Why is some mid-century art cracking up? A Smithsonian conservator cracks the case.

Example of cleavage between cadmium colors painted over zinc oxide oil paint in Hans Hofmann’s “Trophy/Verso: Untitled,” from 1951. (Photo by Dawn Rogala)

Who doesn’t love trying something new? In the mid-1900s a number of modern artists experimented with new types of commercial paint using it as a base layer for their paintings. Now, decades later, their paint choices are turning out to have some negative consequences.

Abstract Expressionist painters Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock and others took advantage of an explosion of new paints, including zinc oxide and commercial white house paints, that became available in the years following the first and second world wars.

The new whites were an alternative to the lead-based whites many artists had traditionally used for the underlying base layer of their paintings, a choice that freed them from the chore of grinding and blending their own paints. But they didn’t know the exact composition of these new paints or how they would behave over time, sandwiched between a piece of stretched canvas and layers of colorful oil based artists’ paints.

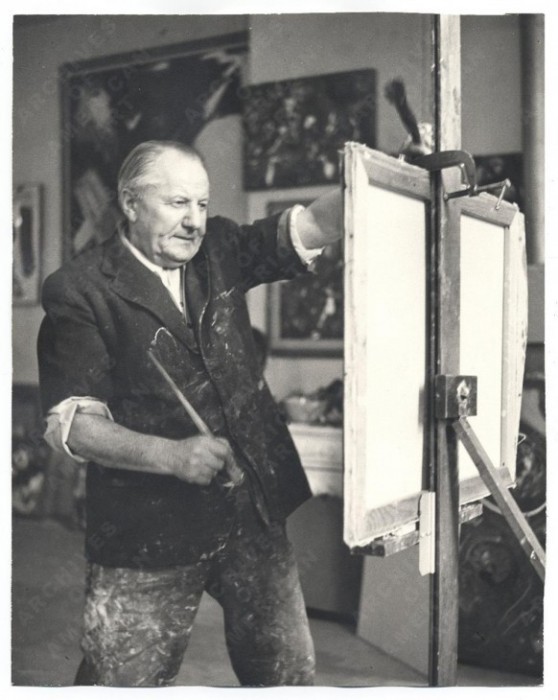

Hans Hofmann at work in his studio, 1952. Kay Bell Reynal, photographer. Courtesy Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

“Here are these new paints that everyone is playing with,” says Dawn Rogala, a paintings conservator at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute. “Formulated with new materials and new technology, there were a lot of unknowns about these paints that the artists were not aware of then and that we’re still learning about today.”

Rogala noticed an unusual pattern of cracking and lifting in some mid-20th century paintings in the collection of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. She used painstaking scientific analysis to find out why these paint layers were lifting and separating, building on previous research she’d done on works by Hans Hofmann, a central figure of the Abstract Expressionist movement of the 1940s and 1950s.

Rogala analyzed more than 500 paint and fiber samples through spectroscopy and spectrometry. She confirmed that in paintings with a cracking foundation layer, the white paint was either brittle zinc oxide or commercial house paint. Both paints were never engineered to support the heavy paint layers used in some modern fine art paintings.

Dawn Rogala used her colleague Marion Mecklenburg’s paint samples, or drawdowns, at the Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute as part of her recent work on condition issues in several mid 20th-century paintings. (Photo by Michelle Z. Donahue)

Traditional oil-base fine-art paints form a sturdy cross-linked structure as they cure; their molecules bonding tightly together. Zinc whites cure into a series of very thin layers of stiff plates. In commercial house paints, the problem is that they are “under bound” with too much pigment and too little binder to hold it all together. As mid-1900s house paints cure and are subject to stress, they form a series of tiny cracks or micro fissures.

As the base layer of a canvas, zinc oxides and house paints can’t hold up under the strain of thick, heavy layers of oil paints. They dry into plates that separate from themselves under stress, Rogala found.

“When a crack starts opening up, there is a lot of stress at the edges, and they kind of unzip,” Rogala explains about the zinc base paint layers.

Marion Mecklenburg, senior research scientist emeritus with the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, researched this kind of stress and strain in aging paints over decades. His work shows that zinc oxides and house paints, when under stress, crack before nearby layers of paint. The stretching and shrinking of a canvas caused by fluctuations in humidity or jostling from being moved causes such stress.

Fixing paintings with cracking base layers takes time, Rogala adds. “If you have some flaking, and the ground layer is zinc white or house paint, it can indicate a bigger problem. We need to carefully watch these works to ensure their preservation.”

Cleavage between the ground (seen as the open white patch) and mixed layers of oil paints in Hofmann’s work “Trophy/Verso Untitled,” painted in 1951. (Photo by Dawn Rogala)

This post by Michelle Z. Donahue was originally published by Smithsonian Science.

Posted: 15 April 2015

-

Categories:

Art and Design , Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , Hirshhorn Museum