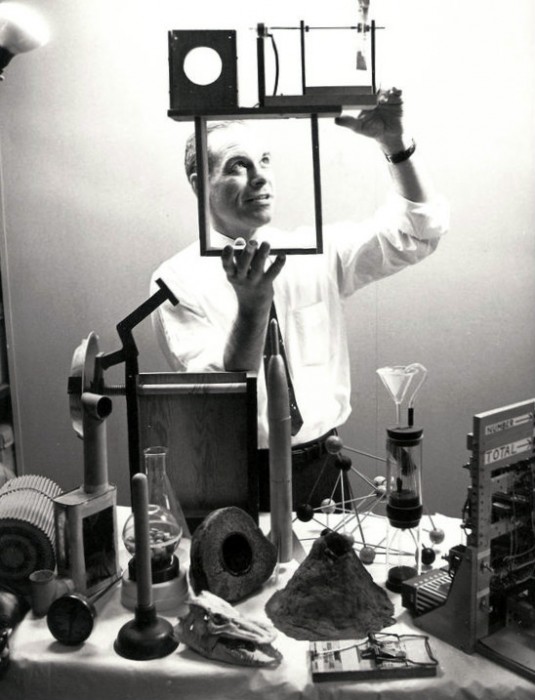

The original Mr. Wizard used science, not magic, to work everyday wonders

Authoritative, intelligent and always accompanied by a young assistant, television’s Mr. Wizard brought science to America’s kids from the 1950s through 1980s with experiments using household items like eggs, balloons and coffee cans. While many may remember him from his 1980s program on Nickelodeon, Mr. Wizard’s career spanned decades. Now an important piece of Mr. Wizard has come to the Smithsonian.

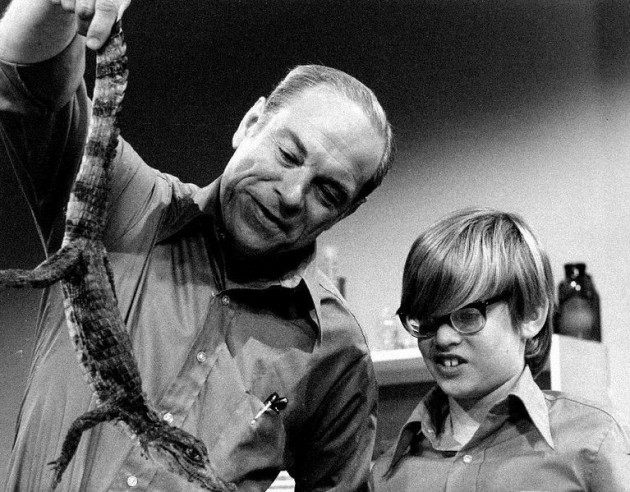

Don Herbert, with a young assistant, exhibiting an example of “Living Animal Fossils” on “Mr. Wizard” in 1971.

This month a trove of personal papers, files and other items belonging to the late Don Herbert—Mr. Wizard—was acquired by the Archives Center of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. The materials, a donation from Herbert’s daughter and son-in-law, Kristen and Tom Nikosey, will be conserved and organized by the Smithsonian’s Archives Center and are permanently available to researchers interested in Mr. Wizard and his place in American history.

“The Mr. Wizard collection reveals how Herbert planned meticulously to share science with the rest of the country through children. His shows were aimed at children to really get them interested in science, and it worked,” Smithsonian Archivist Craig Orr explains.

Donald Jeffry Herbert (1917-2007) was creator and host of “Watch Mr. Wizard” (1951-1965), “Mr. Wizard,” (1971-1972) and “Mr. Wizard’s World” (1983-1990), popular television programs for children that demonstrated and explained basic principles of science and technology.

“In the early 1950s Herbert used the relatively new medium of television to spread the word about science and capture imaginations,” Orr says. “Mr. Wizard introduced a lot of people to science in an entertaining, informative way.”

Cool and always calm, “Watch Mr. Wizard” flickered into America’s living rooms at a critical time when science was driving many aspects of people’s lives. “The atom bomb had been developed and deployed in 1945, about six years before Mr. Wizard went on the air,” Orr says. “America was in a science race with the Soviet Union. When Sputnik, the first satellite, was launched it scared the heck out of everybody in America. People worried if we were scientifically prepared to keep up with the Russians.” Herbert’s TV show helped assuage some of those fears and went on to spark many new scientific careers.

Part of Mr. Wizard’s appeal was that he never addressed a TV audience, but talked to a young boy or girl assistant whom he hosted in his studio. “This show was aimed at children but it wasn’t talking down to them, it wasn’t made all fun and giggles,” Orr says.

“As with other TV shows at the time—say Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett—Mr. Wizard had his own fan clubs,” Orr continues. “Instead of just wearing coonskin caps, kids around the country would gather and recreate experiments they had seen on TV. It was really a hands-on experience.”

Herbert’s collection at the National Museum of American History consists of material that documents his entire career as a science educator from 1951 through the mid-1980s. At its core are some six cubic feet of more than 500 files prepared for “Watch Mr. Wizard” that document the meticulous care and preparation Herbert put into each episode.

Each file—one per episode—contains Herbert’s notes for the show; the day’s script; black and white photographs taken during rehearsals to plan the experiment; diagrams on graph paper of where he and his young assistants would stand and move; and notes about technical needs, such as lighting and equipment. (The original 1-inch films and kinescopes of the show were deposited with the UCLA Film and Television Archives several years ago.)

Herbert’s files also contain his research notes on the science being demonstrated. “Herbert prided himself on his scientific acumen and consulted with academics to ensure he got it right,” Orr says.

Many of Herbert’s other educational activities are equally well-documented. There are scripts for radio science shows he produced in Chicago in 1946 and1947, before he hit it big with Mr. Wizard; storyboards and film reels of the “Progress Reports” he did for the General Electric Theater; and notebooks and files relating to the 1983-1990 revival of his show on Nickelodeon, among other materials. Herbert’s papers and personal files are important to the National Museum of American History, in part, because of his relevance to other disciplines at the museum: the Physical Sciences and Chemistry collections; the Division of Medicine and Science; and the Division of Work and Industry.

“The American History Museum was originally founded as the National Museum of History and Technology. For the first 25 years our core collections were the history of technology, and technology is basically science based, so there is a strong interest in science in this museum. We don’t just collect inventions and gadgets but also information on how those things impact the wider American culture and American society,” Orr explains.

Posted: 21 May 2014