Welcome to The Conversation’s series on thalidomide – the history of the tragedy, its long-term impacts and the fight for justice. In this longer read, medical historian Arthur Daemmrich sets the scene of the mid-20th century drug landscape and explains how thalidomide was marketed, used, and withdrawn after causing thousands of birth defects.

![]() Thalidomide was developed in an era of widespread enthusiasm – but little critical attention – for pharmaceutical therapies.

Thalidomide was developed in an era of widespread enthusiasm – but little critical attention – for pharmaceutical therapies.

Starting with penicillin in the 1940s, researchers discovered dozens of broad-spectrum antibiotics in soil samples around the world that could be inexpensively manufactured. This meant infectious diseases that had plagued mankind for centuries were now amenable to treatments lasting a week or less. Public excitement for medicine’s advances ran high in this so-called medicinal “golden age.”

The introduction in 1954 of the antipsychotic medicines chlorpromazine and reserpine (sold under the brand names Thorazine and Serpasil) signalled a major therapeutic shift for mental and behavioral disorders.

Physicians in academic hospitals were initially reluctant to use them, concerned that treating symptoms did little for underlying disorders. But within a few years, tranquilizers and antipsychotics gained wide acceptance in the treatment of severe mental disorders. Hospitals reduced the use of electric shock and insulin treatments by 90% and lobotomies fell out of favor almost entirely.

US National Archives and Records Administration, CC BY

The tranquilizer meprobamate (sold under brand names Miltown and Equanil) was first marketed in 1955 to treat less severe mental and emotional conditions, notably anxiety and stress.

Miltown quickly became iconic in American life. Within months, it was the best-selling drug in the country and by 1957, one-third of all new prescriptions were for Miltown or Equanil.

At the time, pregnant women were medicated with both sedatives and stimulants. A 1956 study of first-time mothers at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York reveals that all 50 research participants were on a mix of sedatives, hypnotics and tranquilizers while giving birth. Researchers reported sedatives were suitable for use in pregnancy to treat sleeplessness, morning sickness, and severe nausea and vomiting.

Medical experts began to interrogate this enthusiastic prescribing and patient demand for antibiotics, stimulants and depressants from the late 1950s. More sustained criticism of excessive tranquilizer and sedative followed in the 1960s, when evidence emerged that users of meprobamate and other minor tranquilizers suffered withdrawal symptoms in the form of anxiety, irritability, insomnia, headaches, and depression when they stopped taking the pills.

Thalidomide’s safety testing

Thalidomide was first synthesized in March 1954 by chemists at Chemie Grünenthal (Grünenthal), a small pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturer in northwestern Germany.

Paul Townsend/Flickr, CC BY-ND

Laboratory and animal test results were first published in 1956 and showed the drug had a low toxicity. Standard toxicity tests at the time involved dosing mice until half of the population died. This determined a “lethal dose 50”, or LD50, level. For thalidomide, no toxic effects were found at even 5,000 milligrams per kilogram of body weight in mice.

Others tests in mice and rats, including cardiac, blood pressure, respiratory, urine secretion, temperature, and basal metabolic rate showed no harmful affects.

From 1956, scientists tested the drug on healthy adults, patients complaining of anxiety or sleeplessness, nursing mothers, patients with mental illnesses, and children. Studies published in German medical journals reported participants were pleased with thalidomide’s sedation and suffered almost no hangover effects or other side effects.

Grünenthal continued to sponsor research into the drug through at least 1960. However, no physician in Germany or elsewhere running clinical trials of the drug appears to have observed or drawn a link to birth deformities.

From flu to morning sickness

Grünenthal began to market the drug in November 1956 under the brand name “Grippex” as a treatment for the common flu (seasonal flu is called “Grippe” in German).

Author provided.

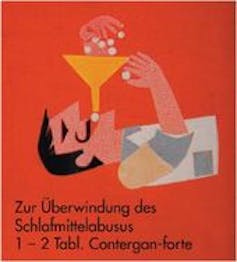

In January 1957, the company began marketing the drug as “Contergan” for daytime use to reduce stress and anxiety, and “Contergan forte” as a sleep aid. Contergan was rapidly taken up by consumers.

Post-war Germany was enjoying rapid economic growth, but also rising stress associated with a transformed economy and cold-war divisions of the country. Facing few competitors, thalidomide became the country’s top sedative, with sales five times those of its leading competitor.

Taking thalidomide to treat nausea during pregnancy appears to have spread among physicians and pregnant women in West Germany during the first half of 1959. Regional variation in the number of children born with deformities suggests the practice was not universal across the country.

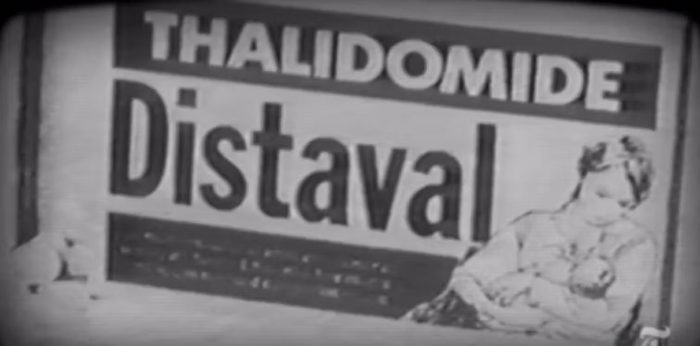

In the United Kingdom, Distillers Ltd. licensed thalidomide and began selling it as Distaval in April, 1958. Other companies licensed and sold the drug worldwide in the late 1950s under dozens of different brand names.

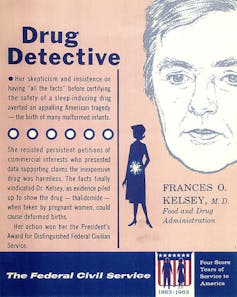

US FDA, CC BY

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received an application for thalidomide (under the brand name Kevadon) on September 12, 1960. Its review was assigned to Frances Kelsey, a new employee who pressed the company for additional data. However, Kelsey delayed approval until the adverse reactions became widely known.

The separation between specialists in psychiatry and pediatrics – and the lag time between exposure to thalidomide in the first trimester of pregnancy and impacts on a child being visible only after birth – contributed to the delays in identifying the crisis.

Side effects

In early October 1959, almost three years after thalidomide came on the German market, neurologists Ralf Voss and Horst Frenkel saw several patients who complained of numbness in their hands and feet, and pain from nerve inflammation. They reported on cases of peripheral neuritis (nerve inflammation) associated with thalidomide at a 1960 conference of the German Society for Neurology.

Warning labels were subsequently added to packs and some German states moved to prescription-only sales of Contergan and Contergan forte.

Author-provided.

The first reports of a new wave of deformities in children were made at a German Pediatric Society meeting in October 1960. Physicians Wilhelm Kosenow and Rudolf Pfeiffer described two infants with unusual congenital defects and showed X-ray films of their deformities. But they did not suggest a cause.

In September, physician Hans-Rudolf Wiedemann published an article describing 27 cases of infants with deformities to their arms, hands, legs, feet, and internal organs. He warned of a rising incidence that he feared was similar to a contagious disease epidemic.

After encountering several cases in his practice, the pediatrician Widukind Lenz surveyed the rate of new birth defects in the Hamburg region and found 50 cases. Lenz then went through city records of all births from 1930 to 1955, and found only one similar recorded case.

Because the deformities appeared suddenly and had diverse physical manifestations, physicians generally ruled out genetic causes. Instead, German pediatricians initially suspected an environmental factor was to blame, perhaps nuclear radiation or an unreported chemical spill.

Otis Historical Archives National Museum of Health and Medicine, CC BY

However, Lenz began to ask mothers about drugs taken during pregnancy, and soon identified four cases involving Contergan or Contergan forte. By mid-November, he had identified fourteen additional cases where mothers remembered taking thalidomide.

Lenz phoned Grünenthal’s research director Heinrich Mückter on November 15 and warned that thalidomide might be the cause of deformities in children.

Pfeiffer and Kosenow presented findings on cases of limb deformities at the November 19, 1961 meeting of the Rheinish-Westfälischen Kinderärztevereinigung (Association of Pediatricians in Rhineland–Westphalia).

Following their presentation, Lenz stated publicly a specific drug was to blame. On November 26, the weekly newsmagazine Welt am Sonntag reported on Lenz’s presentation at the pediatrician meeting and called for the still-unnamed drug to be withdrawn.

Market withdrawal

The next day, Grünenthal withdrew all medicines containing thalidomide from the German market. Five days later, on December 2, Distillers withdrew Distaval, as well as four other drugs that contained thalidomide from the UK market.

On December 16, 1961, the first English-language medical journal reference to unusual phocomelia cases (malformation of the limbs) was published in the form of three short paragraphs in the “letters to the editor” section of The Lancet, by Australian gynecologist and obstetrician William McBride.

On January 6, 1962 two additional letters were published. The first, from Widukind Lenz, stated he had seen “52 malformed infants whose mothers had taken Contergan in early pregnancy”. The second, from Pfeiffer and Kosenow, sought to characterize and categorize the congenital deformities based on the cases they had witnessed.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Several weeks later, in early January 1962, Lenz published an article in The Lancet about 50 cases he had directly observed and referenced an additional 115 cases from Germany, Belgium, England, and Sweden which were thought to be caused by Contergan.

Other market withdrawals ensued over the course of 1962, extending through mid-May, when licensee Dai Nippon withdrew it from the Japanese market.

On March 13, 1967, the state prosecutor for North Rhine–Westphalia issued a criminal complaint against 18 executives and scientists from Grünenthal.

The “Contergan trial,” as it was termed, began in January 1968 and ended two-and-a-half years later after 60 experts and 120 witnesses provided reports, testimony, and underwent cross-examination.

However, state prosecutors ultimately dropped all charges in exchange for Grünenthal’s agreement to establish a fund for injured children that had additional financial support from the government. In the final written decision, the court ruled that thalidomide had caused congenital deformities, but this could not be predicted, based on testing practices common at the time.

Aftermath

Thalidomide use in the late 50s and early 60s caused some 10,000 children worldwide to be born with significant birth deformities. Although it would take another decade or more in some countries, perceptions of “normal” bodies eventually broadened and efforts were made to accommodate people whose bodies do not conform to previous norms.

The tragic case was a significant historical turning point in drug testing and regulatory oversight. Although many of the changes to drug testing and regulation attributed to thalidomide were already underway in the 1950s, new regimes ultimately contributed to greater confidence that thalidomide’s uses today for cancer and leprosy would not again cause a medical tragedy.

Author: Arthur Daemmrich, Director, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, Smithsonian Institution

Welcome to The Conversation. The Conversation U.S. is an independent, non-profit news organization that publishes evidence-based, explanatory articles written by scholars, edited by experienced journalists and delivered directly to the public in plain English.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Learn more on The Conversation’s website and see a full list of articles written and published by Smithsonian scholars.