ICYMI: Highlights from the week that was Dec. 3 – Dec. 9, 2017

No one can keep up with everything, so let us do it for you. We’ll gather the top Smithsonian stories from across the country and around the world each week so you’ll never be at a loss for conversation around the water cooler.

This week, our scientists second-guessed Einstein, caught the North Koreans in a fake-out and proved once and for all that naked mole rats are THE MOST ADORABLE. Really, who wouldn’t love that little face?

A Year Later, The Smithsonian’s African American History And Culture Museum Faces A Different World

WAMU, The Kojo Nnamdi Show, December 4

Founding Director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture Lonnie G. Bunch III welcomes the audience to a screening of the film “Hidden Figures” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Wednesday, Dec. 14, 2016 in Washington DC. Photo Credit: (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

Last October, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened its doors, the result of decades of planning. Since then, nearly three million tourists and locals who have been lucky enough to snag the notoriously hard-to-come-by tickets have visited. Local and national conversations around race and politics have also evolved dramatically since the museum’s opening. As 2017 comes to a close, the museum’s founding director joins Kojo to discuss the museum’s first year and its shifting role in local D.C. Listen to Kojo Nnamdi’s interview with Lonnie Bunch for WAMU.

Maybe Einstein Was Wrong About This

A new analysis suggests an oft-cited claim about when astronomers peak is pretty off.

The Atlantic, December 4

Of the many catchy quotes attributed to Albert Einstein, this may produce perhaps the most anxiety among the scientists who have come after him: “A person who has not made his great contribution to science before the age of 30 will never do so.”

The exact origins of the oft-cited statement are murky, so it’s difficult to determine whether the great theoretical physicist said it in seriousness or jest. Whatever the intention, research on the connections between age and scientific output have frequently shown that Einstein’s claim was wrong—or at least, not exactly true for everyone. The study of these connections is far from new, and the results are usually tricky to extrapolate to larger populations. An effect found for top performers in one field may not necessarily apply for high achievers in another, for example. But the topic has long fascinated researchers and writers, including Helmut Abt, an astronomer and former longtime editor at The Astrophysical Journal. Read more from Marina Koren for The Atlantic.

North Korea Probably Tampered With Its Missile Launch Pictures

Newsweek, December 5

North Korea has tampered with the photos showing the latest missile test launch, an analyst said after inspecting the images the regime released last week.

According to Dr Marco Langbroek, Space Situational Awareness consultant at Leiden University in the Netherlands, the stars in some of North Korea’s images don’t match, suggesting the regime tampered with the photos before publication. He found that two images that were shot from the same viewpoint seeme to display different constellations.

“Two images from clearly same viewpoint, but dramatically different star backgrounds! Orion (Southeast) versus Andromeda (Northwest)!” the scientist wrote on Twitter on Tuesday. Read more from Sofia Lotto Persio for Newsweek.

American laborers as art at the National Portrait Gallery

NPR’s “Marketplace,” December 5

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., has a new exhibition called “The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers.” It’s combination of art and history, and the realities of some of the people who’ve helped make this economy go from the 18th century to present day.

Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal got a walking tour with the museum’s curator of painting and sculpture, Dorothy Moss.

Dorothy Moss: The title came from our senior historian, who is the co-curator of this exhibition, David Ward. He wanted to reflect back on the time when men were doomed to work, in the sweat of their face, and women were asked to raise the children. And going back to that ethic, that work ethic, that came from the biblical times and became sort of the Protestant work-ethic of this country. Read more of Kai Ryssdal’s interview on Marketplace.

An archaeological dig unearths one of the earliest slave remains in Delaware

The Washington Post, December 5

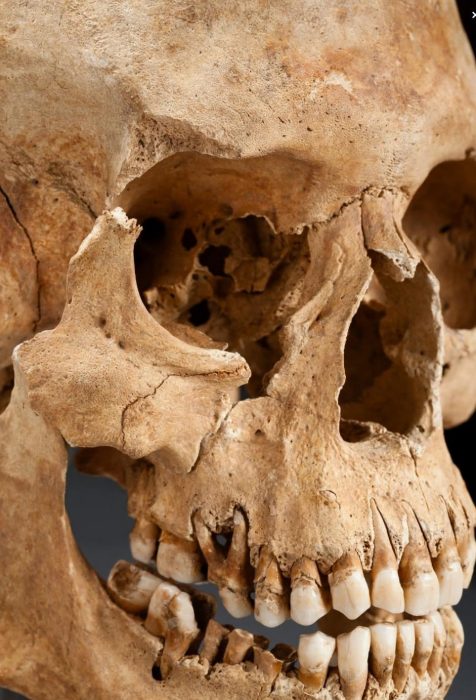

A male skeleton of African ancestry was found at Avery’s Rest, a late 17th-century plantation in Rehobeth, Del. (Photo by Kate D. Sherwood / Smithsonian Institution)

The blow to the head of the man in grave 10 was so severe that it chipped off a bone near his right eyebrow, fractured part of his face, and probably helped to kill him.

He was about 35 years old and likely a slave. He had grooves in his front teeth where he had clenched his clay pipe as he worked, and evidence in his spine that he was engaged in hard labor.

It’s not known exactly what landed him in a hexagonal coffin in the sandy soil north of Delaware’s Rehoboth Bay 300 years ago: An assault, or an accident?

But fragments of his story, along with those of 10 others buried near him, have emerged from an archaeological dig at a long-vanished 17th-century plantation called Avery’s Rest in Sussex County. Read more from Michael Ruane for The Washington Post.

This painting might be sexually disturbing. But that’s no reason to take it out of a museum. (Perspective)

The Washington Post, December 5

Visitors pass by Balthaus’s “Therese Dreaming” at Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany in 2007 (Photo by Oliver Berg)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has made the right decision, to reject the demands of an online petition calling for the removal of an erotically charged work by the Polish French artist Balthus. The 1938 painting, “Thérèse Dreaming,” shows an adolescent girl sitting on a chair, with one leg raised to expose her undergarments. The petition, which has gained more than 9,000 signatures, argues that the painting “romanticizes the sexualization of a child.”

There is a difficult and emotional conversation to be had about Balthus’s works, which frequently depicted adolescent or pubescent girls in a sexualized way. No serious exhibition of Balthus, who died in 2001, can avoid confronting those issues. But the petition goes wrong when it argues that the painting should be removed from view now because of the larger and still unfolding scandals of sexual abuse in the media, entertainment, arts and political worlds. Now is precisely not the time to start removing art from walls, books from shelves, music from the radio or films from distribution. The focus should be on the social structures that perpetuate abuse and the people, mostly men, who commit it. Read more from Philip Kennicott for The Washington Post.

Pocket-size rodent attracts big fan base and $41,000 in donations to National Zoo

WJLA, December 5

They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Or in this case, maybe beauty is only skin deep. In just a few weeks, the National Zoo has collected tens of thousands of dollars to build its naked mole-rats a new home.

In case you missed it, these blind, mostly hairless rodents from east Africa have a big fan-base at the zoo. It’s enough to make even the pandas jealous.

These creepy-looking little critters live their entire lives underground in places like Somalia and Ethiopia.

“Because it’s hot and humid underground in Africa, they have not a lot of hair on their body,” said Kenton Kerns, assistant curator of the Small Mammal House at the National Zoo. Read more and watch the full story from Mike Carter-Conneen for WJLA.

Inside the Smithsonian’s plan to reach 1 billion people by 2022

Axios, December 7

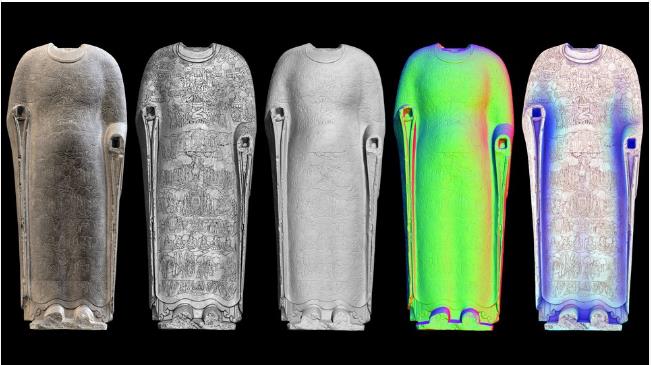

The Smithsonian has set a new goal of reaching 1 billion people, both in the U.S. and abroad, by 2022. The core of the plan, according to Secretary of the Smithsonian David Skorton, is to bring the museum’s collections to those who physically can’t visit by digitizing more than 15 million items and making them available online.

Why it matters: Skorton told Axios that their efforts are not only about expanding reach, but also about “convening conversations on topics where the country is struggling and where we have some expertise.” Read more of Alyana Treen’s interview with Secretary Skorton for Axios.

Herbarium Explorations

Much more than collections of dead plants and fungi, herbaria are irreplaceable repositories of historical plant information vital to a wide variety of scientific applications.

The American Gardener, December 8

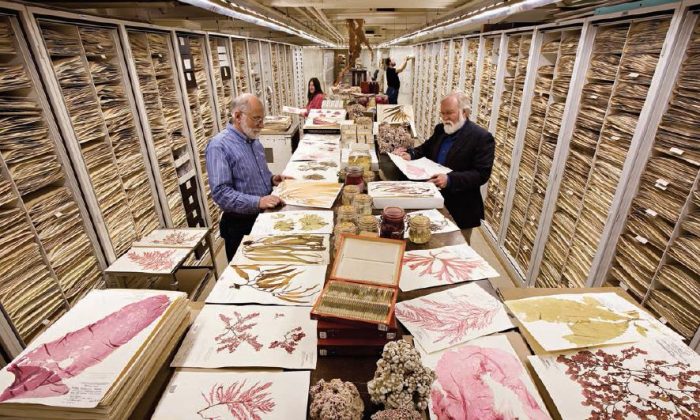

In the U.S. National Herbarium at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, botany department staff examine pressed and jarred specimens of algae. (NMNH)

It’s easy to be amazed and inspired by the vibrant, living collections of plants at public gardens and universities. But there are 400,000 species of plants and possibly millions of species of fungi on the planet—far more than all the public gardens in the world can display. The job of maintaining historical records of all those plants and fungi goes on largely out of public view, in archives known as herbaria.

“Herbaria serve as an encyclopedia of the Earth’s flora,” says Vicki Funk, Senior Research Botanist & Curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C. “They are really our only record of what’s been on the planet in the past, what’s here in the present, and what we predict into the future,” she adds. Yet many people don’t fully understand why herbaria are important. “There’s a misconception that the collections are just a bunch of boring dead plants, and that what we do is not science,” Funk says. “In reality, it’s not that at all. We collect specific things to answer specific questions.” Read more from Marcia G. Yerman for The American Gardener.

Posted: 12 December 2017