The burning memory of a a “national calamity”

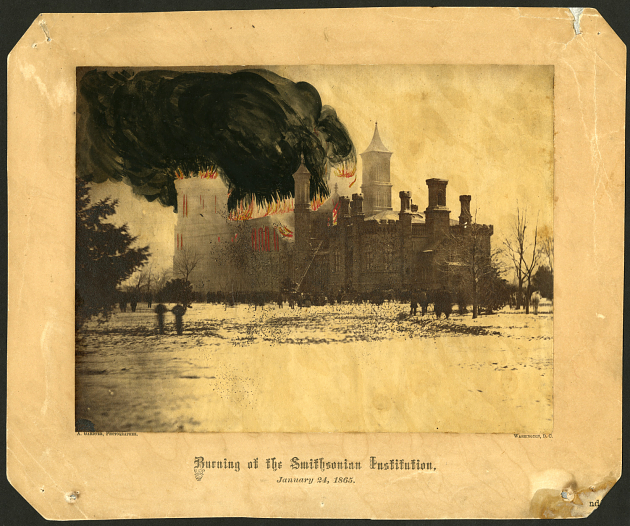

The Washington, D.C.-based photographer Andrew Gardner added hand-tinted flames to this albumen print, giving an impression of the fire that raged January 24, 1865. Smithsonian Institution Archives Neg. No. SIA2013-08351

It was a cold January afternoon 150 years ago this week. Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, was working in his office on the second floor of the building commonly known as the “Castle.” He was interrupted by a loud crackling sound from above and, looking up, quickly realized that the building was on fire. The blaze was the result of a stove that had been incorrectly installed in the Picture Gallery on the second floor. When it was all over, the damages to the Castle and its collections amounted to what The New York Times called a “national calamity.”

But not all was lost, of course. Today, objects and equipment that survived, and artifacts collected as a direct result of the fire, are housed throughout many of the museums here at the Smithsonian, where we still do our best to guard against fire, flood, and even earthquake. The National Museum of American History holds a number of objects that speak to the legacy of that tragic day as well as the resilience of the Institution.

Though Secretary Henry’s office was destroyed in the fire, along with much of his personal correspondence, some artifacts related to him, like this telegraph sounder, survived and were transferred to Smithsonian’s collections in 1895

This telegraph sounder was manufactured by Charles T. and John N. Chester of New York City, a firm that began making batteries and telegraphic equipment in 1855. The sounder is thought to have belonged to Joseph Henry as part of his experimental equipment while he served as Secretary of the Smithsonian. As such, it may well have been housed in the Castle building, where Henry both worked and lived, along with his family. Indeed, Henry’s pioneering work in electricity and electromagnetism in the 1830s was instrumental in the invention and development of the telegraph, as well as the electric motor and the telephone.

When it came to telegraphy, however, Joseph Henry was not only concerned with scientific theory. He was also a leading force behind the development of modern meteorology, and as Secretary, he created a network of over 600 volunteer weather observers through Central and North America who would send data to the Institution regarding local conditions. Their timely information was transmitted to Henry by—you guessed it—telegraph.

After its purchase in 1849, George Perkins Marsh’s extensive collection of European engravings, including this example, was made available in the Castle library. The collection drew attention, in the words of Assistant Secretary Charles Coffin Jewett, “not from undiscriminating idlers, but from men of taste and particularly from artists.”

This beautiful and detailed engraving, a version of the biblical scene of the adoration of the Magi by Hendrik Goltzius, dates to 1594. It came to the Smithsonian when the Institution purchased a large collection of fine art prints and books in 1849 from George Perkins Marsh, an American congressman, linguist, and diplomat who also served as a member of the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents. The engravings, numbering around 1,300 in total, constituted the first collection purchased by the nascent Institution and the first public print collection in the nation’s history.

In 1865, the print collection was held in the library, which was housed in the West Wing of the Castle, an area that was fortunately spared from damage by the fire, which was concentrated in the center of the building. Later that year, with the fire in mind, Secretary Henry deposited the Smithsonian’s library, along with portions of the Marsh collection, with the Library of Congress. Today, some books and prints from this pioneering Smithsonian collection are still held at the Library of Congress, as well as by the National Museum of American History.

Just six years before the fire, Joseph R. Priestley, grandson of the chemist Joseph Priestley, donated his famous grandfather’s burning lens and condensing air pump to the Smithsonian Institution. Secretary Henry, who was against the idea of the Smithsonian Institution becoming a national museum, nevertheless presented the objects to the Smithsonian Board of Regents as precious scientific relics. He described the lens as, “undoubtedly connected with the history of one of the most important chemical discoveries of the latter part of the last century,” referring to its use in the discovery of the gas oxygen. Sadly, as the apparatus room of the Castle went up in flames, so did Priestley’s lens and air pump.

Priestley, however, would once again find his place at the Smithsonian in 1883. After hearing of the death of a Priestley descendant, Secretary Spencer Baird (Henry’s successor) wrote to the surviving family members inquiring about the potential to donate more Priestley relics. The Smithsonian, he was careful to note, had recently completed the construction of a “thoroughly fireproof building” (today known as the Arts and Industries building) where the new donation could be stored.

Perhaps convinced that these objects wouldn’t also meet a fiery fate, the family agreed to the gift. Today, the gift, comprising more than 20 pieces of glassware and scientific instruments, remains an important part of the museum’s Chemistry and Electricity collections.

This post by Timothy Winkle, an associate curator in the Division of Home and Community Life at the National Museum of American History, and Mallory Warner, a project assistant in the Division of Medicine and Science, was originally published by American History’s blog, O Say Can You See? The Smithsonian Institution Archives has more about the January 24, 1865, fire on their blog and in historic correspondence.

Posted: 21 January 2015