Profile in Perseverance: Ching-hsien Wang

The groundwork for Ching-hsien Wang’s career increasing and diffusing knowledge at the Smithsonian was laid long ago in China, where she grew up in a family of professors–and where her schooling was interrupted in third grade by the Cultural Revolution.

Ching-hsien Wang at a recent panel discussion hosted by Secretary David Skorton discussing what it means to be an American. (Photo by John Gibbons)

In 1988, when Ching-hsien Wang’s office was located in the basement of the Museum of Natural History, she mounted a large chalkboard on the wall to help her organize her thoughts and visualize her work.

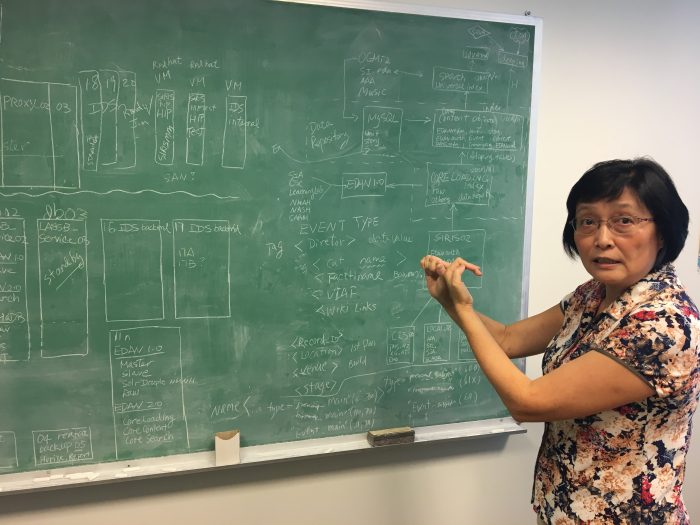

“I don’t like whiteboards,” says Wang, who will mark her 30th anniversary at the Smithsonian next year. She gestures at the very same chalkboard that’s followed her for nearly three decades, now on the wall in her Capital Gallery office and covered with a complex diagram of servers. Colleagues who at first chuckle at the chalkboard’s low-tech factor soon “come in and study it. It really helps me communicate with my team.”

Wang’s digital domain reaches far beyond the chalkboard where it is represented in a series of boxes, arrows, numbers and letters. She serves as Branch Manager for the Library and Archives System Support Branch of the Office of the Chief Information Officer.

Ching-hsien explains how an old-fashioned chalkboard helps her organize the complex systems she oversees for the Office of the Chief Information Officer. (Photo by Amy Rogers Nazarov)

Among the projects in her wheelhouse is the Collections Search Center, which allows anyone to search all of the Smithsonian’s collections. It has drawn broad acclaim for being the first system to offer users a way to search museum, archives and library records in a single place.

The Collections Search Center is backed by the Enterprise Digital Asset Network (EDAN), where more than 10 million object records are aggregated from 50 major collection databases across the Smithsonian. At least 25 Smithsonian websites use EDAN as their primary data repository. When the public interacts with the Institution’s home page or any of those 25 websites, they are in fact pulling data from EDAN.

That’s notable because data from art, history or bio-science disciplines use different classification systems. Moreover, libraries, archives and museums have their own terminology, data formatting and standards. Wang’s team’s task was to make different data behave similarly during a search.

The complex work involved establishing a Smithsonian standard data model that could support a multitude of different classification systems and data formats. Under Wang’s leadership, the team also created hundreds of custom computer programs to “massage” the data to conform to that data model. The result of these efforts were critical to the success of the institution-wide collaborations.

Then there’s the Transcription Center, which is an online platform that invites digital volunteers around the world to transcribe and review items such as letters, diaries, manuscripts, museum objects and specimens. So far, more than 318,000 pages have been transcribed by roughly 10,000 volunteers. Wang’s team turns the transcribed contents into searchable content.

Transcription Center volunteers painstakingly transcribed the tiny labels affixed to the thousands of bumble bees in the Smithsonian’s entomology collection. Photo by John Gibbons)

Volunteers love the work, she says. “They find the material interesting and the process satisfying. They are helping us unearth what we call ‘the hidden collections.’”

Also under Wang’s purview is the Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives (SOVA), which allows researchers to search collections of archival materials from dozens of archives across the Institution. In this endeavor, the team worked closely with archivists to provide technical support that would ensure archival contents are catalogued in the computer system for internal management, as well as for public searching and display.

“I have a fantastic team working with me,” Wang says. “It took years and years to be able to develop all of this.”

The groundwork for Wang’s career in IT was laid long ago in China, where she grew up in a family of professors–and where her schooling was interrupted in third grade by the Cultural Revolution.

Overnight, school–once a place of order and discipline–become chaos. “We would just wander around the campus, listening to [political slogans] coming out of loudspeakers,” she recalls. Thousands of schools and universities were soon closed, and Wang’s parents and grandparents, along with other “intellectuals,” were forced by the Communist government to work in labor camps. The family’s possessions–old photographs, the piano Wang loved to play–were taken or destroyed by the marauding Red Guards, who would show up unannounced and search private homes for evidence that a household had been “infected” by capitalist thought.

“You had to keep your head down” during these years, says Wang, who didn’t go back to school until she was a teenager. “It sort of toughened me up.”

Years later, when Wang was working at Beijing University in her government-assigned job (making punch-tape-machines for use with computer tapes), a classmate announced he was leaving for college in Japan. When Wang mentioned the news to her father, he surprised her by telling her she too could go abroad to study–and that she could live with relatives in the US. Until that moment, she didn’t even know she had family in the States.

Just three months later, she arrived at what was then known as National Airport on a frigid day in January 1979. “It was unreal. I was pinching myself for days.” She set a goal of learning 100 new words in English per week, and soon enrolled in Montgomery College and later, the University of Maryland, from which she graduated in 1982 with a bachelor’s degree in computer science.

Almost 30 years supporting the “increase and diffusion of knowledge” via technology is a point of pride for Wang. She has devoted her energy and expertise to helping Smithsonian staff improve quality of their work, as well as increasing the accessibility of Smithsonian collections to the public.

“I know for a fact that what I do have a positive impact on users,” Wang says. “That gives meaning to what I do here every day.”

Posted: 6 October 2017

- Categories: