Show me the money!

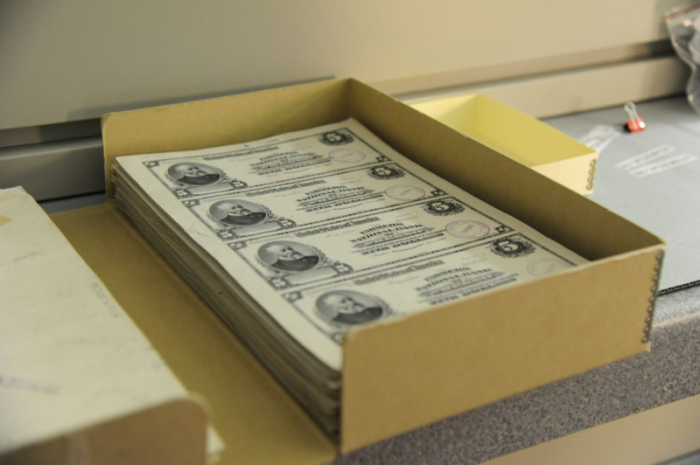

Have you ever seen a box full of money—well, not exactly, money, but certified plate proofs? What about stacks of boxes of money? Stacks on stacks? Unless you’re a regular in the National Numismatic Collection vault, chances are you haven’t seen anything like it. Over the course of one week, these boxes were opened up, their contents digitized, and now their content is going online for all to see—and help transcribe. Peter Olson interviewed some of the staff responsible for opening this trove to the masses.

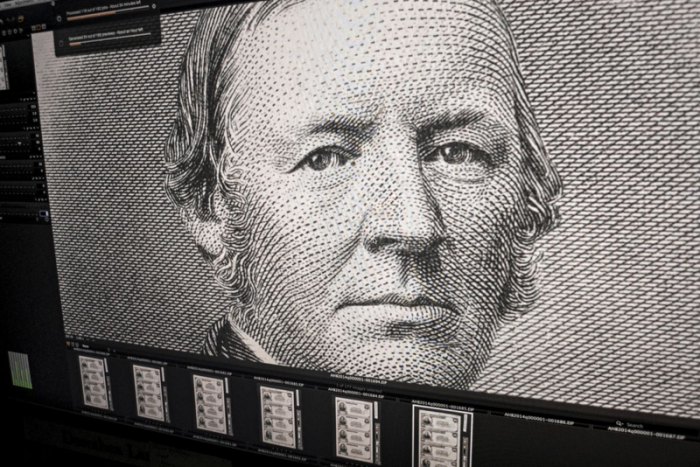

Some of the 3,069 proof sheets digitized in just a week in the National Numismatic Collection. Certified proofs allowed the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to examine every intaglio printing plate before it was placed in production, signing off that everything was correct before printing large quantities. These proof sheets make up part of a rarely exhibited collection of proofs of currency, bonds, revenue stamps, checks, and even food coupons.

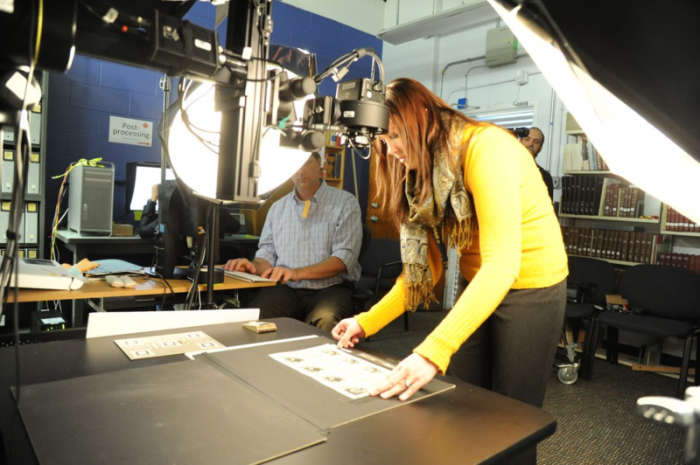

All last week, staff from across the Smithsonian stopped by the National Numismatic Collection area at the American History Museum to see a unique process called “rapid capture digitization” in action. The Numismatic Collection team is working in partnership with the Smithsonian’s Office of the Chief Information Officer’s Digitization Program Office and the National Currency Foundation. It allows collections specialists to gather visual, textual, and other data from museum objects quickly and make all this available digitally at a very high quality level.

That may not sound impressive until you compare the speed of rapid capture to traditional methods, in which a single scan might take 20 minutes. It would take months to complete what was accomplished in just a week.

While the demonstration room was full of computers and cameras, the process isn’t just a technical one.

“It’s an education process,” says Jennifer Jones, chair and curator of the Division of Armed Forces History, which includes the National Numismatic Collection. “It’s to show what’s possible and to get these [proofs] to the public.” But these objects aren’t just available for looking—in this project, the public has a very special chance to interact with these proofs through the Smithsonian Transcription Center, where anyone can volunteer five minutes or five hours to transcribe text and information about the objects to create and enhance their online records.

This is a big step for a Smithsonian museum. “We don’t often let incomplete data out, but we are for transcription,” continues Jones. Giving the public a chance to help complete these records opens up a whole new world of volunteer opportunities for museum lovers.

The transcription volunteers are an integral part of this process.

“There are about 2,800 regular volunteers,” says Dr. Meghan Ferriter, project coordinator for the Smithsonian Transcription Center. These volunteers are capable of transcribing and reviewing 60-700 pages per week, with a record volume day of 215 pages transcribed. Once transcribed, collections information becomes far more searchable and useful to researchers and the general public.

“Our volunteers believe in helping the Smithsonian.” Feritter continues, “We are continuing to evaluate quality, but we are positive and comfortable that our volunteers are making trustworthy transcriptions. This quality is absolutely crucial and we are learning more everyday by collaborating with our volunteers. Transcriptions make collections more accessible to both researchers and the public. With these projects, we are increasing the detail of Smithsonian collections by actually creating collections records—all through special access to these rarely exhibited proof sheets via the Transcription Center.”

This entire process is designed for rapid turnaround. How rapid?

“We’re seeing a turnaround of about 36 hours. From the vault shelf to the public, that’s the approach.” says Ken Rahaim, still image program officer with Smithsonian Digitization Program Office.

“As soon as it’s live, volunteers jump into the project.” says Dr. Ferriter. The transcribers even tweet with each other to swap tips and share successes.

The pace truly is impressive given the quality of the work. These images are captured at 80 megapixels and create images with resolution of 690 pixels per inch. This allows intricate designs of only two micron thickness to be captured and analyzed or simply marveled at by a numismatist. When given the chance to examine an image, I could zoom in a seemingly infinite amount and still have a crisp image to study.

The rapid capture trial is a marked change from the way digitization of currency has happened in the past. Andrew Shiva, founder of the National Currency Foundation and regular Smithsonian volunteer says, “This project started with just a flat scanner doing a page or note at a time. This doesn’t work well with large sheets. It could take 15-20 minutes per sheet and there are 300,000 sheets! It’s phenomenal to do in a day what would have been a couple of weeks in standard resolution.”

In the end, 3,069 proof sheets were captured. That’s “20 boxes and represents sheets from seven different states,” says Hillery York, a collections manager in the Numismatic Collection.

Perhaps even more impressive than the number and speed of captures was the sense of inspiration among Smithsonian staff who visited the demonstration—many of the over 140 staff who visited walked back to their offices pondering how they’d use rapid capture digitization in their own work.

So what’s next for the Smithsonian Digitization Program Office? “Our next Rapid Capture Pilot Project will be at the Freer-Sackler capturing ceramic pottery followed by Pilot Projects at the National Museum of Natural History and the National Air and Space Museum,” says Ken Rahaim.

Even Smithsonian Secretary Dr. Wayne Clough and Dr. Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture, stopped by to see the process—and got put to work. (Photo by Günter Waibel)

Are you interested in historical currency? How about botany or historical writings? Help the Smithsonian out by volunteering with the Smithsonian Transcription Center. More photos of this pilot project are available on Flickr. This post by Peter Olson, an intern in the New Media department of the American History Musuem, originally appeared on the blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 18 March 2014

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Art and Design , Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Science and Nature