#InclusionWorks: Sharing the Smithsonian with every visitor

For part four of our #InclusionWorks series, Max Kibblewhite chatted with Beth Ziebarth, director of the Smithsonian Accessibility Office and program specialist Ashley Grady. The Accessibility Program works across the Smithsonian to insure that all visitors have access to our buildings, programs and exhibitions. The Accessibility Program frequently coordinates with the Smithsonian’s Office of Equal Employment and Minority Affairs, but generally, OEEMA works with staff, AP with visitors.

Ashley Grady works in both worlds as coordinator of internship programs for people with disabilities. Project SEARCH is a 10-month internship program for young adults with cognitive or intellectual disabilities. Access to Opportunities is an internship program for college students with any disability. Programs like these work with OEEMA to ensure that reasonable accommodations are made for all participants.

Torch: How do you make sure our museums are accessible to all visitors? Are there best practices?

Beth: The Accessibility Program works on everything from policies to practices and procedures. Our policy is Smithsonian Directive 215, which covers accessibility for people with disabilities, including visitors, staff, interns, volunteers, fellows—anyone associated with the Smithsonian. Practices and guidelines are then needed to implement those policies. Procedures include such things as the use of service animals. That’s the policies, practices and procedures side, but we also work on facility design, exhibition design and programming we manage in concert with other units and museums.

We do a significant amount of training for Smithsonian staff on accessibility and disability topics. This can include everything from training new security officers who will interact with visitors with disabilities at the entrance to our museums or working with exhibition designers on how to introduce effective tactile elements and technology to a new exhibition. We work with the disability community through groups such as the American Association of People with Disabilities, with other cultural arts institutions, such as the Kennedy Center, and with organizations such as the HSC Foundation (a parent organization that supports different levels and stages of care for people with disabilities) to identify opportunities to better serve the community.

Ashley: This is an example of one of the things our office might do: If a visitor were to call and say, “I have a vision impairment and would like to set up a tour of the Air and Space Museum,” our office would coordinate with the museum(s) to make those arrangements so that the visitor can have the most meaningful experiment possible. If a visitor needs an ASL interpreter for a public program, we can coordinate that, as well.

Beth: We also provide technical assistance for staff on questions related to accessibility, whether it’s how wide a doorway should be to meet federal accessibility standards or how we can be sure we’re providing effective communication for someone who is deaf.

Accessibility is an integral part of the David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins at the Natural History Museum, designed by Reich+Petch Design. (Photo courtesy RPDI)

The Smithsonian is very big and parts of it are very old. What kind of challenges do you face in making SI accessible and how do you work around them?

Beth: It’s a constant balancing act—lots of spinning plates! Truthfully, for museums, the facilities side of accessibility is not rocket science. We really don’t have to think of new solutions to an issue because there are federal standards that address such things as ramps and doorways. Facilities issues are relatively simple, even for older buildings. For example, the National Museum of Natural History was built in 1910 and its south entrance is a wide flight of marble steps. We are currently working on the design of two symmetrical sloped walkways on either side of the stairs so we will finally have an accessible entrance to the museum on that side, while still preserving its architectural integrity. It’s been a project that we’ve talked about for many, many years and things have aligned so it’s finally moving forward.

Providing visitor accessibility becomes a little more challenging when it comes to programming, which includes everything from exhibitions to public programs, to the IMAX theaters to museum shops and cafeterias. Our office has written guidelines on how to make an exhibition more accessible. We have guidance on how to make a public program more accessible. We know how to make a shop accessible. It’s all about thinking how to meet the needs of a wide range of people.

A wheelchair lift was installed in the Children’s Room at the South Entrance to the Smithsonian Castle to allow accessible access to the Great Hall. (Photo by Paul Westerberg)

Sounds like a big job. How do you accomplish it?

Beth: We are a small office of two, soon to be three. We have a fellow who’s currently working with us as well as several interns and volunteers. Truthfully, the only way our tiny office can be effective is because the entire Smithsonian, by policy, is working on accessibility. Everyone has a responsibility to enhance inclusion and accessibility—whether for visitors or staff. And just as importantly, everyone should recognize how easy it is to thoughtlessly sabotage accessibility. For example, a restroom has been carefully designed to be accessible, including the location of a wastebasket. If the wastebasket is emptied and then carelessly replaced near the door, it might block the clearance someone in a wheelchair needs to enter or exit the restroom.

So, we all have a responsibility: Security officers can be welcoming to a visitor entering a museum or inadvertently embarrass someone because of what they say or do. A museum shop clerk can offer to get something that’s out of reach. An exhibition designer can be thoughtful about how to integrate captioning and verbal description into a video. Everyone at the Smithsonian has a role to play. We’re here to be cheerleaders but we rely on the rest of the staff to help carry the load.

Ashley: Part of it too is trying to encourage people to think that accessibility is not necessarily something extra that needs to be added—it should just be something that’s a part of universal design. Helping people to get more into that mindset is one of our goals.

Beth: We don’t have specific numbers of how many people with disabilities are coming to the Smithsonian museums. But, if you look at the population of the United States, of some sort. The chances are that the museums’ visitor population is reflective of that statistic. When you look at the world’s population as a whole, there is an even greater percentage of disabled people. Clearly, a lot of people with disabilities visit the Smithsonian and it is our obligation to provide an equal opportunity for people with disabilities to participate in our programs. It’s a matter of trying to establish the basic human right to cultural access. That’s our motivator. Everyone should be able to participate in what the Smithsonian has to offer.

Ashley: I think this is where our office and OEEMA have such a good collaborative working relationship. The goal of Project SEARCH, for example, is to help diversify our workforce and provide opportunities for individuals who want to work and gain the job skills that can allow them to take their place in a diverse workforce. Project Search is an international program with more than 400 sites throughout the world. The Smithsonian was one of the first organizations to have a Project SEARCH program designed specifically to provide inclusion and access to internships and careers in the cultural arts.

We have really had an excellent response in terms of changing the culture and challenging ideas about what individuals contribute to the workplace, whether they have disabilities or not. In the same way, we want all visitors, regardless of disability, to have access to our content and have a wonderful experience of the Smithsonian. Through Project SEARCH and Access Opportunities, our office gets to promote accessibility, not only on the visitor services and front-facing side, but also behind the scenes, as well.

Beth: It’s been shown over and over again in the museum field that visitors want to see their own stories reflected in exhibitions. It just doesn’t work to do it any other way. (Read more about how notions of disability are reflected in our collections and exhibitions. #InclusionWorks: How do you collect a stare? )

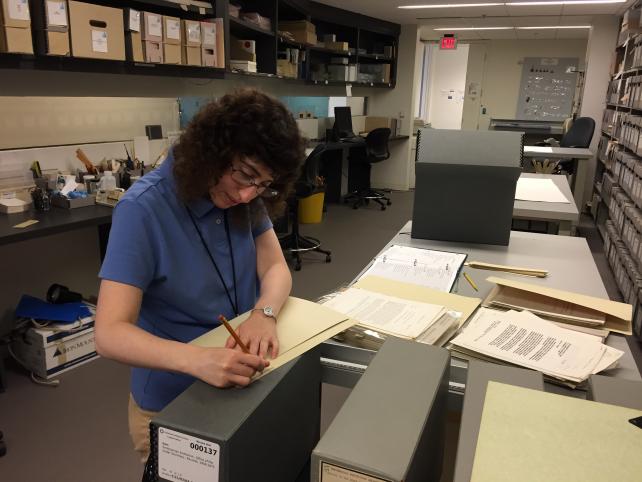

Heather Weiss was a 2015 Project SEARCH intern for Smithsonian Archives. She is seen here transcribing information to new archival folders. (Photo courtesy William Bennett)

Looking forward, what’s happening next?

Beth: On the programs side, we’re working more on multisensory experiences that can benefit everyone, regardless of disability. Someone who is blind no doubt will benefit from a three- dimensional or tactile element in an exhibition, but sighted people will be touching and interacting with that element, as well. Touching something creates a tactile connection that unites the auditory and visual and everything that’s going on in that exhibition space. We’re working on access for visitors who are blind or visually impaired, which is difficult, because historically, museums are very visual experiences (look, but don’t touch!) We’re also working on developing access for people with different types of cognitive disabilities.

Ashley: We’re thinking about new kinds of programming. We have greatly expanded Mornings at the Museum, a program originally offered for children with autism ages 6 to 12. (More about Mornings at the Museum is coming up in the final part of our #InclusionWorks series.) We would like to develop similar programs for teenagers and younger adults in their 20s and 30s. We’re interested in developing programs that can provide meaningful museum experiences for older individuals who may have memory loss or dementia or Alzheimer’s. We’re very focused on working with all the museums to try to come up with strategies for visitors who are blind and have low vision by training as docents in verbal description. We work with the volunteers and information desk staff so they have a wealth of information they can provide to visitors with disabilities.

Beth: One of the benefits of a centralized Accessibility Office is that we can look at the Smithsonian as a whole to make sure we are offering consistent accessibility for people with disabilities. If we see a real variation among the museums, that’s problematic. If a family with a child who has a sensory processing disorder comes to the Smithsonian, they want to know they can access all of the Smithsonian equally—the dinosaurs, the pandas, the planes, everything.

Ashley: We want every visitor visitors to feel welcome and we want everyone to have an equally meaningful experience.

Read part one in this series: #InclusionWorks: National Disability Employment Awareness Month

Read part two in this series: #InclusionWorks: How do you collect a stare?

Read part three in this series: #InclusionWorks: Let’s be reasonable

Held each October, National Disability Employment Awareness Month is a national campaign that raises awareness about disability employment issues and celebrates the many and varied contributions of America’s workers with disabilities. The theme for 2016 is “#InclusionWorks”

NDEAM’s roots go back to 1945, when Congress enacted a law declaring the first week in October each year “National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week.” In 1962, the word “physically” was removed to acknowledge the employment needs and contributions of individuals with all types of disabilities. In 1988, Congress expanded the week to a month and changed the name to “National Disability Employment Awareness Month.” Upon its establishment in 2001, ODEP assumed responsibility for NDEAM and has worked to expand its reach and scope ever since.

Posted: 25 October 2016

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories