The Marx Brothers: The “comic combustion” celebrates 100 years

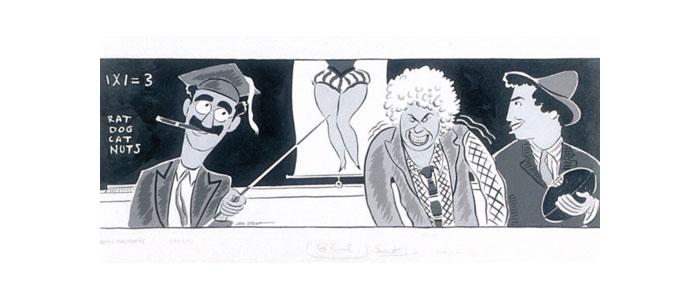

The Marx Brothers in “Horse Feathers” by Joseph Grant, 1932. National Portrait Gallery, gift of Carol Grubb and Jennifer Grant Castrup.

Melodie Sweeney, an associate curator in the Department of Art & Culture at the National Museum of American History, shares some Marx Brothers highlights in honor of the iconic trio’s 100th anniversary.

You may love the Marx Brothers’ Horsefeathers, Duck Soup, and Animal Crackers, but did you know the comedy group was once known as the Nightingales? The dynasty that changed American comedy debuted 100 years ago in 1914, a landmark year that also saw the establishment of Mother’s Day, the Model T assembly line, the opening of the Panama Canal, and the eruption of World War I.

Adolph and Minnie Marrix, Jewish immigrants from France and Germany, settled in New York City and raised five sons: Leonard, Arthur, Julius Henry, Milton, and Herbert. A musically inclined family, the brothers were encouraged into the limelight at an early age by their mother, Minnie, and during the first decade of the 20th century the Nightingales performed a musical variety act on the vaudeville circuit.

Suit with black swallow ail jacket and striped pants worn by Groucho Marx on the television program “You Bet Your Life”. Gift of Groucho Marx Estate.

By 1911, theatre bills advertised the Marx Brothers’ music and comedy routine. But while performing outside of Chicago, the Marx Brothers were transformed. According to good sources, while playing poker a fellow performer, Art Fisher, took it upon himself to give nicknames to each of the brothers corresponding with their personality traits and ending in an O.

Leonard was a womanizer who was popular with the “chicks,” so he became “Chico.” Arthur was an artist and musical talent who taught himself to play the harp and was known as “Harpo.” Julius Henry became Groucho for the grouch bag he wore around his neck that held his valuables. Milton was renamed Gummo for his sticky rubber-soled shoes. (Later in life, Groucho claimed his name came not from the pouch but because he was moody but not grouchy.) The story behind Zeppo’s name is a bit more complicated. According to Harpo’s 1961 biography, there was a trained chimp named Mr. Zippo. They gave Herbie the name Zippo because he liked to do tumbling and acrobatics, but he changed it to Zeppo.

The names stuck and the Marx Brothers became Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo, and Zeppo (Zeppo eventually replaced Gummo, who joined the Army). Each brother took on a persona that was easily identifiable to the audience. Groucho appeared with a greasepaint mustache and big cigar, launching quips and insults. Chico was a street-savvy Italian, and Harpo’s talents were based on pantomime and props, including his customary wig and horn.

Their first run on Broadway was in the summer of 1914, when they appeared on stage in the musical comedy Home Again. Their comedy was physical and filled with rapid-fire zingers; one newspaperman called them a “comic combustion.” While they prepared scripts for their acts, much of their work was done on the fly. Their form of comedy defined “improv!”

They continued to perform, but not until 1923 did they appear in a musical comedy they put together called I’ll Say She Is. Movies followed the stage acts, including hits such as Coconuts, Animal Crackers, Duck Soup, and Monkey Business. By the 1940s, their work had run its course and there were artistic differences with MGM studios. Their last film together was The Big Store in 1941.

Groucho went on to become the radio and then TV host for a quiz game You Bet Your Life. It ran from 1947 to 1961. The show was a good fit for the quick-witted barbs for which Groucho was famous. While their irreverent manner of comedy, physically and verbally insulting to some, fell out of favor, the anti-establishment movement of the 1960s brought their work back to light and today we still celebrate their comedic genius. For example, Marx Fest took over New York City in May.

We are honored to have Groucho and Harpo’s papers in the Archives Center of the National Museum of American History. The museum’s entertainment collection includes a suit worn by Groucho on You Bet Your Life, and a crazy collection of hats and wigs associated with Groucho.

This post was originally published by American History’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 2 June 2014

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture