We are stardust, we are golden–and so is our bling

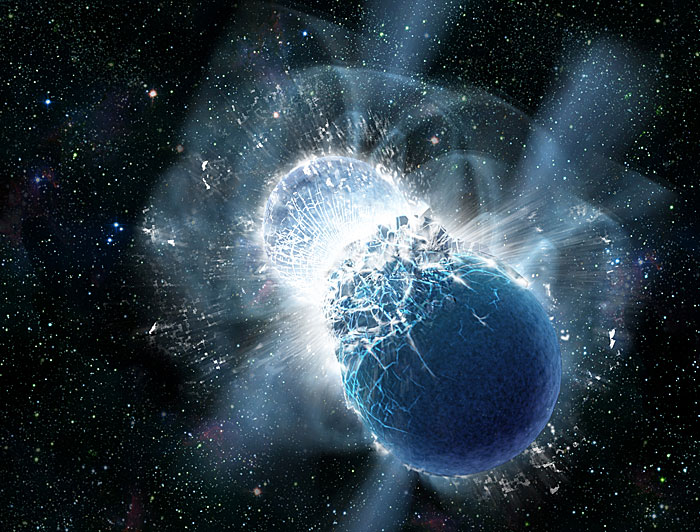

This artist’s conception portrays two neutron stars at the moment of collision. New observations confirm that colliding neutron stars produce short gamma-ray bursts. Such collisions produce rare heavy elements, including gold. All Earth’s gold likely came from colliding neutron stars. (Credit: Dana Berry, SkyWorks Digital, Inc.)

We value gold for many reasons: its beauty, its usefulness and its rarity. Gold is rare on Earth in part because it’s also rare in the rest of the universe. Unlike elements such as carbon or iron, it cannot be created within a star. Instead, it must be born in a more cataclysmic event−like one that occurred last month known as a short gamma-ray burst. Observations of this GRB provide evidence that it resulted from the collision of two neutron stars−the dead cores of stars that previously exploded as supernovae. Moreover, a unique glow that persisted for days at the GRB location potentially signifies the creation of substantial amounts of heavy elements−including gold.

“We estimate that the amount of gold produced and ejected during the merger of the two neutron stars may be as large as 10 moon masses−quite a lot of bling!” says lead author Edo Berger of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

A gamma-ray burst is a flash of high-energy light (gamma rays) from an extremely energetic explosion. Most are found in the distant universe. Berger and his colleagues studied GRB 130603B which, at a distance of 3.9 billion light-years from Earth, is one of the nearest bursts seen to date.

Gamma-ray bursts come in two varieties−long and short−depending on how long the flash of gamma rays lasts. GRB 130603B, detected by NASA’s Swift satellite on June 3rd, lasted for less than two-tenths of a second.

Although the gamma rays disappeared quickly, GRB 130603B also displayed a slowly fading glow dominated by infrared light. Its brightness and behavior didn’t match a typical “afterglow,” which is created when a high-speed jet of particles slams into the surrounding environment.

Instead, the glow behaved as if it came from exotic radioactive elements. The neutron-rich material ejected by colliding neutron stars can generate such elements, which then undergo radioactive decay, emitting a glow that’s dominated by infrared light−exactly what the team observed.

“We’ve been looking for a ‘smoking gun’ to link a short gamma-ray burst with a neutron star collision. The radioactive glow from GRB 130603B may be that smoking gun,” explains Wen-fai Fong, a graduate student at the CfA and a co-author of the paper describing the observations.

The team calculates that about one-hundredth of a solar mass of material was ejected by the gamma-ray burst, some of which was gold. By combining the estimated gold produced by a single short GRB with the number of such explosions that have occurred over the age of the universe, we can conclude all the gold in the cosmos might have originated from gamma-ray bursts.

“To paraphrase Carl Sagan, we are all star stuff, and our jewelry is colliding-star stuff,” says Berger.

The team’s results have been submitted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and are available online. Berger’s co-authors are Wen-fai Fong and Ryan Chornock, both of the CfA.

Posted: 23 July 2013

-

Categories:

Astrophysical Observatory , Feature Stories , Science and Nature