Lions and tigers and bears–no lie!

Cheetah Miti and her cubs, five female and one male, born last November at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, Va. (Photo by Adrienne Crosier)

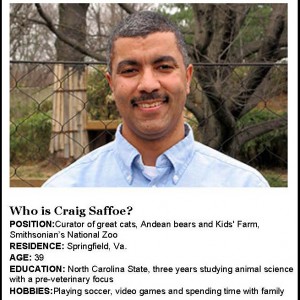

In a maze of indoor cages located beneath the lion and tiger yards at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, Craig Saffoe paused while the ungodly roar of a lion named Luke reverberated around the building, drowning out conversation and creating vibrations underfoot.

It didn’t faze Saffoe, whose job is managing the zoo’s lions and tigers and bears—no lie.

But the job involves more than just keeping animals healthy and on view. Saffoe also helps educate the public about conserving these animals, many of them endangered, and supports worldwide efforts to sustain them.

“It’s a dream job. Most folks who work here would say the same thing,” said Saffoe, curator of the zoo’s great cats, Andean bears and the Kids’ Farm.

When working with a collection of live animals, there’s no such thing as a routine day, Saffoe pointed out. One day, an animal might act as though it’s interested in breeding. On another day, an animal might be imported to live at the zoo or one will be shipped out.

When working with a collection of live animals, there’s no such thing as a routine day, Saffoe pointed out. One day, an animal might act as though it’s interested in breeding. On another day, an animal might be imported to live at the zoo or one will be shipped out.

“I really get pulled,” he said. “It keeps it exciting, keeps it from getting stagnant. I have to make snap decisions.”

Recently, Saffoe helped lower two of the zoo’s four newest African lion cubs into a moat in the lion’s yard, one by one, during their first time outside. Playful cubs who roughhouse and swat one another could wind up in the water, he said, and it’s important to make sure they know how to get out. The cubs passed the test swimmingly.

Saffoe also helps the zoo as it works to save threatened species worldwide. With fewer than 400 Sumatran tigers left in the wild, for example, Saffoe represents the National Zoo in a cooperative arrangement with an American zoo association and other zoos’ representatives, to share input as they create survival plans for maintaining the population and health of the tigers and other rare species.

“If we do that well, we maintain a genetic safety net of animals,” he said. The zoo was rewarded in August when a tiger gave birth to two cubs.

Juan Rodriguez, a keeper for the Giant Pandas, credits Saffoe’s management skills for the success of the large cat program.

“He has the foresight to know where to go for managing the collection,” Rodriquez said. “Sumatran tigers are critically endangered and he brought a pair here. As you can see, that worked out.”

Preventing a species’ extinction takes help from governments, indigenous people and others, according to Saffoe. One of the ways he played a part was by traveling to Namibia to teach a college conservation ecology class on captive husbandry techniques to assist the Cheetah Conservation Fund, which works on sustaining the local wildlife.

“The part of my job I absolutely love is contributing to conservation in ways people don’t think of,” Saffoe said.

Visitors often glamorize the jobs of zoo staff. For example, Saffoe frequently is asked if staff can play with the animals. Sometimes, he jokingly answers, “Yes, but only once.”

The public is generally unaware of the gritty parts of the job, such as dealing with a broken pipe in an animal’s enclosure or with an animal that has swallowed something it shouldn’t have. Other challenges include having to euthanize an animal, separate a mother from her cubs or face the danger involved in getting an animal into a crate for a medical exam if it can’t be trained to walk in willingly.

“My mantra is, `If something we have to do knowingly puts a person in harm’s way, it should be me,’” Saffoe said, not one of the eight keepers who report to him.

He also noted that a wrong decision on treating an animal can lead to trauma or death. “Sometimes I have knots in my shoulders from the decisions I have to make,” he said. “They can weigh on us a lot.”

Saffoe’s office, pungent with the scent of large cats, recently contained a crate being modified to transport a fishing cat—a small, endangered species native to Southeast Asia that he said could be confused for a large gray tabby. He wanted to be sure curious onlookers wouldn’t be tempted to open it.

“We don’t want an airline attendant to think this is an animal used to handling,” he said.

The road to Saffoe’s job began in high school when he became enamored of the local “gutter cats,” as the locals called them. He managed to capture a female feral cat by tying a string to a trap and watching and waiting.

Saffoe’s love of big cats snowballed and he read everything he could on them. He gained mentors when working weekends at a veterinarian’s kennels and interning at the National Zoo. While still in college, he landed a full-time position working with the zoo’s cheetahs and he’s been there ever since.

“It was a series of meeting the right people at the right time,” he said. “It’s been amazing.”

This article was jointly prepared by the Partnership for Public Service, a group seeking to enhance the performance of the federal government, and washingtonpost.com.Go to the Fed Page of The Washington Post to read about other federal workers who are making a difference.

Posted: 12 May 2014

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Science and Nature , Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute