Depicting the Business of Slavery

In the wake of this week’s horrific racist hate crime in South Carolina, “Juneteenth” is a sadly ironic day to reflect on the economic and cultural legacy of the business slavery.

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, and issued General Orders, Number 3, which proclaimed that all slaves in the state were free, and that there now existed “an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” While the Emancipation Proclamation had technically ended slavery in Confederate states more than two years earlier, the arrival of Granger’s army finally made freedom a reality for many enslaved men and women. In the years that followed, growing numbers of black Texans set aside June 19th as a day to celebrate emancipation. Their celebrations created the foundation for Juneteenth, which has grown from a local holiday in Texas to one of the United States’s most popular holidays celebrating the end of slavery.

Relatively few histories mention that, after announcing “absolute equality,” General Orders Number 3 also mandated that the “connection heretofore existing between” masters and slaves would now become “that between employer and hired labor.” For the first time, former slave-owners could no longer claim that other human beings were their personal property. Today, one-hundred and fifty years later, this passage reminds us that slavery was a fundamentally unjust system of labor, one that had a profound influence on the U.S. economy from the nation’s founding through the Civil War. Slavery created enormous profits not only for Southern planters and slave traders, but also for Northern cotton-mill owners and investors. Nearly one million enslaved African-Americans, defined as property, were sold in the interstate slave trade, wrenched from their upper South families, and forced to work in the plantations and factories of the lower South.

The American Enterprise exhibition, opening July 1, 2015 in the Mars Hall of American Business, will give visitors an opportunity to learn about the economic dimensions of slavery and reflect on the institution’s social and personal costs. Jordan Grant, a New Media Assistant working with American Enterprise, sat down with Smithsonian curator Nancy Davis to learn more about this section of the exhibition.

What exactly was the “Business of Slavery,” and how does it fit into the larger history of business in America?

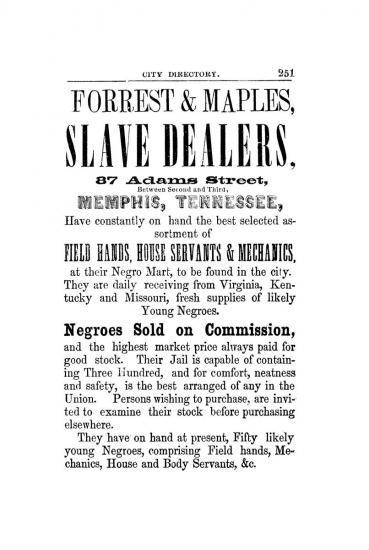

The buying and selling of enslaved peoples as property was a huge business—one that took advantage of all the business innovations that any other sort of business in the 1800s was engaged in. The larger slave trading businesses embraced a strategy of vertical integration, eliminating middlemen to greatly increase their profits. These firms owned their own sea-faring vessels to transport slaves from the upper to the lower South, and they established their own jails and complexes for holding slaves for sale; they controlled every aspect of the sale. But slave trading was only a part of the business—the cost of insuring slaves and the property taxes levied on them were business aspects that we often ignore. And of course, the largest aspect of this big business was the profit gained by southern cotton planters for whom the enslaved labored, and the northern and British owners of cotton mills that rolled out the products from their labor.

What are some of the difficulties that you and the rest of the exhibition team faced when taking on this difficult piece of American history?

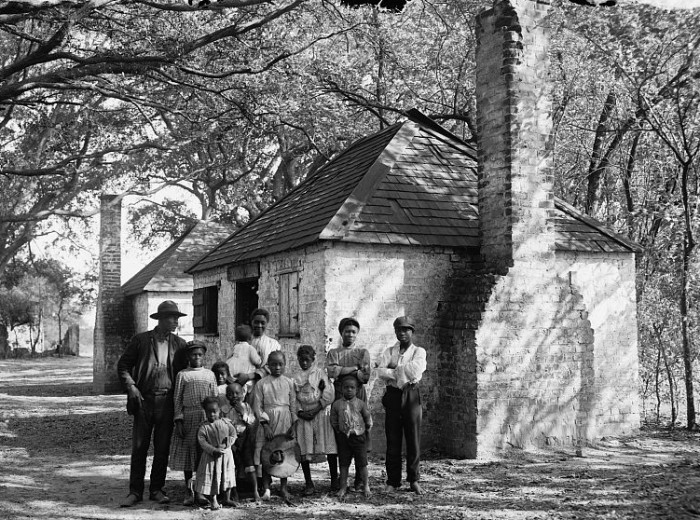

When we considered what objects might tell this particular story of capitalism and slavery, we found there really were very few that could be easily displayed. The business of slavery produced an enormous amount of paper—receipts, notes, insurance forms, tax documents—but paper documents, sensitive to light exposure, could not be left on permanent display. More importantly, we realized that the only way to get at the issues of property and the reprehensible aspects of owning people as property was to convey that story through the conceptualization of people themselves. The challenge of balance, how to convey this concept and yet give agency to the enslaved, was extremely difficult. Eventually, we decided to create a sculpture with three figures—a husband, a wife, and their child—and focus visitors’ attention on a story at the heart of the business of slavery—the wrenching apart of families. Instead of placing the family at an auction block, or in another familiar scene, we chose to portray them as they would have appeared on their plantation home in the upper South. In the scene depicted in the exhibition, the parents had no warning when slave traders came for their son. The base that the figures are standing upon is literally splitting apart, separating the family, and the base of sculpture bears the names of men and women who were sold in the interstate slave trade. We intend the depiction to be heart wrenching because it was.

I understand the section includes an interactive station where the people can dig deeper into the “Business of Slavery.” What will visitors be able to do in this interactive?

The interactive display will let visitors explore several different documents related to the business of slavery, including a bill of sale, a tax receipt, an insurance document, and a ship’s manifest. People will be able to decode these documents and, in the process, learn more about the lives of the enslaved. The interactive also helps us tell complex stories. For example, one document is an insurance policy that the slave-owner Monroe Frankling Vaiden took out for the life of William, a enslaved man in Charles City, Virginia. Through this document, visitors can learn that, while Northern insurance companies did not own slaves, they were complicit with slavery and profited from treating people as property.

Can you tell us about who you worked with to develop this part of the exhibition?

We worked closely with scholars, artists, actors, museum colleagues, and graduate students in museum studies throughout the process, often in surprising ways. For example, it was very difficult to define the period-appropriate clothing for the husband, wife, and child. We were fortunate enough have the assistance of Dr. Katie Knowles, an expert on slaves’ clothing, who was serving as a fellow at the museum, and with her help we were able to answer questions like, “What kind of shoes would an enslaved man wear?” or “What sort of head garb might an enslaved woman wear?” The sculpture of the enslaved family is actually based upon real-life actors. Our exhibition team went through several Skype sessions (the artists were based in New York) where we worked with the actors to find just the right pose for the scene.

Are there any standout stories or examples from this section that you could share with readers?

I find the stories of the enslaved individuals in the interactive the most poignant. Nate, William, Matilda and Moses: these were real people noted in real documents. The research on their lives took an enormous amount of time, as did the research we did to find the names of the men and women listed on the plinth (upon which the sculptures stand), all of whom had been enslaved and sold to the deep south. In many cases, the only record we have of these individuals’ lives are the names that were saved on a bill of sale or a ship’s manifest. It was also particularly difficult for me to work with the small boy who served as one the actors for the scene depicted in the exhibition. I felt for him as he recreated the moment of separation, which I think he actually felt as he portrayed it.

What do you hope visitors will learn or experience?

I hope visitors will be gripped by the moment and in that moment will consider the impact slavery had on so many. I hope that they will understand the larger concept of this period, beyond what we generally know of slavery, and that they will also wrestle with the concept of people as property from this time period—a reprehensible and repugnant dark side of capitalism which we do not hide but can fully discuss, react to, and learn from today.

This post was originally published by the American History Museum blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 19 June 2015

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture