An international endeavor

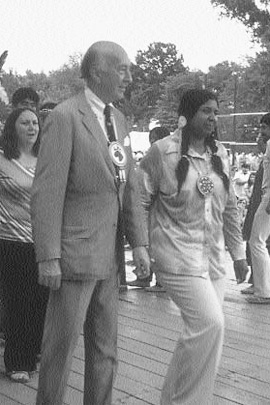

Secretary S. Dillon Ripley championed the Smithsonian Folklife Festival as a way to highlight the importance of cultural preservation.

British scientist and our original benefactor James Smithson never set foot on our shores. Yet he entrusted our young nation with his fortune to create this Institution devoted to the “increase and diffusion of knowledge.” Inspired by the Enlightenment thinkers of the time, Smithson thought scientists should aim to be “citizens of the world,” seeking truth wherever it presented itself.

Driven by the same curiosity about the natural world, a group of civilian “scientific corps” joined the U.S. Navy’s four-year Wilkes expedition in 1838, scouring the world for samples of botany, zoology, and anthropology, among many others. The vast array of specimens they gathered formed the basis of the Smithsonian’s scientific collections, and the knowledge they amassed added to understanding the oceans, the cosmos, and the weather. From its inception, the Smithsonian has always been an international Institution. Our first Secretary, Joseph Henry, noted this when he commented that limiting the scope “to one city, or even to one country,” would be “an invidious restriction” of the Institution. Our intrepid Smithsonian explorers often go to the ends of the earth to fulfill our mission, whether in science, art, history, or increasingly, to preserve cultural heritage.

Throughout the world, art, artifacts, and architecture hold the key to cultural identity. Natural disasters and political instability threaten that identity. As former Smithsonian Secretary S. Dillon Ripley noted of traditions and cultures, “They are being eroded every day just as the forests of the tropics disappear.” The Smithsonian has a number of ongoing efforts to help prevent the erosion of past and present cultures by protecting the historic objects that tell their stories.

The Smithsonian’s Cultural Heritage Preservation Specialist, retired Army Reserve Maj. Cori Wegener, has worked on the front lines from Haiti to Syria to address threats to cultural heritage, and plans are in the works to expand our capacity in that regard. Recently the Smithsonian hosted the National Conference on Cultural Property Protection to discuss best practices for protecting our vital cultural treasures. It was truly international as participants from Canada, South Korea, the Netherlands, the U.K., Belgium, and Egypt took part. The Office of International Relations recently coordinated with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and USAID to protect and promote the traditional culture of ethnic Tibetan communities in China, including language, visual and performing arts, and historic sites.

Haitian artists restoring a earthquake-damaged masterpiece under the supervision of Stephanie Hornbeck and Rachel Goslins of the Haiti Cultural Recovery Project. (Photo by Wayne Clough)

A kindred spirit in our efforts, the Prince of Wales, came to the Smithsonian on March 18 to tour the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. His non-profit foundation, Turquoise Mountain, works to promote Afghanistan’s arts and crafts and rebuild Kabul’s Old City. In March 2016 the galleries will partner with Turquoise Mountain to put on an exhibition of Afghan art.

Though a visit from His Royal Highness does not happen often, every summer since 1967, roughly one million people flock to the National Mall to enjoy the international flavor of the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. In June, this year’s featured country of Peru will be represented in music, dance, food, and crafts. In addition to the Festival, Peru is featured in another big Smithsonian event, the exhibition “The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire,” at the National Museum of the American Indian, which opens June 26, 2015 and runs through June 1, 2018. Through these two events, visitors will get to experience firsthand the importance of Peru’s culture, learn about its long history of advanced engineering that is still relevant today, and appreciate the rich biodiversity that spawns scientific discoveries.

From left, Julian Raby, the Dame Jillian Sackler Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art; The Prince of Wales; and Shoshana Stewart, CEO of Turquoise Mountain (photo by Neil Greentree)

And, as James Smithson envisioned, our footprint in science is truly global. On March 16, the Smithsonian and Nanyang Technological University of Singapore signed a Memorandum of Understanding to collaborate on scientific research and education in forest and marine tropical ecology and global environmental change. It is only one of the multitude of international agreements we have that allow us to expand our scientific reach, from our Global Tiger Initiative partnership with the World Bank to vector-borne disease study in Africa and Asia.

Our scientists travel far and wide, and we have forged countless international partnerships, but never before have we ventured overseas in the same way envisioned with “Olympicopolis.” It is part of a wide-ranging project of economic development, social revival, and cultural renaissance located at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in London. If we reach an agreement with the city of London, the Smithsonian would have a 40,000-square-foot gallery, our first long-term exhibition space outside the U.S.

With activities in more than 130 countries and students, teachers and lifelong learners all over the world accessing our online educational resources, the Smithsonian is becoming an ever bigger player on the international stage. We aspire to do more and live up to James Smithson’s legacy. As the world flattens, cultural diplomacy is more important than ever before to open up dialogue among countries across the globe. The Smithsonian represents the best of what America has to offer the world, and we will continue to live up to the Enlightenment ideals that are a foundation of the Institution and the nation.

Posted: 30 March 2015

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , From the Secretary , History and Culture