#InclusionWorks: Let’s be reasonable

For part three of our series, #InclusionWorks, Max Kibblewhite spoke with Carol Gover, the Affirmative Employment Manager in the Office of Equal Employment and Minority Affairs. OEEMA oversees the implementation of employment nondiscrimination laws and works with staff throughout the Smithsonian to ensure that employment decisions are not made based on illegal considerations of race, color, sex, gender, nation of origin, disability or other discriminatory consideration. As part of this commitment, the Smithsonian provides reasonable accommodations for the known physical and mental limitations of qualified individuals with disabilities to allow them to perform the essential functions of their job.

One of your responsibilities is Reasonable Accommodations Manager. What does that mean?

Gover: Reasonable accommodations are modifications to the workplace that assist someone in being able to perform the essential duties of their job. I work with supervisors and employees to make sure employees receive accommodations that are reasonable, effective, and do not cause undue hardship.

Can you give us some examples of best practices or reasonable accommodations?

We work with a lot of different cases. Many accommodations are very simple; for example, supervisors can make schedule adjustments. Many times, computer systems and programs have accommodations built in that employees and supervisors aren’t aware of—simply making adjustments to the system or the program can make someone’s life a lot easier. Some employees might need a sign language interpreter. Sometimes it’s a change in the office setup that helps an individual to work more effectively.

Have you seen changes in how we are able to accommodate employees over the years?

Assistive technology can be a reasonable workplace accommodation. This BIGtrack Trackball large trackball that requires less fine motor control than a computer mouse or trackball. (Image via BIGtrack)

What’s fascinating to me is that many “accommodations” are just simple common sense—the things that might have caused a manager heartburn 20 years ago are commonplace business practices in 2016. This includes such things as ergonomic moussing devices and the ability to adjust font-sizes. Newer technology like smartphones incorporated accessibility options like these in their early designs. It’s just common sense to create flexibility for users.

How does one go about getting a workplace accommodation?

Let’s start with the employee. Generally, employees can just talk to their supervisors or they can contact us directly to explain what they need. Some individuals get advice from medical practitioners and occupational services or employee assistance programs. There are a lot of avenues for people to indicate that an accommodation may be needed. A lot of the requests come through me to help facilitate the process. Sometimes, accommodations are simple and occur without any kind of formal process. For example, an individual might need a chair that can be raised or lowered and a supervisor just replaces the chair. Accommodations happen all of the time, but if supervisors need guidance they contact me so we can determine what accommodations are possible. In some cases, we may need to collect medical information, which is then sent to Occupational Health Services. We have an excellent team here at the Smithsonian, including colleagues in the Office of Human Resources and the Office of General Counsel, that discusses issues as they arise and works toward resolution, while maintaining the confidentiality that employees deserve. If an applicant for employment requires accommodation, it can be requested through the Human Resources specialist or the person setting up the interview. We also partner with Beth Ziebarth, director of the Accessibility Program and program specialist Ashley Grady in the Accessibly Program when there is overlap between staff and visitor accessibility.

There must be many challenges in managing accommodations for the large and diverse workforce we have at the Smithsonian.

One of the challenges is not only the diversity and size of the museums and offices, but the many different types of jobs that we have. When we’re making accommodations we’re looking at the individual’s needs as they apply to the job being performed. Some jobs at the Smithsonian are very physical. Some require travel. Others require set schedules. Other jobs must be performed on site. These are the kinds of challenges supervisors and employees have to discuss during an interactive process to make sure we find accommodations that are effective for the employee’s needs and reasonable for the employer. There are times that the accommodation that an employee requests is not reasonable but we can usually find another accommodation that is effective. For example, an employee may request an amplifier for the phone, but a headset with adjustable volume may be more effective.

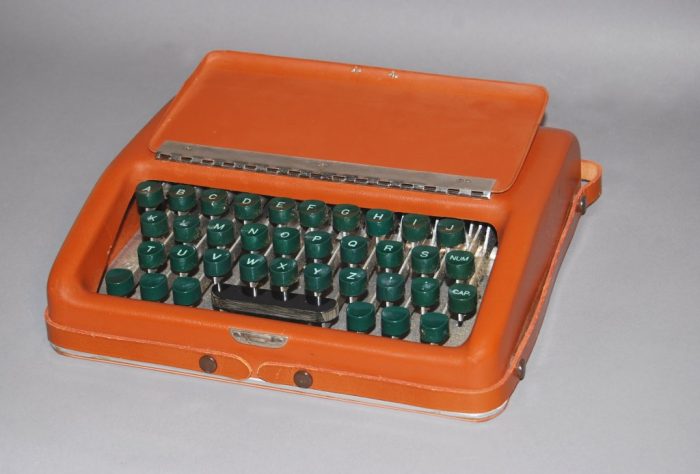

This small mechanical keyboard from the 1950s has a Braille cell on the back and was used to communicate with a person who was deaf and blind. Finding information, purchasing goods, requesting services, getting from place to place—all entail devices, tools, and technology. New forms of technology that benefited mainstream society often initially excluded people with disabilities because of inadequate design or planning. (National Museum of American History)

Our goal should be to increase knowledge and understanding of what accommodations entail and encourage employees and applicants to ask for what they need, so that, even if we cannot provide a specific accommodation, we can work together to find an effective alternative.

The Smithsonian has dedicated people working together on accommodations issues. The fact we can reach out and get assistance from one another makes it much easier to facilitate accommodations discussions. I’m proud to be here.

For more information on rights and responsibilities, please contact the Office of Equal Employment and Minority Affairs or go to http://prism2.si.edu/SIOrganization/OEEMA/Pages/RABFEAIA.aspx.

Read part one in this series: #InclusionWorks: National Disability Employment Awareness Month

Read part two in this series: #Inclusion Works: How do you collect a stare?

Held each October, National Disability Employment Awareness Month is a national campaign that raises awareness about disability employment issues and celebrates the many and varied contributions of America’s workers with disabilities. The theme for 2016 is “#InclusionWorks”

NDEAM’s roots go back to 1945, when Congress enacted a law declaring the first week in October each year “National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week.” In 1962, the word “physically” was removed to acknowledge the employment needs and contributions of individuals with all types of disabilities. In 1988, Congress expanded the week to a month and changed the name to “National Disability Employment Awareness Month.” Upon its establishment in 2001, ODEP assumed responsibility for NDEAM and has worked to expand its reach and scope ever since.

Posted: 17 October 2016

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , News & Announcements