Smoke gets in your eyes

It has been 50 years since the U.S. Surgeon General’s first report detailing the health hazards of smoking. Jeffrey K. Stine, the American History Museum’s curator for environmental history, explores the tobacco industry’s greater reliance on advertising during the mid-20th century, a topic well documented across the museum’s collections.

Just days before this museum opened its doors to the public as the National Museum of History and Technology in January 1964, newspapers across the country ran stories under headlines such as: “Cigarettes Health Hazard, Panel Says” (Buffalo Evening News), “Cigarettes ‘Health Hazard'” (Lowell Sun).

Sensing the need to counter the growing questions being raised about the risks of smoking, tobacco companies increased their reliance on advertising during the mid-20th century. The peddling of tobacco products during this period often involved deliberately masking the hazards of smoking—indeed, the ads frequently claimed or implied that smoking was healthful.

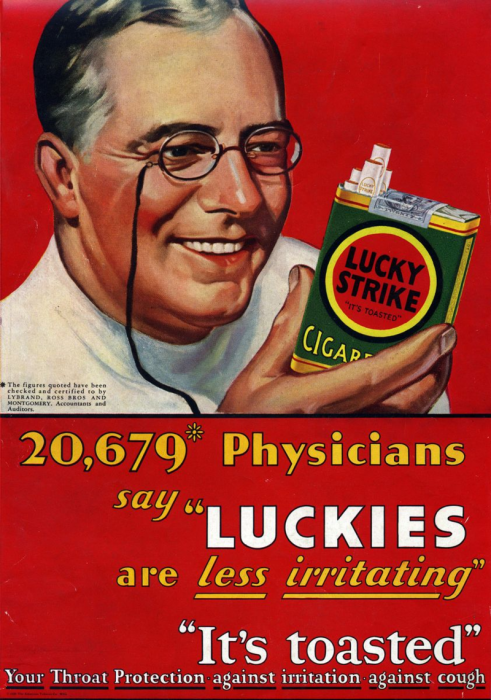

This 1930 ad for American Tobacco Company’s Lucky Strike cigarettes used an image of a physician to make health claims like “Luckies are less irritating” and “Your Throat Protection—against irritation—against cough.”

Tobacco marketers featured healthy, vigorous, fun-loving people in their ads. Often these were celebrity figures from sports and entertainment fields, other times they featured actors portraying physicians, dentists, or scientists. Some ads tapped into concerns about weight gain; some portrayed the middle-class comforts of home, holiday, recreation, or family pets.

For historians wanting to study the role of advertising, popular culture, and image-making on public attitudes and the social acceptability of smoking, this museum holds unparalleled research collections. Among the most colorful and provocative are the over 10,000 tobacco advertisements in the museum’s Archives Center, recently donated to the Smithsonian by Dr. Robert K. Jackler and his wife, the artist Laurie M. Jackler.

Motivated by the death of his mother from cancer, Dr. Jackler sought to document the concerted effort to popularize smoking, and the conscious attempt to obfuscate smoking’s known health hazards. Working with his wife and Stanford University historian of science Robert N. Proctor, Jackler not only preserved the full range of tobacco ads but compiled a database that allows users to search on particular themes, including ads featuring babies and young people.

As Chair of the Department of Head and Neck Surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine, Dr. Jackler collected a 1930 ad for the American Tobacco Company’s Lucky Strike cigarettes (shown at the top of this post) as the epitome of the era’s “manipulative quackery.”

Advertisements often sought to reassure the public by showing health professionals making false claims, such as “Luckies are less irritating” and “Your Throat Protection—against irritation—against cough.” Advertisers incorporated a wide range of trusted authority figures to market products for tobacco companies. A 1949 ad produced for the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation shouted that “Viceroys filter the smoke!” and used an image of a solemn dentist recommending the brand.

Advertisers incorporated a wide range of trusted authority figures, including health professionals, to market products for tobacco companies, such as this 1949 ad produced for the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation.

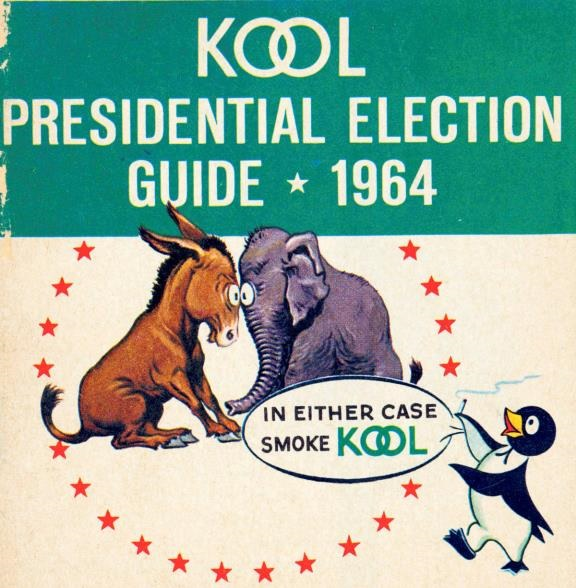

In 1936, the advertising agency for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company began using the KOOL penguin icon to pitch the menthol-flavored cigarettes during presidential elections. The penguin was illustrated as a calming arbitrator between mascots of the two competing political parties, and thereby implied that smoking KOOLs was a calming choice for supporters of either party. A 40-page 1964 KOOL Presidential Election Guide included information on the election process and outlined the platforms of incumbent Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson and his Republican challenger, Barry Goldwater.

This 1964 KOOL Presidential Election Guide produced by an advertising agency for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company offered information on the election process and the two candidates: incumbent Democratic president, Lyndon B. Johnson, and the Republican contender, Barry Goldwater.

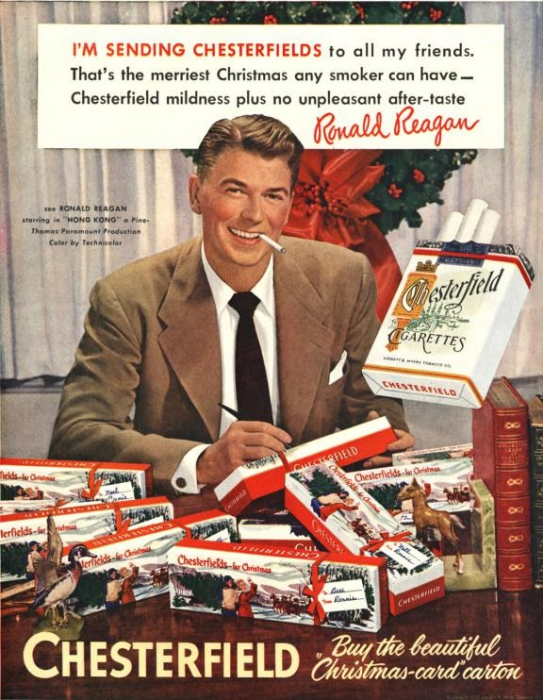

Advertisers also made extensive use of celebrities. An ad that appeared around 1950 featured the actor Ronald Reagan, who assured readers that he was “sending Chesterfields to all my friends. That’s the merriest Christmas any smoker can have—Chesterfield mildness plus no unpleasant after-taste.”

This ad, which appeared around 1950, featured the popular actor Ronald Reagan—and included promotion for his latest film, “Hong Kong.”

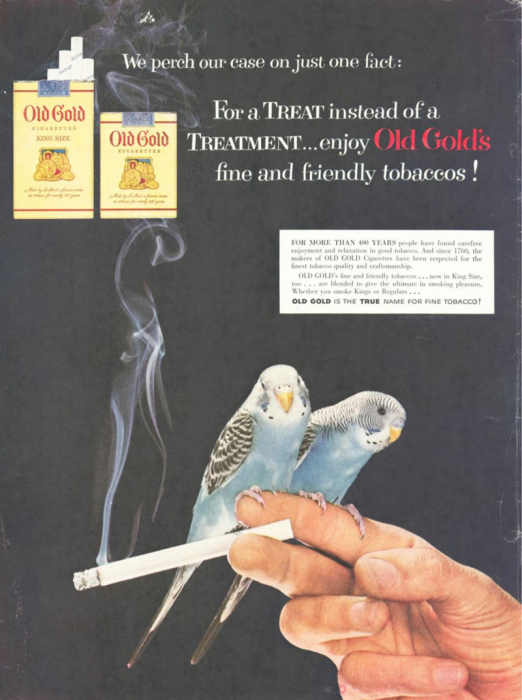

Tobacco marketers sought to engage young customers by exploiting a connection to animals, both real and imaginary. Old Gold cigarettes launched a post-World War II advertising campaign revolving around beloved family pets, such as in a 1954 ad showcasing a pair of finger-trained budgerigars.

This 1954 advertisement for Old Gold cigarettes exploited the post-World War II popularity of parakeets

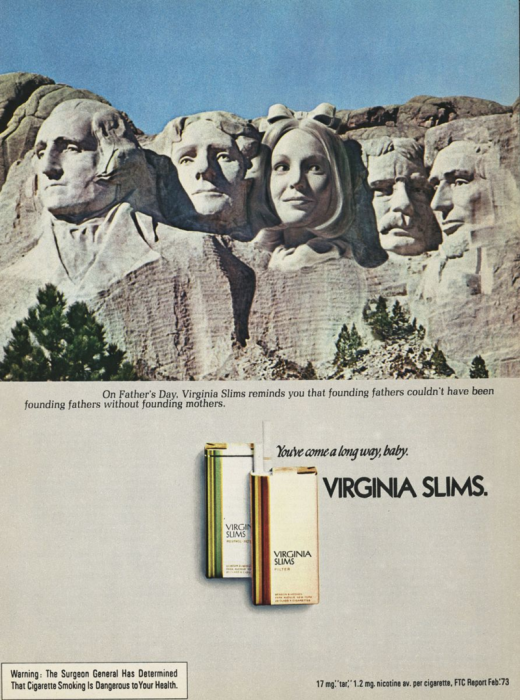

American corporations enthusiastically tagged products to the women’s movement. In 1968, the Philip Morris Company introduced its Virginia Slims brand of cigarettes. The highly successful marketing campaign—with the memorable tagline, “You’ve come a long way, baby”—targeted young, professional women by co-opting the phrases, imagery, and values of the political movement and eventually sponsoring major tennis tournaments for women. One 1973 ad remarked that: “On Father’s Day, Virginia Slims reminds you that founding fathers couldn’t have been founding fathers without founding mothers.”

The Philip Morris Company introduced the Virginia Slims brand of cigarettes in 1968 with the memorable tagline, “You’ve come a long way, baby.”

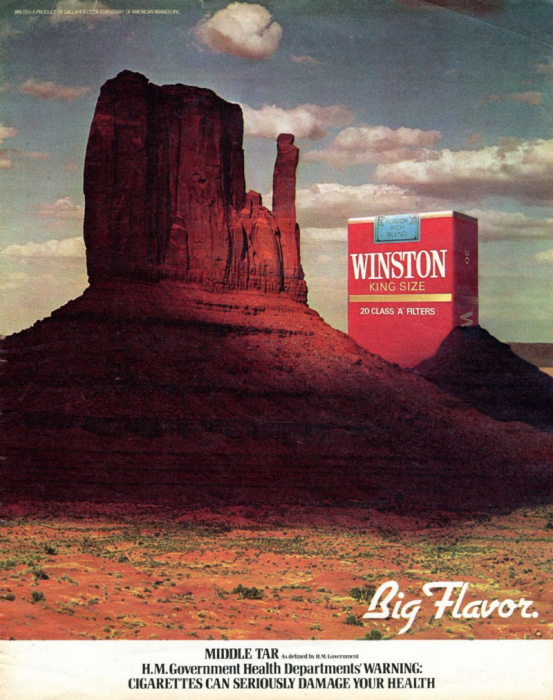

Even America’s natural landscapes were not immune to exploitation, especially when advertisers hoped that the connection would imply that a product was both liberating and healthy. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company—whose slogan “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should” raised the eyebrows of grammarians—used a quintessential Western landmark in Monument Valley to market Winstons abroad as an unquestionable American brand.

R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company used a quintessential American landscape to market its Winston cigarettes abroad

This post originally appeared on the American History Museum blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 24 March 2014

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture