Dave Van Ronk: The Mayor of MacDougal Street

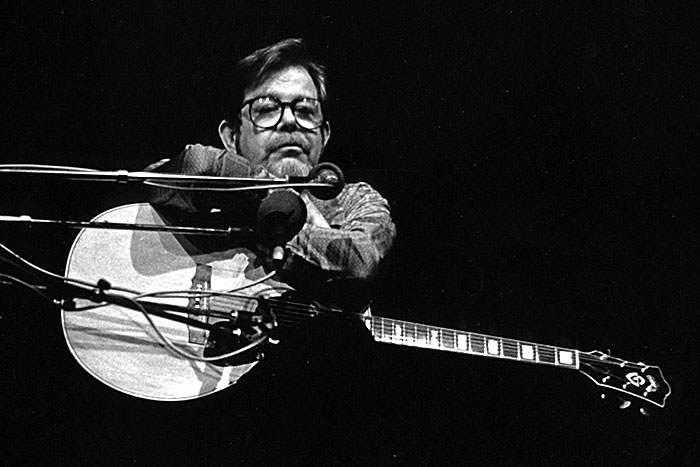

Dave Van Ronk (early in career) by Aaron Rennert and Ray Sullivan for Photo-Sound Associates, in the Southern Folklife Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

A new Coen Brothers movie and a Smithsonian Folkways box set shed new light on an artist’s storied career–thanks to archivist Jeff Place.

He was a bit like a bridge. And not just because he was big, or because he spanned an epoch stretching from Bob Dylan to Joni Mitchell to Jeff Tweedy. It’s just that if you wanted to go from mousy folkie to performer with purpose and attitude, you couldn’t go around Dave Van Ronk. You approached him, studied with him, and only then did you move on to your next destination.

Still, although he was so large and imposing, he was eventually forgotten. That’s about to change. With the release of a carefully chosen three-disc and a new movie by Joel and Ethan Coen partly inspired by his life, Van Ronk has been reconstructed, repaved, and is now ripe for rediscovery.

The man most responsible for the raspy-voiced singer’s resurrection is Jeff Place, an archivist at Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Place dug through the great man’s repertoire and came up with the bottomless, beautifully paced, three-disc set, Down in Washington Square. It begins with deep, deathless classics like “John Henry” and comes full circle with Dave covering protégé Dylan’s pessimistic tone poem “Buckets of Rain.” Place claims the upcoming Coen brothers movie, Inside Llewyn Davis, helped spark this release by the former “Mayor of MacDougal Street.”

“Somebody at Smithsonian Folkways came up to me in February or March and said, ‘There’s this new Coen brothers film coming out, based on Dave Van Ronk,'” Place recalls. “A prop person even approached me to see if they could get some old Sing Out! magazines to pepper around F. Murray Abraham‘s character’s office. Folkways then said, ‘Hey, we have all this Van Ronk stuff. We should do a collection, just in case there’s a spike of interest in Dave because of this movie. Can you do this? Can you put something together?'”

Place could and did. Rather than feeling stiflingly academic, Washington Square is a moving survey course about an alternative America in the 20th century, and the dark, dangerous folks who helped create it. Whether it’s the story of lovers “Betty and Dupree,” “Willie the Weeper,” or “Stackalee” (a homicide ballad done in various versions by Ma Rainey, Lloyd Price, and Nick Cave), Van Ronk was completely conversant with the tales of all the “little people” who created an America most of his audience knew of but rarely saw.

“What’s great about the collection,” says Place, “is that I talked to Andrea Vuocolo, Dave’s widow, who told me just before he died, Dave did all these recordings of things, some of them songs he’d already done, with new arrangements. We also had songs we recorded at a ’97 concert. At first we thought this was going to be two CDs, but we had much more stuff than we thought.”

It’s not surprising to Vuocolo that her late husband was writing new songs and tinkering with ideas in the very hospital bed where he was dying. Which makes one wonder if Van Ronk, legendary but not famous, was content with his place in the musical pantheon.

“There are several answers to that,” says Vuocolo. “He was in a comfortable place in a certain way. He was happy with what he’d done. When he was in the hospital, every day I’d walk in with a sack of mail for him. His fans were fabulous. The outpouring of support was unbelievable. That made Dave know it hadn’t all been in vain. But as far as being done, he wasn’t. He had five or six different projects he was working on in the hospital, none of which got finished. Except, thanks to Elijah Wald (co-author of The Mayor of MacDougal Street, which inspired the Coens), Dave’s memoir got out. But he was still writing songs and working on album ideas right to the end. I brought a tape recorder to the hospital and he was telling stories about the early part of his life. Artistically, he was at the top of his form. His arrangements of old songs really did evolve.”

Considering the protagonist is a selfish prick, was this, indeed, Dave?

Vuocolo chuckles mordantly.

“It’s a beautiful movie,” she says. “It’s subtle, multi-layered, and touches on so many issues. But Llewyn Davis is not Dave, and I hope people don’t think he is. Despite a sometimes gruff exterior, he had a pretty sunny disposition. He loved learning and teaching. He wasn’t a ‘trade secrets’ kind of guy. Dave’s attitude was simple, generous, and different from the movie’s protagonist. He felt, ‘If good work gets out there? That benefits all of us.'”

‘Down in Washington Square’ (Smithsonian Folkways) is available now. Visit folkways.si.edu for more information.

This article by Peter Gerstenzang was originally published by the Village Voice.

Posted: 7 November 2013

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture