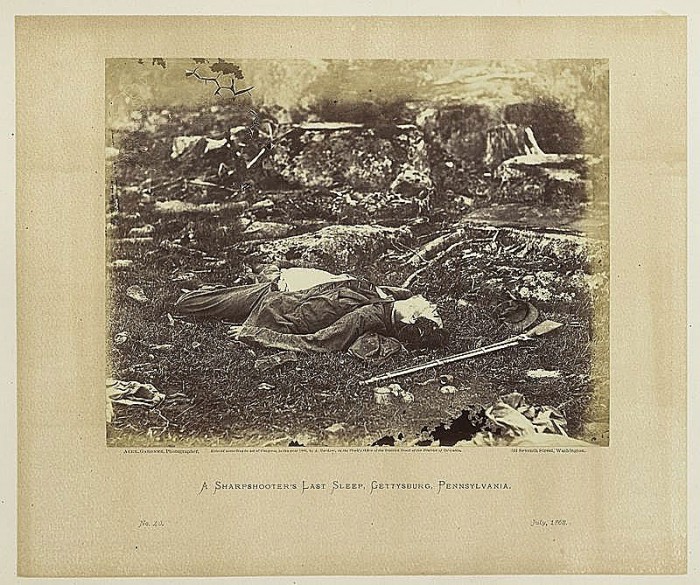

“A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep,” Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from “Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War.”

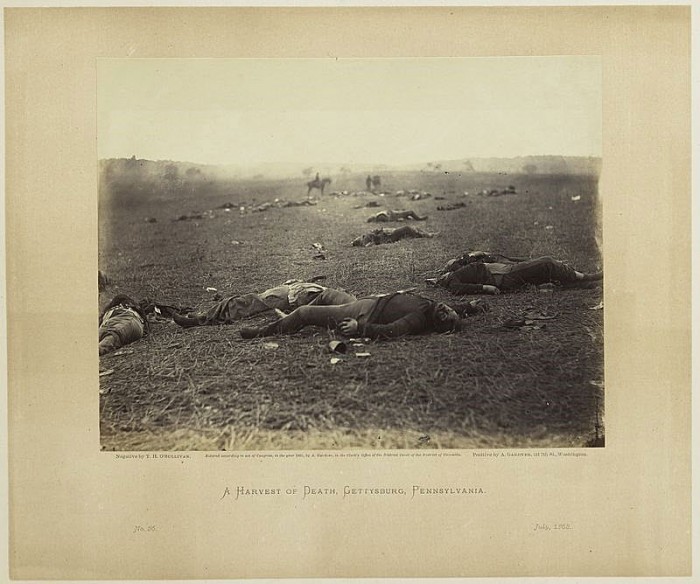

Acknowledged now as a turning point in the Civil War, the only thing that was clear at the time was that it was an unprecedented tragedy in terms of human life. For weeks afterward, Americans pored over descriptions of the fighting, read lists of the more than 46,000 casualties published in newspapers across the country, and viewed gruesome photographs of the aftermath. In the days and weeks following the battle, Alexander Gardner, Timothy O’Sullivan, James Gibson, and Mathew Brady were among the pioneering war photographers who captured some 230 images of the destruction and death surrounding Gettysburg. People hundreds or thousands of miles away from the carnage would see these photos reproduced in illustrated newspapers and magazines, reprinted in publications like Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, or even in their own living rooms if they purchased popular and widely-available cartes-de-visite or stereoviews.

“A Harvest of Death,” Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from “Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War.”

No one knew the horrible toll of the battle better than the men who fought there, including several whose courageous actions made them instant heroes. Recognizing a crucial weakness in the Union line on a hill called Little Round Top, Colonel Strong Vincent ordered his brigade to hold it at all costs. Under heavy fire, Vincent jumped atop a boulder and, brandishing a riding crop, shouted “Don’t give an inch!” just before being fatally wounded in the groin. Before the battle, Vincent had written to tell his wife, “If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.”

Winfield Scott Hancock, who commanded the I, II, III and XI Corps at Gettysburg, bravely rode through the lines to inspire his men during their successful repulse of Pickett’s Charge. When a bullet ripped through Hancock’s saddle, opening an inch-wide hole through his side and groin along with a nail and wood splinters, the general was said to have removed the nail himself, remarking “they must be hard up for ammunition when they throw such shot as that.” Bleeding profusely, he continued to command his men from his stretcher, and would later receive special commendation from Congress. When Hancock returned to Gettysburg in November 1885 the citizens of the town presented him with a case of relics salvaged from the battlefield – pieces of artillery, bullets, belt plates, and other objects engraved with the famous names of the scenes of fierce fighting 22 years earlier.

Case of relics presented to General Winfield Scott Hancock by the people of Gettysburg in 1885. Inscriptions read Cemetery Ridge, Little Round Top, Wheat Field, Railroad Cut, and Culp’s Hill, among others.

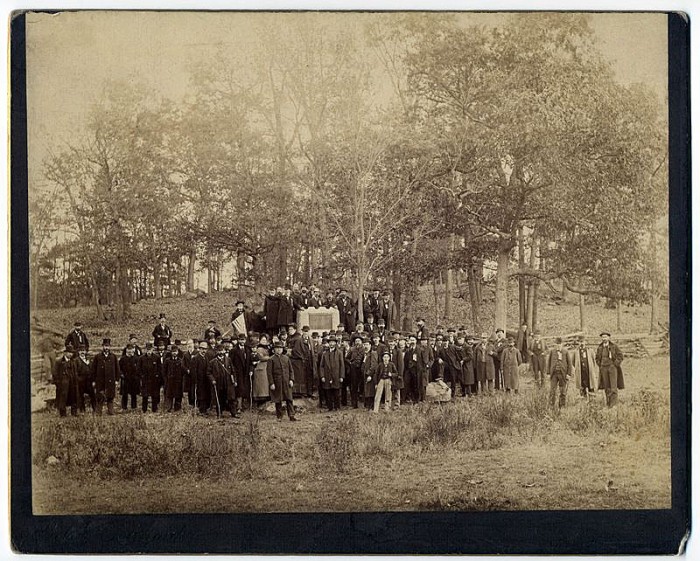

Yet the bravery of these men did not bring a swift end to the war, which would drag on for nearly two more years after Gettysburg. In his Gettysburg Address, a November 1863 speech to dedicate the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, President Lincoln recast the Civil War as a second American revolution, a rebirth of freedom. While the states did reunite in 1865, the Battle of Gettysburg remained a scar on the national psyche. The battlefields of Gettysburg became a site for reflection and remembrance, where veterans built monuments to their fallen comrades and Americans came, as they still do today, to try to make sense of the human toll of the Civil War.

Dedication of a monument on the battlefield at Gettysburg, ca. 1880s. The men gathered around this unidentified monument are probably veterans of the fight. If you can identify this monument, let us know in the comments!

Ryan Lintelman is the Project Assistant for Civil War 150 at the National Museum of American History. For more about the Battle of Gettysburg, read the story of an ambrotype photograph of a woman and child found on the body of a Union soldier after the battle. Guest blogger Brian James Eagan also recounted his experiences as an extra on the set of the film Gettysburg.

Posted: 3 July 2013

This is 2 MA monument. It is southeast of Spanger’s Spring – near intersection of Cosgrove and Carmen Aves.