The Great Apes reveal their secrets

The largest fully preserved great ape collection in the world is about to make its online debut. Scientists from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History have been working during the last few weeks to CT scan all 38 specimens in the museum’s “wet” great ape collection, including chimpanzees, orangutans and even a full-grown western lowland gorilla. Once completed, the thousands of high-resolution scans of the animal’s insides will be made publicly available on the Internet, giving scientists from around the world access to a once largely inaccessible collection.

Our collection is more than just bones

Beyond just the bones contained in the Natural History Museum’s dry collections, with which the public is most familiar, the museum’s “fluid” collection preserves the entire animal in an alcohol solution.

“Our fluid specimens are an invaluable resource as the entire animal is preserved intact,” says Darrin Lunde, Mammals Collection Manager for the museum. “We have the muscles, we have the internal organs, we have blood vessels – nothing is lost. These specimens are invaluable for researchers wishing to study tissues and internal organs that the dry collections cannot provide.”

Scientists from around the world seeking to answer questions in biomedical, environmental and evolutionary fields have vied for access to this fluid collection for years but have been restricted by the difficulties in handling the preserved great apes.

“Wet specimens are difficult to work with,” Lunde says. “These new high-definition scans will enable researchers to non-invasively study tissues, organs and bone structure from our specimens from the comfort of their computer screens anywhere in the world.”

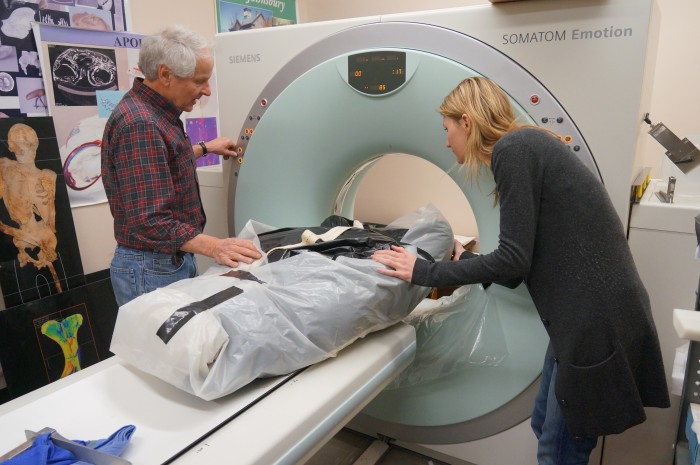

Bruno Frohlich and Sabrina Sholts retrieve a specimen from its storage container at the Smithsonian Museum Support Center in Suitland, Md. (Photo by Micaela Jemison)

Speed, care and alcohol fumes

While the final product will mean endless possibilities for research, getting the apes scanned is a mammoth undertaking. Preserved in alcohol tanks the size of small compact cars, fishing out the apes is no small feat. Transporting the animals also must be done with the utmost speed and care due to their fragile condition.

Well aware of the medical insights the great apes could provide, Smithsonian Biological Anthropologist Bruno Frohlich, along with other museum staff, has spent weeks scanning the specimens in often smelly and certainly challenging conditions. A round-the-clock cycle “ape shuttle” has transported the great apes from their tanks at the Smithsonian Museum Support Center in Suitland, Md. to the Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C. for scanning.

Placing the great apes in the CT scanner comes with its own risks, not only to the specimens but to the scientists themselves.

“To ensure the specimens remain in pristine condition, they must be kept moist in their alcohol solution” Frohlich says. “The alcohol fumes, however, are highly flammable and an explosive hazard should any electrical sparks from the equipment come in contact with them. To protect both us, the apes and the scanner, we place the apes in specialized bags that keep them wet and the fumes inside.”

An orangutan, part of the the great ape wet collection maintained by the National Museum of Natural History’s Division of Mammals. (Photo by Micaela Jemison)

Will the king of jungle fit through the scanner?

The scanning of the great ape collection is nearly complete but the final hurdle is proving to be quite the challenge. All that remains is to scan the centerpiece of the collection, a full-grown male western lowland gorilla known as “Hercules.” Weighing in at roughly 400 pounds, his gigantic size may prove to be too much for the museum’s CT scanner to handle.

If scanning the gorilla can be achieved, it and the other 37 specimens will provide research insights for scientists all over the world. “To my knowledge this is the first time a large collection of great ape anatomical specimens is being made available online,” Lunde says. “Having these scans not only means we can try to answer many of the research questions we have now, but also the many more to come in the future.”

Bruno Frohlich and Sabrina Sholts guide a great ape specimen, wrapped in plastic for protection, through a CT scanner at the National Museum of Natural History. (Photo by Micaela Jemison)

Micaela Jemison is a bat ecologist and science communicator. Originally from Australia, Micaela moved to the USA in 2013. She is currently a Science Writer intern for Smithsonian Science and a research student in the Department of Mammals at the National Museum of Natural History. She is also the Communications Officer for the Australasian Bat Society and is working with Bat Conservation International on conservation projects in the Australasian region.

Posted: 14 March 2014

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature