We mustache you a question: Who has your favorite historic facial hair?

November is all about facial hair here at the Smithsonian, so we’re highlighting a few hairy collection objects to celebrate historic beards, mustaches and the occasional sideburn. (This post was originally published by the American History Museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?)

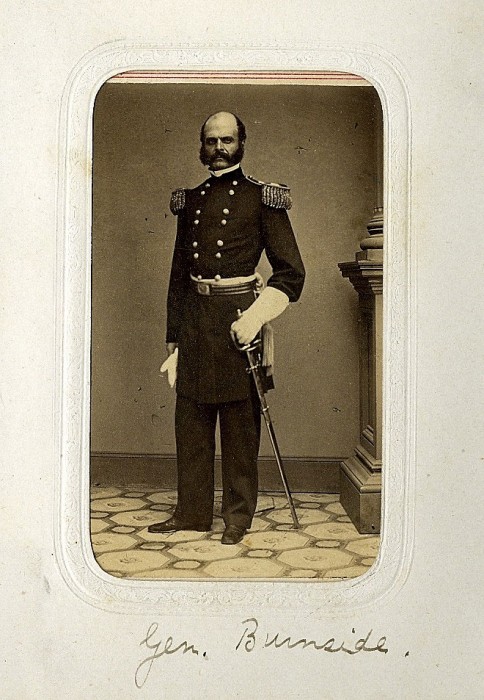

Project Assistant Ryan Lintelman selected the perfect photograph to start off a post about facial hair. He tells us about the man behind the sideburn: Ambrose Burnside was a United States Army general who rose through the ranks to succeed George McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1862. After his disastrous failure at the Battle of Fredericksburg and a personal campaign waged against him by subordinate generals (the flames no doubt fanned by jealousy of his awesome whiskers), he was removed from command but had a successful post-war career as a businessman and politician.

Perhaps Burnside’s most lasting legacy was the genesis of the term sideburn, the fashionable facial hair style that took its title from his scrambled surname.

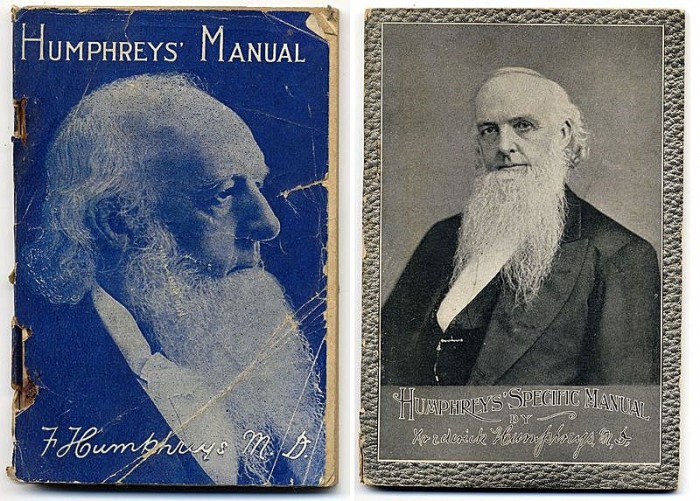

The National Museum of American History’s robust patent medicine collection includes many patent medicines that feature bearded men on their packaging (“patent medicine” refers to medicine sold “over-the-counter” without a doctor’s prescription). Katherine Ott, curator in the Division of Medicine and Science, shared these two images of Frederick Humphreys, a prominent 19th-century physician who practiced homeopathy, which often borrowed patent medicine advertising techniques.

Humphreys’ distinctive beard, in the popular style of the era, was good advertising copy for the products his company produced. Here, we see his image on two of his publications, both homeopathy manuals.

On a recent trip into the Work and Industry collections, we found a couple of creepy objects that we featured in our Halloween blog post. We also discovered this umbrella handle, which, thankfully, is not creepy but showcases a rather impressively mustachioed man carved from horn.

This umbrella handle, 4 ½ inches long and carved from horn, was collected in 1875 as an example of material manufacturing. A 19th century log book listing other items in the collection describes the handle as “a grotesque human head with hat, glass eyes,” though we think “grotesque” is a little harsh.

The National Museum of American History is home to more than a few odd objects (have you seen the display case of presidents’ hair?), and this object combines the best of both beards and America. When he heard that the blog team was looking for historic beards, associate curator Steve Velasquez from the Division of Home and Community Life came running with a photocopy of a museum record he’d had displayed on his office bulletin board documenting the accession of an actual beard into the museum’s collection. It’s the beard that Californian Gary Sandburg grew and dyed red, white, and blue to celebrate the American bicentennial on July 4, 1976.

Sandburg donated his beard to the Smithsonian for safe-keeping. The museum thanked him with the following well-chosen words: “Dear Mr. Sandburg: We were delighted to receive your amazing bicentennial beard. It is certainly a unique offering which shows great imagination as well as national pride. Although we do not know where or when we will be able to exhibit it, we are very happy to add your beard to our collections.” And we’re happy to include it in this blog.

Northwoods Hairstyling of Downey, California, dyed this beard for Gary Sandburg, who later sent it to the Smithsonian. The American bicentennial commemorated the 200th anniversary of the convening of the Second Congress in the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, July 4, 1776, and the signing of the Declaration of Independence, which called for separation from Great Britain and the creation of the United States of America.

Dwight Blocker Bowers, curator in the Division of Culture and the Arts, was eager to share these next objects. These false mustaches, which he says he thinks look like caterpillars, are humbly pinned to a few pieces of cardboard and stored in a simple box. Dwight explains that actor James Whitmore wore the mustaches in his performance as Teddy Roosevelt in the 1978 Broadway production of Bully: An Adventure with Teddy Roosevelt, a one-man stage drama by playwright Jerome Alden.

The various mustaches, ranging in hair color from auburn to gray, allowed Whitmore to visibly “age” over the course of the play.

Robyn Einhorn, a specialist in the National Numismatic Collection, volunteered our next objects. During the latter half of the 19th century, the federal government circulated bills called fractional currency in order to offset the lack of metal and coinage brought on by the Civil War. The currency, which featured a portrait of William Meredith (Secretary of the Treasury from 1849-1850), became a blank canvas for satirical artists, who made a variety of humorous additions to the bills. We selected a few of our favorite examples featuring some fun facial hair.

It’s doubtful that the artists of these artistically manipulated portraits were politically motivated or aimed to ridicule Meredith. It’s more likely that they were illustrating their lack of trust in both the currency’s value and their government’s ability to back that value.

Speaking of currency, Robyn showed us these next objects as well. Nicknamed “hobo coins,” these nickels come from the 1930s during the years of the Great Depression. The story goes that unemployed workers in train box cars would use a hammer and nail to alter the image of the American Indian on the obverse of James Earle Fraser’s buffalo nickel. As with the fractional currency, adding facial hair seemed to be the new design of choice, and these nickels display a fun range of beards. When the nickel modifiers reached their next town, they would sell or trade their carved nickels for necessities.

In reality, the practice of re-carving the American Indian’s image probably began years earlier, with the manufacture of the buffalo nickels in 1913. Whenever the nickels got their new looks, and whoever the artists were, today these coins are highly valued and sought by collectors.

We don’t know who added the beards to the American Indian on these coins, but their humorous carvings certainly make a great addition to our collection of historic facial hair. Be honest: who’s eyeing the bust of Thomas Jefferson on the nickels in their wallets right now and thinking he needs a beard?

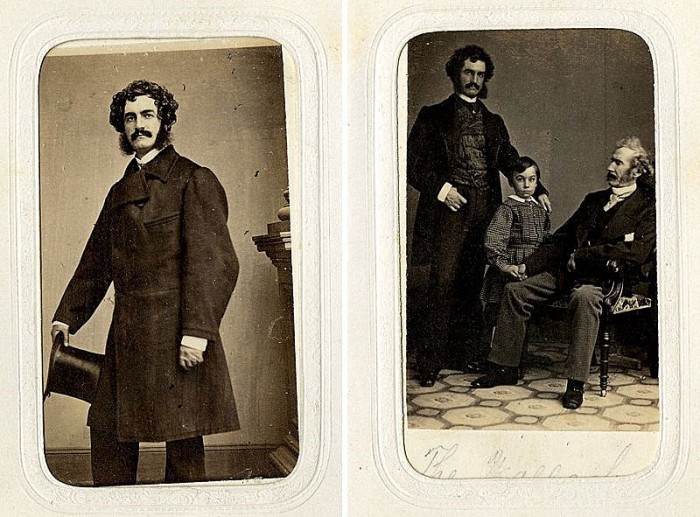

Ryan Lintelman, who picked out Ambrose Burnside for us, also found these photographs of English actor John Lester Wallack among the museum’s extensive Civil War photography collections. Wallack found great fame in American theaters as the lead in comedies and romances from the 1840s-1870s. “Who could resist those seductive sideburns?” Ryan jokes.

These photographs are labeled “Lester Wallack” and “three generations of the Wallack family.” The one on the right suggests that great facial hair may have run in the family.

“Don’t Smart, BE Smart! Get That Diexin Feeling.” If you’re not a fan of facial hair, this next object might be for you. “Whisker-wilting Diexin” is the patented special ingredient in Krank’s Brushless Shave Kreem, which Diane Wendt, associate curator in the Division of Medicine and Science, shares with us. Krank’s Kreem was made by the Royal Consolidated Chemical Company and first appeared in 1944, lasting well into the 1960s.

The box’s instructions on how to use Krank’s Kreem are easy enough to follow: “1. Wet your face! 2. Spread on Krank’s! 3. Shave! No Brush…No Soap!” Anybody going to give it a try?

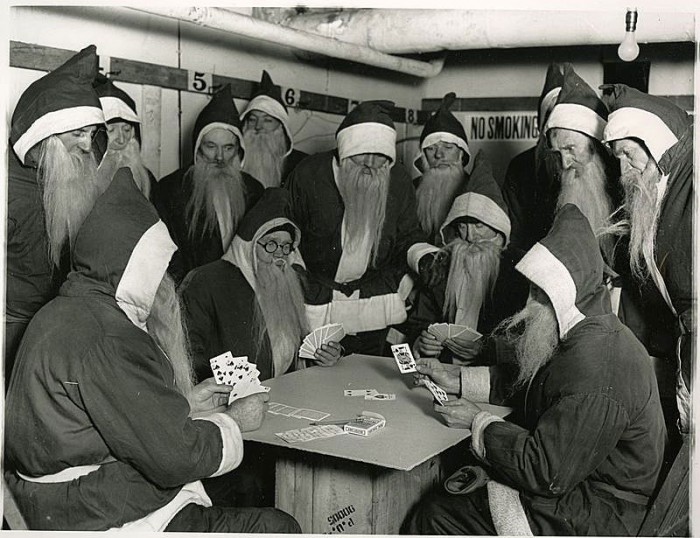

Christmas is just around the corner, and that means Santa beards aplenty (to wear on your now clean-shaven face, thanks to Krank’s). Shannon Perich, associate curator of the Photographic History Collection here at the museum, selected this Underwood & Underwood photograph during our recent Ask a Curator Day as an object that makes her laugh. We immediately bookmarked it as a fun example of beards—although these Santas don’t look all that cheerful.

This 1920s photograph was taken by news photo distribution company Underwood & Underwood during Christmastime in Chicago.

Can’t get enough facial hair? Check out the Smithsonian ‘Staches Pinterest board featuring plenty more bearded and mustachioed men.

Leanne Elston is an intern in the New Media Department. She has previously blogged about Jim Henson puppets, the museum’s World War II billboard currently on display, and creepy Halloween objects from the collections.

_________________________________

Editor’s note: Oh, no you don’t! You don’t think we’re going to let a post about facial hair pass without posting this, do you?

National Museum of Natural History’s physical anthropologists Lucille St. Hoyme, J. Lawrence Angel and T. Dale Stewart hold a 17.5-foot-long beard found in a North Dakota attic. We know no more about this artifact, nor do we want to. From the Torch, September 1967.

You’re welcome.

Posted: 5 November 2013

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture