Poking fun at the crowded presidential race—in the 1880s

Anyone who pays attention to politics knows that this Presidential campaign season has been unusually crowded and contentious. Jon Grinspan of the American History Museum reminds us that is it was ever thus.

The amazing thing about running for president is how many people are actually willing to attempt it. The 2016 campaign’s big crop is nothing new—throughout American history large numbers of contenders have crowded into the ring. And though the forty-one-candidate Democratic primary of 1924 seemed to have had the most aspirants, the campaigns of the late 19th century struck citizens as the most overstuffed.

And the most ridiculous.

In the 1880s, Americans chuckled at the self-importance of the many men who thought they should be president. Campaigns were intense—marked by the highest turnouts and closest elections in U.S. history. And after two assassinations, one impeachment, and one contested election in just sixteen years, politicians looked painfully human. With the dramas of the Civil War and Reconstruction receding, it was clear that there were no new Lincolns on the horizon.

Finally, Americans had become adept at mocking their political system. Punchy, irreverent magazines like Puck and Judge refused to let any would-be candidate preen for public attention.

Puck’s cartoonists began laughing at 1884’s potential candidates way back in 1882, mocking the “Premature Snowball-Rolling” of politicians who imagined themselves winning the election “three hot summers” away.

This snarky cartoon is packed with little jokes and jibes that are arcane today, but would make your average Gilded Age American chuckle. The disgraced political boss, Roscoe Conkling, known for his haughty, overdressed style, is depicted wrapped in a woman’s coat, muff, and hat. Poor old Samuel Tilden—who won the popular vote for president in the contested 1876 but never got to hold office—shivers pathetically in the background (comforted by Rutherford B. Hayes, the friendly guy who stole that election). And the cartoonist mocked George Francis Train—an attention-seeking oddball who called himself “the Great American Crank”—rolling his never-ending letters to the press, instead of snow.

The White House is clearly a long way away.

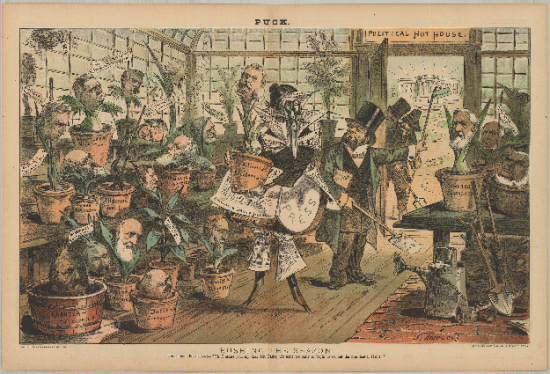

Later that year, Puck has even less reverence for the many politicians “rushing the season.” Each of the plants in the “political hothouse” contains a snarky little dig at a potential candidate. Ulysses S. Grant—who had already served twice as president and kept rumors swirling about a third run, is an overgrown bulb. Puck mocked then-president Chester A. Arthur—in power merely because James Garfield was assassinated—as part of the genus “Accidentalia.” And the cartoonist goes after Roscoe Conkling again, labeling him “Shotgunonia,” in a sly reference to the incident in which his mistress’ husband threatened him with a loaded shotgun.

At the center of this cartoon is a monstrous gardener—”Mr. Press”—prematurely beginning the campaign at the urging of out-of-work politicians, ready to demand cushy political offices from these unripe candidates.

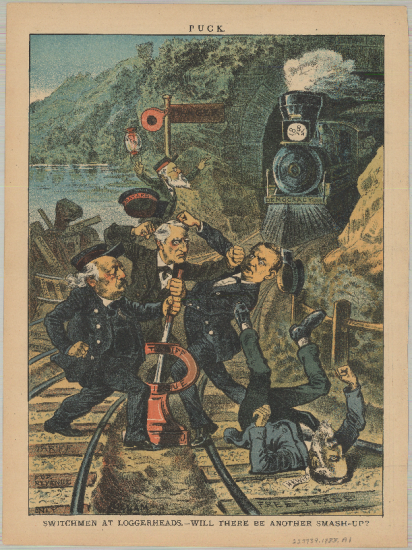

By the start of the real campaign, in 1883, the election is no distant goal—suddenly 1884 is a speeding locomotive, bearing down on bickering politicians. In this cartoon, Puck mocks the Democratic politicos squabbling over the direction of their party. It shows Pennsylvania Congressman Sam Randall and Delaware Senator Thomas Bayard—both closely tied to thuggish, violent party bosses—grappling. New York politician Abram Hewitt—widely respected as an honest, well-intentioned, moderate reformer, lies on the ground, knocked out by his sleazier rivals.

The message of all these cartoons, mocking at least two-dozen prominent politicians, is that running for the presidency is always a bit ridiculous. It’s a big jump, even in that era of powerful senators and weak executives, to try to move into the White House. Most presidential candidates—with the possible exception of George Washington—have seemed unfit for the job at first, at least in certain ways. And as more would-be presidents crowd into the race, the sillier they all seem.

Something else is noticeable. The man who would actually win the White House in 1884, Grover Cleveland, does not appear in any of these cartoons. In the long, complicated process of winning the presidency, no one can ever be too certain who will come out on top.

Jon Grinspan is the Jefferson Fellow in the Division of Political History. This is an edited version of a post originally published by the American History Museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 18 September 2015

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture