#InclusionWorks: How do you collect a stare?

Katherine Ott is the curator of Science and Medicine at the American History Museum. She researches and oversees collections that attest to our changing perceptions of wellness, illness and bodily difference. For part two of our series highlighting Disability Employment Awareness Month, Max Kibblewhite spent some time with Ott to learn more about how notions of disability are reflected in our collections.

A hand-knit lap blanket featuring the symbol for universal access. From the collections of the National Museum of American History.

How would you describe the scope of your work at the American History Museum?

I think of what I do as history of the body and bodily differences. That includes intersectional topics like disability, race, sexuality, infectious disease—all the things that mark us as different or unique. The subject of disability itself is so broad I could devote all my time and attention to it alone, but curators don’t have the luxury of focusing on just one topic.

I do pan-disability work. I think a lot about objects and disability in museums because I work in a museum, of course. I’ve written about the material culture of disability and technology, as well as the history of technology as it relates to disability.

Disability is probably the aspect of experience that is least included when it comes to the Smithsonian’s collection. We talk about race, class and gender, but disability never makes it into the conversation. No one really objects when disability is the punchline to a joke because ableism, unlike racism or sexism, is an ism that is yet to be unpacked. Ableism is an assumption that everyone experiences the world the same way and if you are different or need accommodations there’s something wrong with you personally rather than something wrong with the design or the environment. Ableism is everywhere.

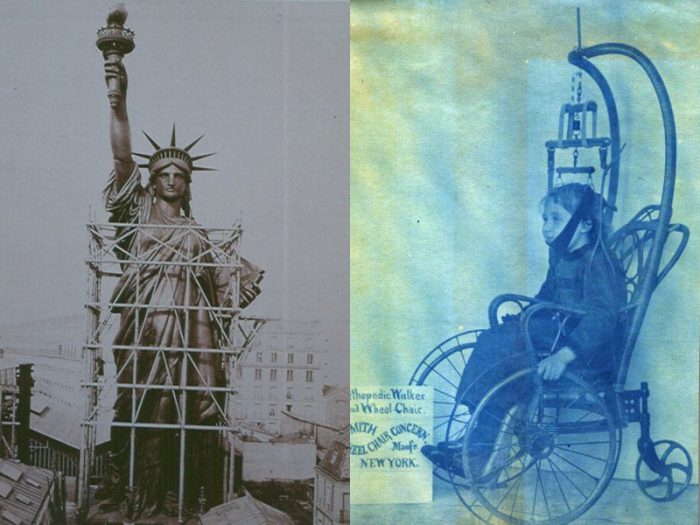

Ideas related to disability are often just beneath the surface, On the left, the Statue of Liberty wears a body brace, the supporting scaffolds used to support it as it was built. The young girl in a wheelchair with suspension support for her head and shoulders is a living version of the Statue of Liberty under construction.

Do we have a “disability collection?” How large is it?

It depends on how you categorize it. In one way, everything related to the history of medicine, at least in my division, is directly related to disability because that’s the medical model—that every difference needs to be “fixed.” In another way, everything in the museum is designed with someone in mind, so everything we have relates to disability in some way, or can be interpreted that way. There’s the really interesting field of disability aesthetics that looks at how you can pull disability out of the design of practically anything. Take the Venus Di Milo, for example. She’s a Greek statue, she’s classically beautiful, and she has no arms. Is that not disability? It’s familiar and all around us, but we don’t usually pull out the disability aspects of it.

Aphrodite of Milos, better known as the Venus de Milo, is an ancient Greek statue and one of the most famous works of ancient Greek sculpture. Created sometime between 130 and 100 BCE, it is believed to depict Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty.

How do you collect for or from the disability community?

It’s very strategic. I work directly with communities for contemporary collecting to understand what’s important to the community itself and how it relates to what we already have. Does the object come with a good story, is it in good shape? Is it going to last, do we have the space for it? For example, we don’t need another iron lung, even though they are fascinating objects and there are design and technology differences between them, because we already have three in the collection. There are usual design questions when you collect that you ask yourself and you ask of the object.

We have things from well-known people as well as everyday things. I work with ADAPT, a disability rights group that’s been going for a long time, the American Foundation for the Blind, independent living centers, the Society for Disability Studies, and a dozen more. I don’t live it, so I rely on these groups and others for guidance all the time. I rely on those who live the embodied experience to help understand it. There’s a lot I don’t know.

Can an object be disabled?

I think everything can be shown to relate to disability history because, when we talk historically about what a typical person might have been like, there’s no one answer. The historic record tends to tell the stories people who have more money or prestige. Everything we create is designed to be used by people with particular body types or phenotypes. Think about eyeglasses, for example. Our website, Everybody, explains how the concept of 20/20 vision as the ideal—being able to read the 20th line of an eye chart at 20 feet—is completely arbitrary. Someone who never traveled faster than a horse drawn-cart had no need for the long-distance vision a truck driver on the highway needs. An illiterate person who never needed to read had no use for reading glasses. These are disability stories. Millions of people wear glasses today, but they don’t think they have a disability.

People sensitive to light wore tinted lenses. These examples illustrate popular 19th-century designs such as the pince-nez that clasped the bridge of the nose and ones with hinges so that a clear lens was available behind the tinted one.

Do you have a favorite object from the collection?

I don’t play favorites because I’m fickle and whatever is in front of me is my favorite at the moment because everything is so great!

There are several objects that are really good attitude adjusters, or that are really surprising to visitors. I love the “Do It Yourself Curb Cut” acquired from a couple of activists in Denver in 1980. People had been falling out of their wheelchairs and breaking bones trying to get over street curbs and the city wasn’t complying with the law and creating mini-ramps at street corners. The activists finally took sledgehammers and made their own curb cut. The object may just be a chunk of concrete but the story behind it is really amazing. I guess I like best the things people have created themselves. We have keys that were made by psychiatric inmates that are all highly individualized. We don’t know why or by whom they were made but they are very intense artifacts. I like the creative ways people replace worn-out cane tips. I like the braille writers. I like the things that tell the story of a person with a disability.

What is your goal as a collector and curator?

There are things I want to be able to include in the collection but I probably won’t ever be able to. There are aspects of disability that are intangible and can only be collected indirectly. For example, how do you collect a stare? Staring is a huge issue in the life of a person who is different. You are stared at. It excludes you. It may make you want to never leave the house. It marks you, it stigmatizes you. How do you capture that? How do you capture the pain it causes and how it screws around with someone’s psyche?

How do you collect microagressions? These subtle slights and slurs can be so fleeting and so easily denied by those who are not affected by them, but it doesn’t matter—if it hurts you, it hurts you. When people talk to a standing companion rather than the person seated in a wheelchair. Or a child is made to sit still and not rock back and forth, or when conference speakers are expected to use the podium but its height is not adjustable. Or there are no captions on the video. How do you document and collect the ways these indignities differ in different eras and different locations?

Eugenics is another topic that’s hard to collect and to give substance to. I have a couple of objects from which we can infer assumptions about who has a life worth living. I can skirt around it — I can present evidence on sterilization, on selective abortion, on institutionalization, but these things are hard to collect and difficult to interpret. As with the example of keys created by the psychiatric inmates, we have the object, but how do we tell the story? There would be a range of interpretation from the inmate, the doctors, the people in the community, the family members who have differing opinions. There are so many interpretative voices.

There’s a really important saying in disability studies that’s Nothing About Us Without Us. I think that’s good for anything we do that you don’t pontificate, that we share power and include people.

“I can’t even get to the back of the bus”; ADAPT activists protesting for accessible transportation, Philadelphia, 1990

Read part one in this series: #InclusionWorks: National Disability Employment Awareness Month

National Disability Employment Awareness Month is a national campaign that raises awareness about disability employment issues and celebrates the many and varied contributions of America’s workers with disabilities. The theme for 2016 is #InclusionWorks.

NDEAM’s roots go back to 1945, when Congress enacted a law declaring the first week in October each year “National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week.” In 1962, the word “physically” was removed to acknowledge the employment needs and contributions of individuals with all types of disabilities. In 1988, Congress expanded the week to a month and changed the name to “National Disability Employment Awareness Month.”

Posted: 10 October 2016