Wilson A. Bentley: Pioneering photographer of snowflakes

“My collection [is] far superior in both number & beauty & I might add interest, to that of any other collection in the world…,” Wilson A. Bentley.

For over forty years, Wilson “Snowflake” Bentley (1865–1931) photographed thousands of individual snowflakes and perfected the innovative photomicrographic techniques. His photographs and publications provide valuable scientific records of snow crystals and their many types. Five hundred of his snowflake photos now reside in the Smithsonian Institution Archives, donated by Bentley in 1903 to protect against “all possibility of loss and destruction, through fire or accident.”

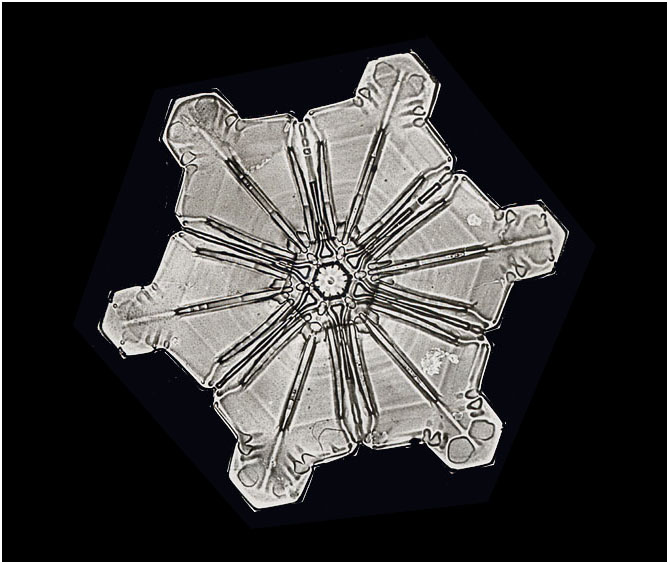

A Plate Snowflake, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 31, Box 12, Folder 17, Negative no. 801

Wilson A. Bentley was born in 1865 in Jericho, Vermont. Taught by his mother, he lived and worked on his family farm located in the “Snowbelt,” where the annual snow fall was about 120 inches. From the time he was a small boy, Bentley was fascinated by the natural world around him. He loved to study butterflies, leaves, and spider webs. He kept a record of the weather conditions every day and was fascinated by raindrops. Bentley developed an interest in snow crystals after he received a microscope for his fifteenth birthday. Four year later, in 1885, equipped with both his microscope and a camera, Bentley made the first successful photograph of a snowflake.

A Dendrite Star Snowflake, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 31, Box 12, Folder 17, Negative no. 332

Bentley was a pioneer in “photomicrography,” the photographing of very small objects, especially of snowflakes. Snowflakes or snow crystals are difficult to photograph because they melt so quickly. However, Bentley developed the equipment and techniques to take photographs of individual snowflakes. After many failed attempts at drawing the details of the snowflakes, he connected his camera to a microscope in order to create photos that showed intricate details of each snow crystal. Bentley stood in the winter cold for hours at a time; waiting patiently until he caught falling flakes. Once a snowflake landed, he carefully handled it with a feather to place it under the lens. The apparatus was set up outside so that the delicate specimens would not melt, and after a minute and a half exposure, he captured the image of a snowflake.

A Star Crystal Snowflake, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 31, Box 12, Folder 17, Negative no. 976

From that first photograph in 1885, Bentley photographed more than 5000 snow crystals until his death in 1931. From gathering this large collection of snowflakes, Bentley learned that every single snowflake was unique and in the year of his death he, along with William J. Humphreys, a physicist with the US Weather Bureau, published these findings in Snow Crystals, a volume containing 2300 of his photographs for all to study and enjoy. Throughout his life, he also published 60 articles in various scientific and popular journals. While most of his articles discussed snow crystals, he also photographed and wrote about frost, dew, and other atmospheric phenomena.

A Dendrite Star, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 31, Box 12, Folder 17, Negative no. 591

In 1903, he donated a collection of 500 of his snowflake photographs to the Smithsonian Institution to ensure their safety. In his correspondence with the Smithsonian Institution’s third Secretary, Samuel Pierpont Langley, Bentley offered positives and slides of his photos, writing that he was “deeply grateful for your [Langley’s] kindly help in thus placing my collection of snow photographs beyond all possibility of loss and destruction, through fire or accident.” At that time he also sent a copy of a previous publication on the snow crystal photographs. Later he sent a lecture he had given at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences in 1905, intending for it to be edited and published by the Smithsonian, though it never was. His photographs remain in the Smithsonian Institution Archives, safeguarded from any misfortune.

Bentley remained in Jericho, Vermont throughout his life. Ever dedicated to his work, he died there in 1931 after having caught pneumonia from walking through a blizzard.

This post was originally published by Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Bentley took tens of thousands of photos throughout his life, and his books catalog a decades-long parade of gorgeous, six-sided works of natural art. But his crystal-clear vision of reality was tied to a set of ideals that ultimately blinded him from the cold, hard facts in front of him. Snowflake expert and photographer Ken Libbrecht helps set the record straight in this podcast from RadioLab.

Posted: 19 February 2015

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Science and Nature