Why the arts matter: Our future may depend on our creativity

Our new Secretary, Dr. David Skorton is many things: educator, cardiologist and avid amateur jazz musician. When he isn’t practicing the flute or saxophone, he is championing the arts because, as he has noted, “Our nation’s future may depend on our creativity.” Dr. Skorton comes to the Smithsonian with a well-earned reputation as an advocate for the arts. He sat down with the Torch to explain what the arts mean to him and why the arts and humanities are such a vital part of the Smithsonian’s mission.

Megatron/Matrix (1995) by Nam June Paik Born: Seoul, Korea 1932 Died: Miami Beach, Florida 2006. Eight-channel video installation with custom electronics; color, sound. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

How do you define “the arts,” and why do you think the arts are important? How do the arts help with creative thinking in all fields of endeavor?

I define the arts broadly as the human expression of creativity related to culture, including all the visual arts, performing arts and creative writing. (I plan to discuss the creativity involved in scientific research and discovery in a future column.) The arts are not only important but critical, providing tangible aesthetic and economic benefits to individuals and society as a whole. For example, in the U.S. alone, the arts inject nearly 700 billion dollars into the economy annually. The arts also inspire creativity that drives innovation in science and technology—it is why so many inventors and innovators have had artistic sides, from Leonardo da Vinci to Samuel Morse to Rosalind Franklin to Edwin Land. But most important, the arts are the distillation of our intrinsic need to express and understand ourselves and to understand other peoples and cultures across the world. Simply put, poetry, dance, music, and the visual arts enlighten, educate, and inspire us and spur the creativity that is uniquely human.

You are known for your work in medicine and higher education. What led you to begin promoting the arts so vigorously?

I had a broad liberal arts education and that had something to do with it. But long before my higher education, I had the example from my parents—neither of whom went to college—who expressed creativity through sketching, ceramics and design. Also, I grew up aspiring to be a musician, even though I finally realized that music would be a hobby and not a career.

What role does the Smithsonian play in bringing the arts to the world, and how would you like to see that role expanded?

The Smithsonian plays an enormous and multifaceted role by recognizing, gathering, understanding, preserving, disseminating and celebrating arts of all kinds. Our role to increase and diffuse knowledge in the arts is equally robust as it is in the sciences. I will continue to promote this aspect of the Smithsonian and find ways to work within our walls and with external partners to fortify our arts presence locally, nationally and abroad.

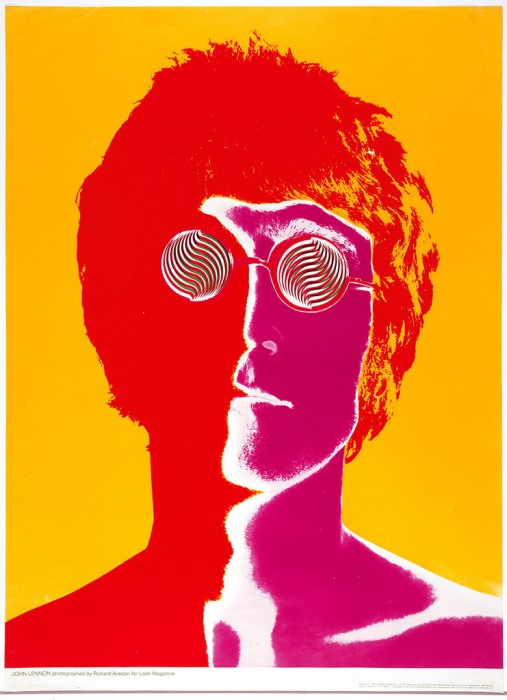

Poster of John Lennon (1967) designed by Richard Avedon for Richard Avedon Posters, Inc. Acquired by Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through various donors in 1981.

What artistic activities and holdings were you surprised to find at the Smithsonian?

I was well aware of the excellence of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the excitement of the National Portrait Gallery, the innovation of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the inspiration of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, the dynamism of the National Museum of African Art, and the elegance of the collections in the Freer and Sackler Galleries. What I didn’t fully appreciate was the magnitude of the breadth and depth of our arts that are showcased beyond our art-specific museums, from the National Air and Space Museum’s sizable art collection to exhibitions of contemporary creations of Native people in the National Museum of the American Indian, from ethnographic art in the National Museum of Natural History and stamp art at the National Postal Museum to the growing collections of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture, from the tremendous musical instrument collection at the National Museum of American History to the diverse display of performances at the annual Folklife Festival and on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. And just southeast of the National Mall at the Anacostia Community Museum, everything from quilting to poetry is explored. Nor did I know what an incredible scholarly resource the Archives of American Art is, with more than 20 million records of the visual arts in America in its collections. The performing and visual arts are really everywhere you look at the Smithsonian—and around the world as well because we work with colleagues to preserve arts threatened by natural disasters such as those in Haiti and Nepal, and by human conflict in places such as Iraq, Syria, and Mali.

At Cornell, you made your interest in poetry known. A book of poetry was compiled for you by the poet Alice Fulton. You and your wife wrote haiku each year for the winter card you sent to campus and alumni. Now you display a “Poem of the Week” in the Secretary’s office, including “Word Cloud over Gettysburg,” written by David Ward, senior historian National Portrait Gallery. Why does poetry speak to you?

Poetry speaks to me as do all the arts. The range of creativity expressed by poetry, from traditional to modern, is breathtaking. Like all good art or literature or music, poetry is insightful and thought provoking. It reveals new ways to look at the world. David Ward has a great piece in Smithsonian magazine on Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” that speaks to the power of poetry, and David’s analysis made me take a second look at a poem I thought I knew.

The Mickey Hart Collection from Smithsonian Folkways preserves and furthers the Grateful Dead percussionist’s endeavor to cross borders and expand musical horizons. Six of the 25 albums in the collection form the “Endangered Music Project,” a collaboration between Mickey Hart and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, which presents recordings from musical traditions at risk.

What do you say to those who contend that the arts are a luxury and that we should focus our attention on STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education?

I try to make two points: First, STEM is hugely important, but a life in medicine and science has taught me that we cannot solve or even comprehend all of our problems with science alone. Most important, these areas of human creativity are not and should not be in some sort of competition. What better place than the Smithsonian to make clear that the arts and science go hand in hand, and that both are important for learners of all ages and to society as a whole. Maria Mitchell, America’s first female astronomer, whose telescope is in the collections of the National Museum of American History, had it right when she said, “We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.”

Despite your modesty, your jazz skills are well known, as is your propensity for playing with some big-time artists when the opportunity presents itself. Is it true you are going to play with our own Jazz Masterworks Orchestra on October 17?

I am humbled to have been asked to perform with this group of musicians whom I have followed and admired. It will be a stretch for me to be part of that terrific group. Let’s hope they don’t regret asking!

How did playing jazz help your leadership skills?

Part of the essence of jazz is personal creativity (the solo), realized in the context of the overall music being played by the entire group (the harmonic progression). Leadership should stress that harmonization of individual creativity in the context of group cohesion. Easy to say, hard to do.

What do scientists and artists have to learn from one another? Do you want to see them working together more here at the Smithsonian?

Scientists and artists share many traits: curiosity, creativity, innovation and a desire to understand the world within and around us. In the 21st century, we need to all be more nimble, creative thinkers and work together if we are to solve our most pressing challenges. The Smithsonian increasingly works collaboratively inside and outside the Institution, and I hope to foster even more of that.

Your 2006 Cornell inaugural address revolved around the theme of dance. Is that another of your talents? Can we expect to see you on Dancing with the Stars someday soon?

I can safely predict that you will not see me anywhere near that show, for lack of courage and skill. Otherwise, I’d be there for sure.

Posted: 31 August 2015