Collecting history as it happens at the 2016 political conventions

Delegates may go to political conventions to support their candidate, partisans may follow them on social media to share the next viral meme, but Political History curators have an agenda all their own when it comes to the conventions.

NEW YORK – SEPTEMBER 02: Balloons fall from the ceiling following U.S. President George W. Bush’s speech accepting his party’s nomination on the final night of the Republican National Convention September 2, 2004 at Madison Square Garden in New York City. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Scrolling through social media or watching on TV, you can’t miss the pageantry accompanying the national political conventions. The bright lights of news media; the red, white and blue décor; the thunderous applause as the party leaders deliver rousing speeches. But the vivid spectacle is temporary. The signs, hats, buttons, balloons and commemorative bobble-head toys tend to disappear when the convention ends, the decorations taken down and confetti swept up as the election year grinds forward. But for curators at the National Museum of American History, these objects, collected from the Republican and Democratic National Conventions are invaluable for research and possible exhibition.

Rebecca Seel spoke with Lisa Kathleen Graddy and Jon Grinspan, curators with the Division of Political History, before they left for Cleveland to attend the RNC, to find out how they decide what political items to collect and why they might be significant.

As political history curators attending both of the 2016 conventions, can you tell us what you’ll be doing there?

Lisa Kathleen Graddy: We’ll be observing and documenting the event. We’ll also be talking to the delegates on the floor to see how they’re experiencing the event and to acquire materials that they have that are representative of their experience there. So it’s the things they wear, the things that they make, and the things that they’re trading around and acquiring during the convention.

Hats worn by campaign delegates to previous political conventions from the collections of the Political History Division of the National Museum of American History.

Are there things that you’re keeping a lookout for when you head to the convention floor?

Jon Grinspan: To me, I think there are two categories. First, there are things that we’ve collected before that we want to show continuity (the hats, the standards), and we want to get the 2016 version too. Second, there’s stuff we hope that will say “2016” in particular in 50 years, and kind of capture and encapsulate this moment.

Delegates on the floor of the 2008 Republican convention at the XCel Energy Center in St. Paul, Minn. The vertical signs held by delegates representing each state are known as standards.

We don’t go out looking for particular objects but there are categories we know will be important. Hillary as the first female presidential candidate, immigration is a big issue this year, there are topics we know we want to find something related to.

LKG: On some level, two things are going on [on the convention floor]. There are things that are put out by the convention, so these are the things that express the RNC’s viewpoint, or the DNC’s viewpoint, or express the candidate’s viewpoint, not a great word here but the “establishment’s” viewpoint. Then there’s the material of the delegates, often made by individuals, that can be very personal. Homemade items might be perfectly in concert with the official material or might be diametrically opposed to opinions being highlighted by the RNC or DNC, so that’s always interesting. In a way, it’s like watching an argument or a conversation through things, not necessarily through spoken voice.

Buttons featuring Republican candidates for the 2008 presidential election from the collections of the Political history Division of the American History Museum.

One of the things that’s going to make this election significant is this will be the first time a woman is running as the candidate for a major party. So what we collect won’t just represent this campaign year, it will represent the journey that women have made through the political process. So we’ll be looking for that as well.

One moment in that journey already represented in our collection is the story of woman suffrage pickets. When Woodrow Wilson wouldn’t speak to them anymore, they took their conversation on cloth to his front door. You could watch the conversation go back and forth between statements on their banners. In a way, it’s the same thing with objects we collect from the conventions. You can watch signs and things that people are wearing and making and sort of have a conversation about issues and candidates.

JG: And part of what we’re looking for will be protests, of course. We’re going to be inside collecting in the convention, it’s the priority, but there’s a conversation going on outside that perimeter that we’re interested in as well.

A woman suffragist pickets outside the White House. The suffragists used President Woodrow Wilson’s own words against him and stayed on duty in all weather and in the face of taunts, threats and physical violence.

There is a fabulous cheesehead hat from the 1996 DNC that’s quite an interesting object in the collection. Did you have a wishlist for anything as unique as that?

LKG: Anything that really strikes the eye, strikes the heart, is interesting. One of the things we have is a Dole pineapple hat—it’s literally a papier-mâché pineapple but it says “Ohio” because it was from the Ohio delegation at the Republican convention for Dole. That’s just wonderful on a bunch of levels because people look at it and say, “I don’t understand why it’s an Ohio pineapple.” And then you can kind of watch the delayed reaction: “Dole!” So things that are humorous, things that are intriguing, things that are just plain interesting-looking.

Patricia Hawley decorated and wore this hat while serving as a Wisconsin delegate to the 1996 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

So what is a curator’s “ask?” When you go up to talk to someone at conventions, how do you start that conversation? You’re asking them to give you something they possess, how does that work?

LKG: We usually start by saying, I really the ‘blank’ you are wearing, that is so cool, can you tell me about that?” because a) you’re really interested and b) people love to talk about the things that they have and that they’ve made, and then you work your way around to explaining why it would be a wonderful thing to have in the Smithsonian Institution. Would they be willing to part with it and make it a part of the national collection? And if they’re not ready right now, we would be happy to hear from them later. That is why we carry a large supply of cards.

Why is it important to collect political history items as events are happening instead of just waiting until “the dust clears” and the election is over?

LKG: A lot of it will go away.

JG: Exactly.

LKG: Things that will be at the convention, they will clean it up on Friday night. If we don’t take it now, it won’t exist except in photographs. So the material that really shows what was happening on that floor, when you have those photographs that show massive arenas and signs and responses to what’s going on on the stage, this is how you know history is real. Tangible objects, real things, let you know that something happened and that people held them, and used them, and they made them, and they make all those pictures and all those words real.

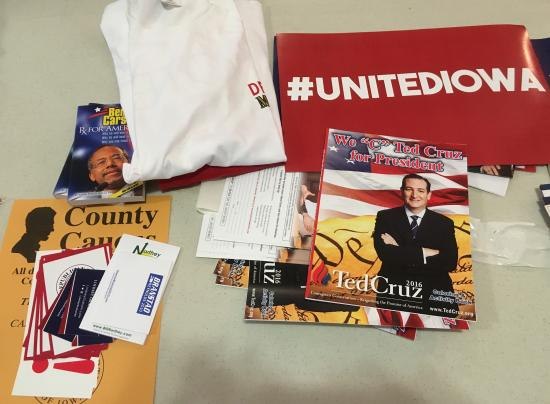

A few of the objects American History curators have collected from Republican candidates and supporters in Iowa during the 2016 caucus.

JG: And a lot of the truly valuable stuff historically doesn’t seem valuable at the time so it ends up in a dumpster because no one sees the way an object can encapsulate a moment and hold onto history. When you walk through the museum, half the stuff you see that is really powerful in exhibitions is not Abraham Lincoln’s hat, is not the Star-Spangled Banner, as powerful as those things are. A lot of things aren’t self-evidently powerful at first, so people don’t realize what they’re holding or what they’re wearing.

JG: Going to the [Iowa] caucus and feeling the night of the caucus, how uplifting it was to watch ordinary Americans, in a high school cafeteria, vote and choose, debate and get along, a lot of people will remember this as a hostile election in many ways but that sense of going and…these are your neighbors talking to each other and being civil and orderly and choosing, and even if they disagree…there was a really uplifting sense there.

During the caucus and the primary we visited a lot of campaign headquarters in the process of closing down in the last few hours but all the objects that represented that history were still there, so the proof that this history existed, it could be documented—it’s kind of to me what we’re doing. These moments are going to pass, they’re going to be in the rear-view mirror, but we can maintain collections and have a sense of what happened.

LKG: “Elizabeth Dole ran for president? Really?” Yeah, here are the buttons! It’s one of the reasons we go out early, to get the field while it’s still large, before it winnows down to just these two candidates.

These signs are from the New Hampshire Rebellion’s “We the People” convention, which took place Feb. 5 – 7, 2016 in Manchester, N.H. It’s goal was to “fight big money in politics,” according to the event’s website.

Lisa Kathleen, you’ve been with the Division of Political History for elections previous to this, so what do you think is different now versus what was collected in the past. How has the ecosystem of political material changed?

LKG: In some ways it’s more the same than I think people want to believe. There are still signs, buttons, all the odd gimmicks and advertising things that promote your candidate, to show your allegiance to an idea or a person or cause. Those are still very real. They are the way that we proclaim our values, our beliefs, and literally our allegiances, and we wear them for others to see, we hold them for others to see.

A poster at the campaign headquarters of Hillary Clinton in Manchester, New Hampshire, urged supporters to connect with the campaign on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

LKG: Now there’s a whole new world of social media put on top of that and that’s an interesting new addition, but it hasn’t made the core of campaign communication go away; people are still looking for those buttons and looking for those bumper stickers and they certainly put yard signs everywhere. A lot of it is augmentation.

If the Smithsonian built a time machine, which election would you want to go back to and collect from and what intrigues you about that particular election?

LKG: You want to see that first William Henry Harrison stuff. I want to see the people suddenly go “you can buy stuff!” because ribbons and things have always existed, but when they really started producing STUFF and you could really trick yourself out as a supporter, it would be interesting to see what people made of that the first time, obviously they took to it, but what that felt like.

William Henry Harrison was considered the first symbol-created candidate. In the 1840 election, he used log cabins, which his team built across the country as campaign headquarters, to represent his populism and “man of the people” appeal.

JG: 1896 was the year when this kind of outsider guy, William Jennings Bryan, gets the nomination for the Democratic Party and this big insurgent movement and some Democrats love him and some people say, “Who did we just nominate? Who is this outsider representing this insurgent movement?” In 2016, I think it would be interesting to go back to then and see what it is like, what are the similarities, what are the differences when you get the sense that a party is at a crossroads.

The 1896 campaign’s big issue was gold and silver standard. This “gold bug” pin in our collection showed the wearer was pro-gold standard.

Jon Grinspan and Lisa Kathleen Graddy will be at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland July 18–21 and the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia July 25–28.

Rebecca Seel is in the New Media Department and Office of Communications at the National Museum of American History. She is an avid C-SPAN viewer. A version of this posrt was originally published by the American History Museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 21 July 2016

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture