Gotta visit ‘em all!

The Smithsonian is home to the rare and unusual, the awe-inspiring and beautiful, and collections that can be found nowhere else on Earth. But who knew we’re also the go-to destination for pocket-monster collectors?

Add your favorite captures to our collection by sending a screenshot to Torch@si.edu.

A female Nidoran in front of the Castle. This species of Pokémon is especially common around the National Mall. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

We’re used to seeing visitors on their phones around the Smithsonian museums. Whether they’re texting members of their tour group, Instagramming their favorite artifacts on social media, or using one of the Institution’s several apps, there’s no shortage to clicking and snapping and sharing going on within these hallowed walls.

But what about monster catching?

The latest craze sweeping the globe has arrived, and it turns out museums across the country, including the Smithsonian’s, are crawling with Pokémon. The little “pocket monsters,” who have been dwelling in Gameboys, televisions and trading cards since the 1990s, have suddenly spilled into daily life with the release of the smartphone app Pokémon Go.

Developed by Niantic, Pokémon Go is a free-to-play location-based augmented reality mobile game that allows players to capture, battle and train virtual creatures, who appear on device screens as though in the real world. Released just this month, the game has quickly became one of the most used smart device apps.

The game overlays the Pokémon world onto real life—like Google Maps, but with stray animals everywhere. But these little critters won’t come to you. Players have to get off the couches and into the real world, bushwhacking and beating the tarmac to find Pokémon to add to their collection. Once a Pokémon is pinpointed on the map, the game enters an augmented reality mode. The wild Pokémon is there in front of you, its animated form superimposed on your phone camera’s view of the street corner, the National Mall or your favorite museum. Once spotted, the Pokémon is yours to photograph, catch, keep and treasure forever. Or at least until the game drains your cell phone battery.

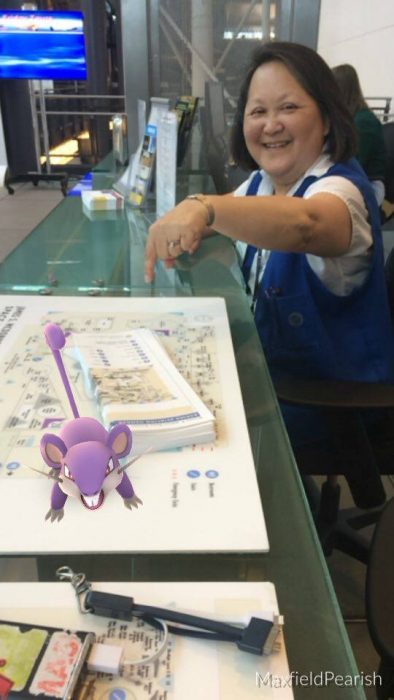

Information desk volunteer Beverly Knox and her Rattata Pokemon at the Udvar-Hazy Center. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

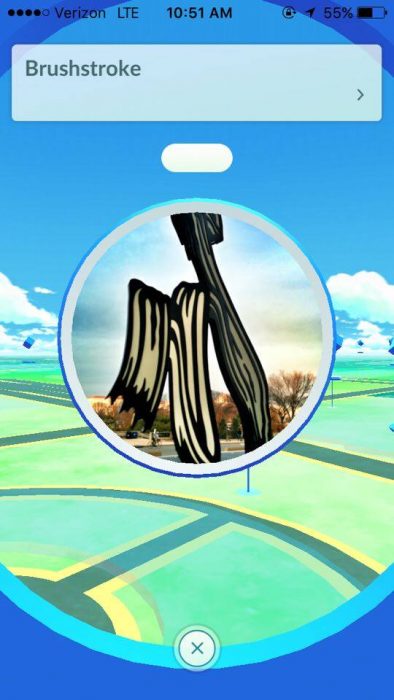

Special locations in the game correspond to real-life locations, usually monuments, national landmarks or just some place cool. Which brings us, of course, to the Smithsonian. For example, below is a view of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden’s distinctive ring architecture from the game.

The floating blue icons represent PokeStops, locations where players can meet and gather new supplies for their Pokémon hunt. Draw closer and you see that Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstroke sculpture in front of the Hirshhorn is a PokeStop.

Roy Lichtenstein’s “Brushstrokes” is a PokeStop in the auigmented reality game Pokemon Go. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

If you visit the Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center, you might discover (if you’re a Pokémon trainer, that is) that the Space Shuttle Discovery is more than a spaceship—it’s also a Pokémon gym, where players can pit their Pokémon against each other for in-game money and glory. (No actual Pokémon were harmed in the making of this game.)

Although Pokemon trainer Fernando Diaz Jr. dominates the Space Shuttle Discovery Gym, he will not be quitting his day job as a lieutenant with the Office of Protection Services to train Pokemon full time. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

Players have been crowding the the sidewalks and museums around the Mall in record numbers to “Catch ‘Em All” despite the summer heat. Among the Smithsonian Castle, the Enid A. Haupt Garden, the Freer and Sackler Galleries, the African Art Museum and the Ripley Center alone, there are 22 PokeStops, making the Smithsonian a hotspot for Poke-activity. Smithsonian Gardens volunteer and interpreter Sandra Blake doesn’t play the game herself, but she’s seen quite a few people staring at their phones. “And while they’re here anyway [looking for Pokémon],” she says, “I get to tell them all about our gardens. The flowers are coming in beautifully right now, especially the yellow ones!”

Volunteer Sandra Blake poses with a Poliwag, caught enjoying the Enid A. Haupt Garden. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

While not all museums and historical sites are appropriate for Pokémon hunts (the Holocaust Museum and Arlington Cemetery, in particular, have asked players to be respectful by not playing there), the Smithsonian welcomes visitors to come on in and have a little fun. Playing Pokémon Go can encourage players to rediscover their community, meet others with similar interests, get some Vitamin D and a maybe a dose of culture, all at the same time!

Find any cool Pokémon around the Smithsonian? Give us a shout at torch@si.edu with the when and where and send us a screenshot. We want to catch e’m all, too!

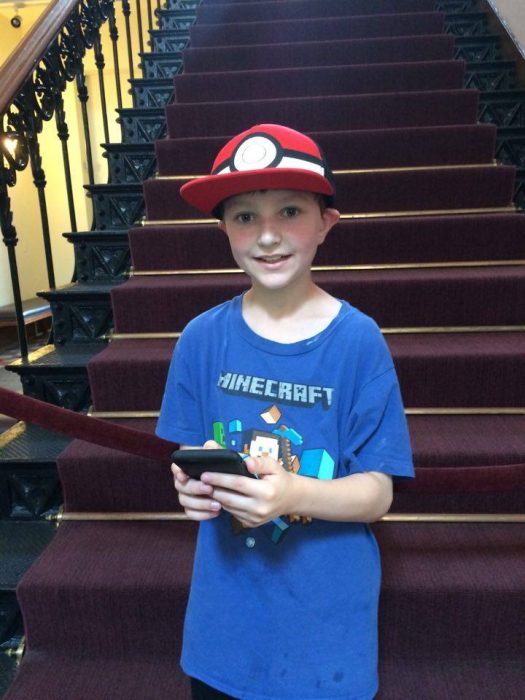

A young visitor from Nebraska dons an appropriate cap while catching Pokemon at the Smithsonian Castle. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

___________________________

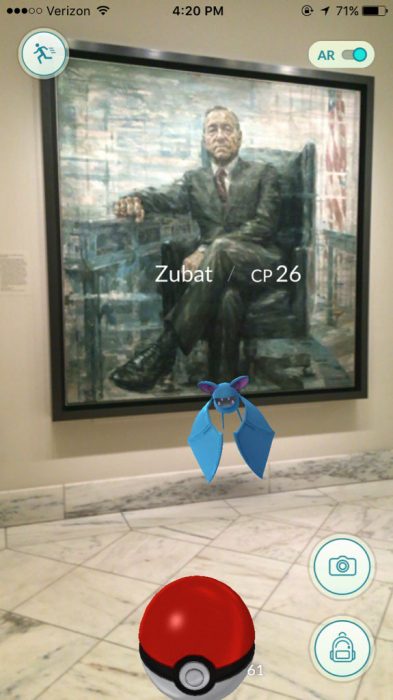

A Zubat hovers in front of the portrait of Frank Underwood from “House of Cards” at the National Portrait Gallery. (This is all too meta–a fictional character in a real gallery featuring a real portrait of a fictional president.) (Photo via NPG Twitter)

_________________________

Visitor Experience Manager Samantha Berry at the Natural History Museum, captured a mammoth-sized Raticate. He belongs in the collections! (Photo by Samantha Barry)

_______________________

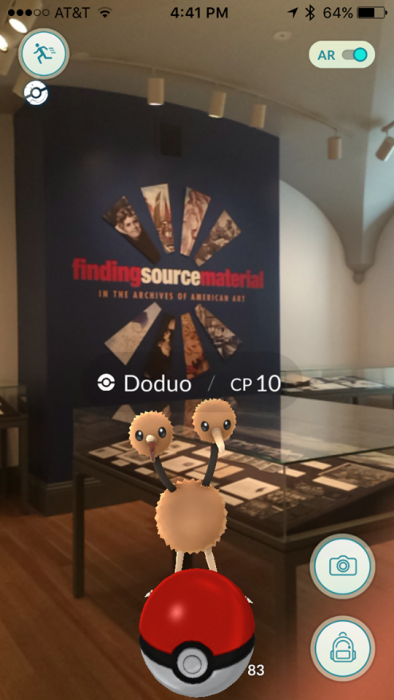

A doduo looking for source material was instead found by a trainer at the Archives of American Art. (Photo via AAA’s Facebook page.)

__________________________

Pokemon Squirtle demonstrates his good taste with a visit to “Thom Brown Selects” at the Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York. (Photo via Cooper Hewitt Twitter)

______________________

Geodude seems right at home hovering across the National Mall from the Natural History Museum. (Photo by Max Kibblewhite)

_______________________

Posted: 18 July 2016

- Categories:

A Pokémaster before his time, Spencer Fullerton Baird, named first Curator of the National Museum at the Smithsonian in 1850, carried out Secretary Joseph Henry’s policy of gathering only materials not previously collected by others. Baird proposed concentrating on collections illustrating the natural history of North America and created a system of exchange, trading duplicate specimens for unique specimens. He proposed to furnish travelers with the means of “determining the character of objects collected in various part of North America,” thus creating an expansive network of collectors (Pokémasters), and the forerunner of the Pokédex. Fittingly, the National Museum’s building, now known as Arts and Industries, hosts 2 Poké Stops.