Eleven collection objects giving us the creeps this Halloween

As Halloween approaches, we asked museum staff to share objects from the collections that evoke the holiday’s spooky spirit. The result? Some diverse objects that creep us out just a little, which is part of why we love them. (This post was originally published by the American History Museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?)

First up, we have a picture from our photography collection of “Miss Estelle the Long Haired Queen,” whose expression we find a tad creepy. While we’re not sure of the specifics regarding Miss Estelle, Project Assistant Ryan Lintelman explains that our photography collections include a number of similar photographs depicting circus and “side show” performers. These types of traveling shows were popular around the turn of the century; visitors would pay to take a peek behind a curtain or to enter a stall or tent where people with unusual features were exhibited (long hair, extreme strength, and missing limbs were common). Cards like this one may have been sold as souvenirs.

This photograph is called a cabinet card, which is the name of a specific size of paper photographic print mounted on cardboard. This card was likely made in the last quarter of the 19th century, probably close to 1890. The photographer’s name is illegible but is printed on the back of the card along with “Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.”

While we’re on the subject of hair, how about this decorative wreath made out of it? Greg Kenyon, a Collections on the Web curator in the Division of Work and Industry, tells us that during the mid-19th century, hair-work became a viable commercial venue and a popular parlor task for women, similar to knitting or crocheting. The hair-work served as an expression of the Victorian ideals of sentimentality. It seems odd (and a little creepy) to us now, but people would exchange hair with friends, keep it as mementos of deceased loved ones, or display it as a souvenir.

This wreath, made by Mrs. Jemima Cattell Little in Newton, Iowa, around 1865, would have been hung on a wall as decoration. The hair was wrapped, woven, or braided around gauged wire to help keep its shape.

We found the hair wreath while on a recent foray into the Work and Industry collections, which is also where we found this next object. With its long beak, single eye, and oddly monkish hair, this cane handle, which could also be used as a pipe, has become a quick favorite in the New Media Department (we’re calling it “vulture pelican thing”—lovingly, of course). We don’t know much about the object’s past—who made it, when they made it, or where it might have come from are all mysteries—which, if you ask us, makes the handle even creepier.

Although we don’t know many specifics about this object, we do know that the museum collected it as an example of material manufacturing; the cane handle is made from elk horn. There are threads at the bottom that would allow the handle to be screwed onto a cane. When removed, another hole appeared, and the handle could become a pipe.

Fast-forward into the 20th century and we can find the adorably spooky dog Scraps, a stop-action puppet created by Graham G. Maiden for the 2005 Tim Burton film Corpse Bride.

This stop-action puppet, one of 14 from Corpse Bride in the museum’s collection, reflects the macabre atmosphere created in many of Burton’s films and represents a more contemporary use of stop-action puppets, which were first used by filmmaker George Pal in 1930s European film shorts.

Speaking of skeletons, here’s a rather creepy image of a skull, shared with us by Shannon Perich, associate curator in the Photographic History collection. The carte de visite depicts a skull with two children seamlessly drawn into its eyes. Shannon says, “I really love the image for the great mix of the macabre skull, the sweet children, and the clever hand that blended them together.”

This carte de visite, a type of small photograph from the 19th century printed on a thick paper card, comes from an album of religious images and copies of art. We can think of it as a momento mori, a reminder of death and the fragility of life.

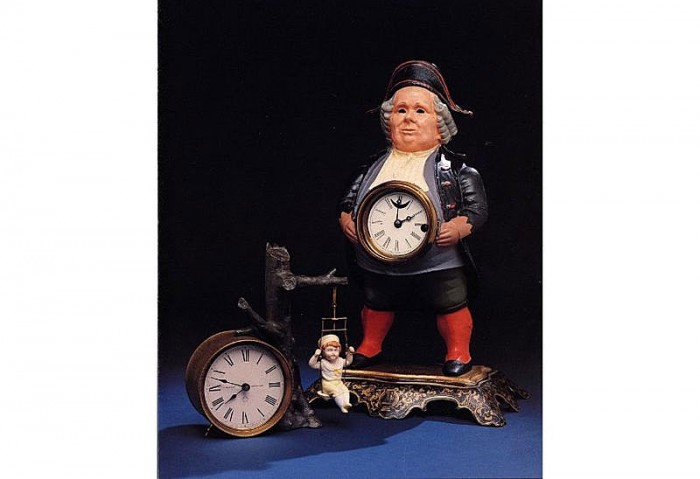

Our next object was chosen by Erin Blasco in the New Media Department. She explains why she thought it fit the bill: “During Ask a Curator Day, curator Carlene Stephens was asked about the oldest clock in the collection. She responded that a 1630s-era Scottish clock was one of our older ones and is quite complicated for the time in which it was made. Curious about our clocks, I bumped into the Winker. To me, the 1865, American-made clock seemed like a knickknack that appears innocent in daylight but becomes menacing in the moonlight, especially when mechanized. The clock protruding from the jolly belly, the lifeless eyes (designed to blink), and the oddly serious facial expression all made me want to avoid seeing this clock when it strikes midnight. Carlene assured me, ‘In person, it’s kind of sweet.’ I’m not sure I believe that.”

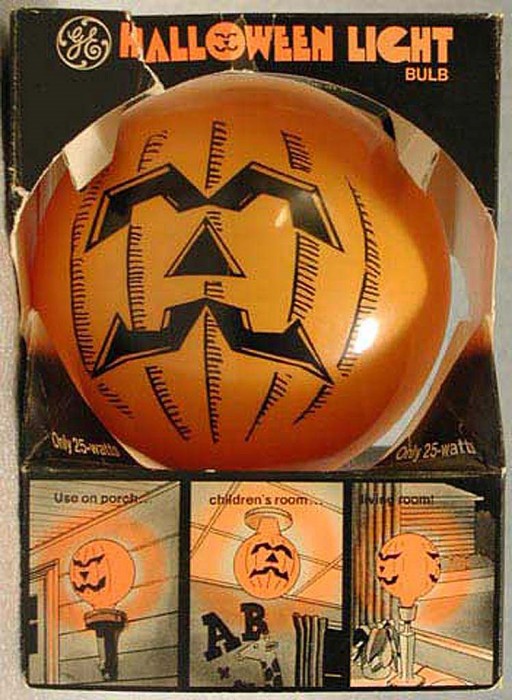

With apologies to the Winker clock, we find this Halloween light bulb a slightly less frightening option for household decoration. Hal Wallace, associate curator in the Division of Work and Industry, tells us that this light bulb was made by General Electric in the 1970s and 1980s. The jack-o’-lantern design is printed in such a way that it works whether the bulb is installed base-up or base-down.

A recent rerun of this RadioLab show brought another great creepy object to our attention. This early robot, an automaton of a friar, can imitate a walking man thanks to a wind-up mechanism. The friar’s eyes move from side to side, while one arm raises a rosary’s cross for an automated kiss and the other arm strikes the chest in the “mea culpa” gesture from the Catholic Latin Mass. Suddenly, we’re grateful that the Winker clock stays put.

This friar was probably made in Spain or southern Germany and is about 450 years old. It has been in the museum’s collections since the late 1970s.

Next up, and still in the automatons collection, we have two objects with “creep” right in their names—although they’re not supposed to be creepy. The 1871 patent model for the Natural Creeping Baby Doll and the Wonderful Creeping Baby Doll from a few decades later make, pardon our pun, a creepy-crawly pair indeed.

This patent model accompanied George Pemberton Clarke’s patent submission for a moving baby doll. The doll’s head, two arms, and two legs are made of plaster. The arms and legs are hinged to a brass clockwork body that imitates crawling by rolling along on two toothed wheels.

This doll, made c. 1900, was an improvement on Clarke’s design. Inside the doll’s body is a spring-driven brass mechanical movement that actuates the arms and legs in imitation of crawling, though the doll actually moves along on two concealed wheels.

Our last object brings us back into more modern times. You might recognize it if you like to celebrate Halloween with a horror movie marathon.

This green model of a gremlin was used in the 1990 live action horror comedy film Gremlins 2: The New Batch, directed by Joe Dante.

Do you have your Halloween costume yet? If you’re not planning on dressing up as a skeleton dog or a robotic friar (though we’d commend you if you were), try checking out this blog post for fun ideas inspired by our collections.

Leanne Elston is an intern in the New Media Department and a graduate of the University of Georgia, where she studied linguistics. She has also blogged about less creepy topics, such as Jim Henson’s puppets.

Posted: 31 October 2013

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture