Windows can be a real pane for birds

Birds face constant threats from predators, pesticides and loss of habitat, but few people realize that millions of birds are killed each year by flying into windows. Amy Rogers Nazarov takes a clear-eyed look at the Smithsonian’s efforts to be bird-friendly.

This imprint was left by a bird flying into a window. Up to a billion birds die in collisions with glass each year in the United States, according to the American Bird Conservancy. (Photo by David Francher via ABC)

It’s not uncommon to see a sparrow crash headlong into a windowpane or door at your home or workplace. If he’s one of the lucky ones, he’ll sit there stunned for a while, then hop away.

The estimated total of birds actually killed by flying into glass is startling. According to the American Bird Conservancy, roughly one billion birds strike glass each year, most fatally.

Bird strikes are personal to Sara Hallager, curator of birds at the National Zoo, who ticks off a few recent incidents involving a robin and a warbler around the Zoo campus downtown.

A decade ago, as they considered the features of the permanent bird migration exhibit (slated to open in 2021 in a 1928 building now under renovation), Zoo personnel were deeply concerned about the problem. “The last thing we want to be doing is having birds hit our windows, especially when we are opening a new exhibit all about bird migration,” Hallager says.

Exhibit designers at the National Zoo make sure that the use of etched glass and other bird-friendly measures does not obscure visitors’ view. (Photo courtesy Smithsonian’s National Zoo)

“Birds don’t see glass the way we do,” explains Hallager, who in May marked her 30th anniversary as a Zoo employee. “They tend to interpret reflections of trees as actual trees and attempt to land on the reflection.”

There’s good news, however. Not only are builders and others becoming increasingly aware of the bird-strike issue, but also research shows that “fritting” the glass—using decals to apply a subtle pattern of wavy or straight lines or pictures (such as leaves) to glass—is an effective means of reducing bird strikes, often dramatically.

The Zoo sought to measure the scope of the issue in 2008, with promising results. “We sent volunteers around in the mornings to pick up dead birds” outside Zoo buildings, Hallager says. After decals were applied and the volunteers resumed their morning checks, “the number of dead birds was almost zero.”

Everyone is learning together how best to deploy the bird-friendly measures. In the earliest days of fritting at the Zoo, “the stenciling was so thick people couldn’t see the animals” behind the glass well, Hallager says. The Zoo also experimented with the spacing between vertical lines applied to the glass; if lines were more than two inches apart, birds still perceived they could pass between them, often with deadly results.

Another inventory now underway—this time of windows across NZP—sought to tally both the large expanses of glass as well as the tiny panes that pose a threat to birds, which flock to the Zoo year-round for its expansive tree cover. Even a three-foot span of glass can be fatal to a flying bird.

By simply adhering owl stencils to the window, the occupant of this office at the National Zoo dramatically reduced the incidence of bird strikes. (Photo courtesy Office of Planning, Design and Construction)

“Birds are relatable,” says Jennifer Daniels, senior landscape architect at the Zoo’s Office of Planning and Strategic Initiatives. “A bird is often the first and only animal someone might see in a day.” But perils to birds—especially migrating ones—are legion, she says. Making glass safer for birds, increasing plant diversity, turning off office buildings’ lights at night and other steps can be taken to make their habitats healthier, both at the Zoo and in people’s homes and offices. “We can teach our 2.5 million visitors a year about how they can help reduce bird strikes,” Daniels notes. “These are important steps for saving species.”

The efforts of NZP and the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (housed under the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute) are inspiring others to act.

Little by little, bird-friendly glass is being installed Smithsonian-wide, says Debra Nauta-Rodriguez, deputy director of planning and program management at Smithsonian Facilities’ Office of Planning, Design and Construction. New buildings and labs at SCBI, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center all feature fritted or stenciled glass. The Air and Space Museum is also taking steps to make its glass bird-friendly through the specification of tinted and fritted glazing for its upcoming revitalization project.

This dot-patterned frit on the fifth-floor glazing at the National Museum of African American History and Culture allows birds to perceive the windows as obstacles and avoid flying into them. (Photo courtesy Office of Planning, Design and Construction)

Not all Smithsonian windows post a threat, Nauta-Rodriguez added. The windows at the Natural History Museum have many small panes separated by mullions, which pose less of a danger to birds. In addition, the outward slant of much of the glazing at the new Museum of African American History and Culture—as well as the Corona’s lattice design that overlays this glass—deters bird strikes. The topmost floor, however, which contains staff offices and features vertical glass windows, required bird-safe glass modifications such as fritting.

Smithsonian Facilities is working to gather best practices around using bird-friendly glass into a document all units can consult as they move forward in their own attempts to be safer for birds.

Taking these steps “is part of being good stewards of our buildings and of our environment,” says Nauta-Rodriguez. “I came to [my current position ] after spending several years at NZP, which really raised my awareness. “Anytime I’m looking at a new project, I find myself asking the question, ‘What about the birds?’”

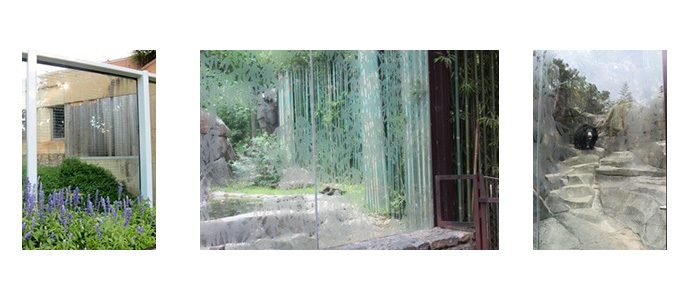

Examples of the use of bird-friendly glass at the National Zoo: From left, glass treatment at Think Tank (photo by Melba Brown) and at the sloth bear enclosure (photos by Tony Barthel)

Posted: 13 July 2017

Did you know that the eighth Smithsonian Secretary, S. Dillon Ripley, developed bird deterrent stencils for windows? He called the diving falcon silhoutte the “Shoo Bird.” He donated a supply of them to the Smithsonian’s museum shops to be sold to the public in 1974. See https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_1234 The Torch reported this in its June 1974 issue, which you can read here: https://siarchives.si.edu/sites/default/files/pdfs/torch/Torch%201974/SIA_000371_1974_06.pdf.

What a great bit of history! Thanks, Pam! (Pamela Henson is the Supervisory Historian for the Smithsonian Institution Archives.)